Private summer schools prompt debate on education inequality

- Share via

In Beverly Hills, high school students can take a U.S. history course for $798 this summer; in La Cañada Flintridge, Spanish is offered for $775, and in Arcadia, a creative writing course costs $605, plus a $25 registration fee.

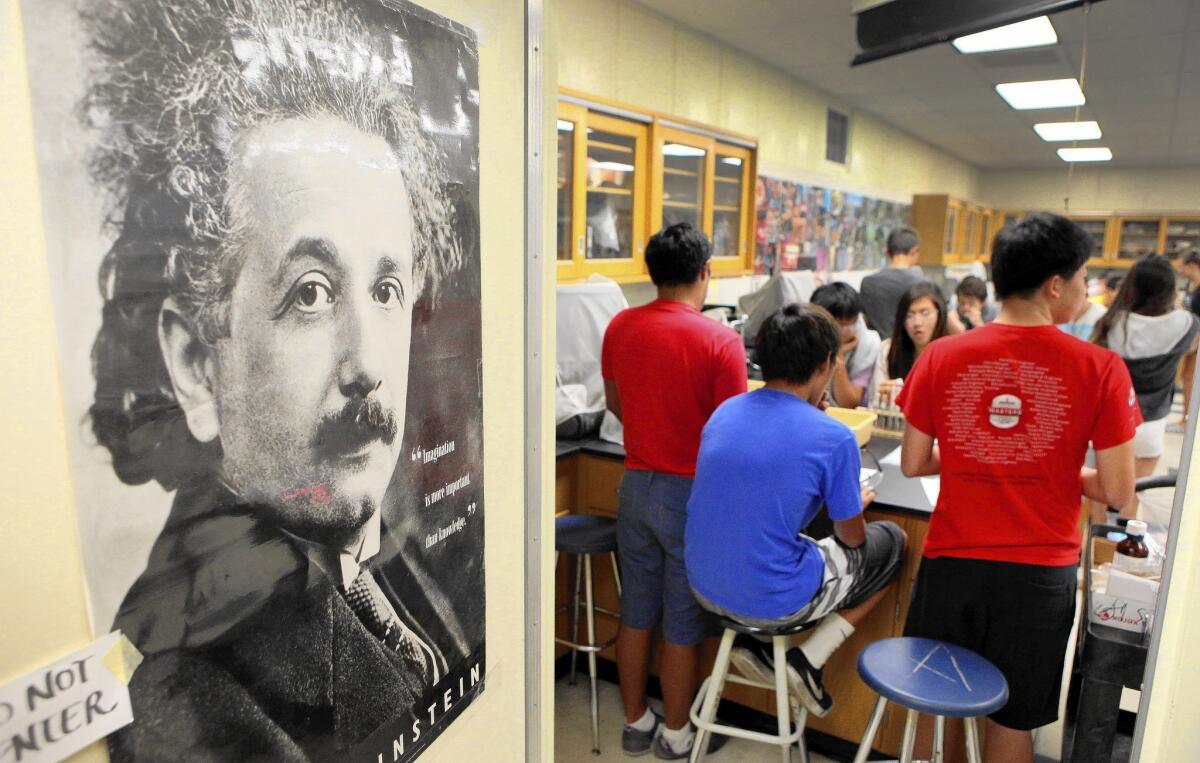

While summer programs in many California public school districts have been scaled back or eliminated, scores of students in predominantly affluent areas can pay for courses, bolstering their transcripts to be more attractive to colleges.

The classes, which have gained popularity in recent years, are offered by nonprofit foundations on leased high school campuses. They often are taught by district instructors and run by administrators hired by these groups.

The foundations carefully structure their programs to sidestep state law that bars public schools from charging for educational activities, by remaining independent of the school district.

Critics say the foundations, though well-intentioned, privatize public school, undercut California’s guarantee of a free public education for all and contribute to an already wide inequity in educational opportunity by offering public school credit at a cost only some can afford.

“What about the kids whose parents can’t create a foundation and pour money into it?” said Cal State Fullerton political science professor Sarah A. Hill, who studies public education finance. “They say, ‘We just care about our kid’s education’ and you can understand that, but so do poor parents — they just don’t have the resources to pay for summer school.”

Jinny Dalbeck, who oversees the La Cañada summer program, said because the La Cañada Unified School District has cut summer school, her group is filling the void.

