Great Read: A Central Valley high school goes Bollywood

- Share via

Reporting From Fowler, Calif. — Luckily, Shandeep Dhillon’s cousin had recently gotten married.

That meant he alone could outfit much of Fowler High School for its first Bollywood night. His uncle’s regal, embroidered sherwani coat went to the Central Valley school’s principal, Hank Gutierrez. The outfit Shandeep, 13, had worn but outgrew went to Gutierrez’s son Jordan, and Shandheep wore another cousin’s, on down the line of his extended family’s wedding clothes.

The Punjabi girls at school all had salvar kameez outfits they could lend to their Latina, Armenian and Swedish classmates.

“We go to lots and lots of Indian weddings and you dress up and feel like a princess,” said Manpreet Shaliwal, 16, in silky, peacock blue.

Even girls she had never talked to before had been introducing themselves over the last month, hoping to borrow one of her colorful outfits.

The cafeteria’s ceiling was transformed by a parachute of tulle. That Pinterest vision had cost more than $200. But Harcoover Singh Bhatti, the Punjabi club president, argued that it would be worth it for the gasps now being emitted as students entered.

More students than he had dared expect bought $10 tickets to the dance. The 18-year-old ran about in a happy panic checking the supply of samosas.

“This was three years in the making. Three years!” he shouted as he sped past in his usual black turban. “It’s a first!”

Gutierrez, wearing sparkling slippers that curled up at the toes, watched the barely contained chaos.

“This is it,” he said. “This is my favorite moment of being principal. I grew up in this small town. The son of a single mother. I wanted this school to have what she gave me — a sense that we’re family and it’s not about what the outside world says, but what we create.”

::

The outside world says it’s tough to be a Sikh kid.

A study by independent researchers, presented to Congress last month by the Sikh Coalition, found that Sikh children in Central California face some of the highest rates of bullying in the country.

Fifty-four percent of students ages 12 to 18 reported harassment. For turbaned youth it was 67% — more than double the national average for bullying. Strictly observant Sikhs don’t cut any hair, believing that everything about a person’s body is sacred. Men and boys often wear their long hair wrapped in turbans.

The report’s findings were unsettling in a place where turbans are as common in the trucking and farming industries as a John Deere cap. Gurdwaras — Sikh temples with their colorful flags — rise at regular intervals amid grape fields and farm towns, always open to anyone and serving free meals. Sikhs have lived in the San Joaquin Valley for more than 100 years, and it’s home to more than 30,000 Punjabi. (Sikh is the religion and Punjab the region of India where many Sikhs come from.)

“People saw us differently after 9/11,” said Simran Kaur, a graduate nursing student serving food at the Nanaksar Sikh temple in south Fresno.

Although many of the interviews included in the Sikh Council report were conducted here, Kaur said she was surprised at the findings.

But perhaps students revealed in interviews what they didn’t want to admit to themselves.

Kaur said she’s never experienced bullying or harassment.

She decided to adapt to American culture. Her eyebrows are gracefully plucked. There are layers cut in her long hair. But she’s proud of her husband for not bowing to norms. He wears a turban, but he hasn’t experienced abuse either, she said.

Well, sometimes at the convenience store where he works, men call him a terrorist, but he just shrugs it off, she said. And there was that time some men tried to run them off the road near Sacramento, but they were shouting “Muslims.”

“We’re not Muslim. So in a way it could have been anyone,” she said. “We don’t like to think of ourselves as being targeted.”

::

Bhatti, the force behind the Bollywood dance, was born in America — a circumstance that caused his mother great worry even before it took place.

She came to the United States as an arranged bride and was alarmed by American children.

“She said they were all brats. She wanted her first child to go to India and learn respect for elders and our culture,” he said.

At age 6, his parents sent him to a boarding school in the Himalayas. There was one letter a month from home, and a weekly five-minute phone call. (“I could hear the pain in my mother’s voice.”) There were pressed white school shirts and white sheets and white towels. Everything kept neatly in a trunk.

“I cried my eyes out the whole first year,” he said. “It was just like Harry Potter, but without the magic.”

When Bhatti came home to go to high school in Fowler, a town of 6,000 about five miles south of Fresno, he had studied English grammar and passed a written test into an honors English class but he couldn’t speak or understand it.

He asked his parents for a tutor. When they told him they couldn’t afford one, it was the first time he realized that they had little money. His mom worked in a raisin-packing house, his father on the line of a nut-manufacturing plant. They had sent him to school through sacrifice.

Over the summer he taught himself English. The next summer he learned to swim. The swim team was largely white, and he wanted to do the thing people least expected a Punjabi student to do. He made the team.

The next year he joined the drama club. He thought people didn’t expect a turban-wearing student to be in theater. He’s been accepted at a string of big-name universities. He plans to go to medical school someday.

At the end of his junior year, he was volunteering at a Fresno hospital when they brought in Piara Singh, an 82-year-old Sikh man who had been beaten with a steel pipe outside a temple in what police said was a hate crime.

Bhatti talked with Singh, universally known as baba-ji — Punjabi for grandfather. The older man told him he hadn’t thought anything like that could happen in the Central Valley. He was only out for his morning walk, the same walk he had taken for years.

His senior year, Bhatti became president of the Punjabi club and vowed to make the dance that they’d talked about for years happen at the school, where 51 of the 680 students are Punjabi.

Some of the Sikh boys were the biggest naysayers.

“They said it was going to be lame because they worried people would make fun of it,” Bhatti said.