Students enroll for a variety of reasons: some seek to get a head start on the coming school year, or clear up space for more advanced courses, and others want to retake classes for a better grade, Dalbeck said.

“It’s truly a stand-alone, private school for five weeks,” Dalbeck said. “We’re not a public school. We’re meeting a need that the students have — to be able to work ahead.”

About 675 local education foundations operate in the state, according to the California Consortium of Education Foundations. The groups raise money from parents as well as some local businesses with the express purpose of addressing shortfalls in state funding.

They have become a crucial fundraising arm for some schools, donating tens of millions of dollars each year.

A review of tax documents by Hill and others found that some of the more affluent groups provide campuses with thousands of dollars per student in addition to state per-pupil funding.

In 2011, the Manhattan Beach Education Foundation’s total revenue was nearly $7.5 million; the Hillsborough Schools Foundation, which supports a 1,500-student elementary school district in the Bay Area, brought in about $4.2 million.

When local districts are most in need, the foundations spring into action.

The groups have saved or brought back services and programs such as music and art that were cut during steep budget shortfalls in recent years.

During those lean times, some school officials attempted to maintain programs and activities by charging students for such things as workbooks and extracurricular activities. Some districts provided summer school — for a price.

The ACLU sued the state in 2010 over these costs, but dropped the case two years later after a law was passed requiring the state Department of Education to ensure that schools don’t charge illegal fees. The law also created a complaint process to challenge possible violations.

As a result, the foundations began offering classes on their own.

Dozens of complaints have been filed around the state in the past year by parents and others who contend districts are essentially outsourcing summer school, dictating class offerings and in effect charging students for credit.

The state has not found a school district or foundation in violation of the law.

The foundations contend that while there is communication with the local district, they remain separate entities.

“They’re a public school and we’re a fee-based school program,” said Andrea Sala, executive director of the Peninsula Education Foundation. “They don’t have any say in our curriculum — though it’s the same curriculum because it’s the same teacher — we run it independently.”

David Sapp, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union, said the state must ensure that districts aren’t complicit in offering education programming for a fee.

“That would explicitly conflict with the free-schools guarantee,” he said.

It is a line that can be easily crossed, said Claremont attorney Ronald T. Vera, who advises foundations.

Vera said he has declined to work with organizations that did not legally operate their programs. In one case, he said a district paid teachers to work in the foundation’s summer school. He counsels groups who charge fees to be aware of the law and to maintain a distinct division.

“It’s murky waters,” he said.

Caroline Kim, 14, is taking biology at the Peninsula High campus in Rolling Hills Estates for $670 to get a head start on her sophomore year. In the fall, she plans to take physics. Caroline and about 1,200 of her peers are attending classes offered by the Peninsula Education Foundation.

The cost wasn’t an issue for her family and it is well worth the price, she said.

“I’m really lucky to be in this school district and have this opportunity,” Caroline said. “Summer school allows me to take advantage of all these opportunities and I’ll be a lot more prepared for college.”

Many summer programs are not approved by the Western Assn. of Schools and Colleges, which accredits public and private high schools in California. For credits to be placed on a student transcript, a principal must approve them.

High school students have long taken community college courses — at a cost of $46 per unit — and they also can take online courses to fulfill graduation requirements.

Many districts, such as Los Angeles Unified, have had little to no support from these types of foundations.

In 2007, the nation’s second-largest system had a budget of about $40 million to offer summer classes at all levels, said Javier Sandoval, an administrator with the district’s Beyond the Bell program, which coordinates after-school and summer programs.

Last year, funding plummeted to about $1 million and L.A. Unified could accommodate only about 6,000 high school students who needed credits to graduate. This year, the district is offering classes to about 36,000 students; about 198,000 high school students are enrolled in L.A. Unified.

Sandoval said families of students in L.A. Unified, nearly 80% of whom are considered low-income, are at a competitive disadvantage to their peers elsewhere.

“Those who have money can have their students go to summer school, and those who can’t are stuck,” he said. “It sets up an inequitable system.”

The cost can be high even for some families in these more affluent areas, said Ronit Stone, president of the Beverly Hills Education Foundation. Some foundations offer scholarships.

“Nobody is required to take summer school,” she said.

stephen.ceasar@latimes.com

Twitter: @stephenceasar

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.