“I kept quiet,” he said. “But I knew it was going to be epic.”

::

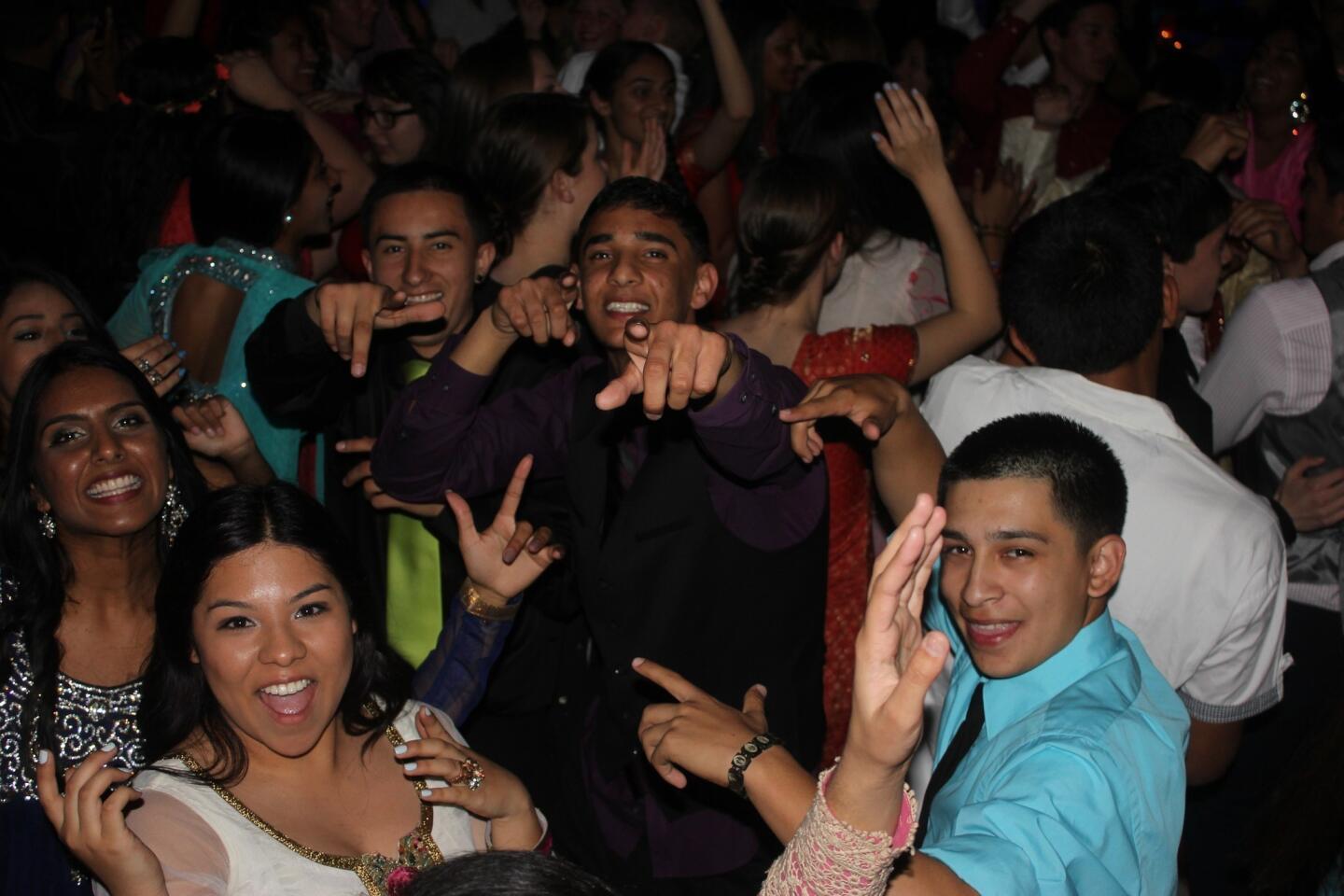

The night of the event, after the dishes were cleared and a Sikh dance troupe took the floor to perform, those boys and Bhatti’s friends from the swim team packed themselves against the back wall of the cafeteria.

The costumed dancers drummed their feet and swirled. Students took photos and clapped along. The boys at the back, beneath a “Go Redcats!” sign, threw their heads back and whooped. They thumped Bhatti on the shoulders.

When the performances ended, DJ Malhi, who usually works Indian weddings, dimmed the lights and pumped Jazzy B, a Punjabi singer called the Crown Prince of Bhangra, a mash-up of traditional Punjabi music, hip-hop, house and reggae.

The thunderous rush to the dance floor was immediate. There was no prodding or coaxing. Somehow the boys from the back got there first, Bhatti’s black turban bopping up and down in the middle of them.

“When I saw people running to the dance floor, I knew the only thing left to do was have fun,” he said.

Chandler Collins, 17, waved hands covered with henna tattoos. Bhatti’s blond best friend from the swim team, Caleb Savoia, pogoed into the circles of girls dancing together. The only one dancing with more enthusiasm was Harjinder (J.J.) Kalirai, a tall, quiet boy who wears a turban. A circle cleared around him and students clapped in time.

While they danced, teacher Anika Arya, the Punjabi club’s faculty advisor, sneaked off to a corner and cried.

She wasn’t sure why, she said, but it was something about seeing a shy Sikh boy who usually walked with his head down, joyfully dancing as classmates cheered him on.

Twitter: @DianaMarcum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.