Sharing lessons forged in the Cedar fire

- Share via

LAKESIDE, CALIF. — As firefighters battled flames and evacuated northeastern San Diego County in October, a group of Cedar fire survivors did what they wished someone had done for them five years ago.

They headed out on fire watch.

David Kassel, 53, the group’s founder, drove over to Billi-Jo Swanson’s horse ranch with his fire hose to help wet down brush.

Steven Murray, 54, rode his motorcycle above San Vicente Dam to investigate reports of flames climbing the hill.

Then Kassel and Valentine “Val” Lance, 67, motored out to keep tabs on Wildcat Canyon Road, a major thoroughfare to Ramona that firefighters kept closing. The pair advised residents whether to stay home or evacuate.

That kind of expertise was hard won. Five years ago, they met as shell-shocked strangers, burned out by the Cedar fire -- the state’s worst in 75 years -- which consumed 273,000 acres, killed 15 people and left more than 3,000 homeless.

Survivors convened on Thursday nights in the Lakeside storefront of Maine Avenue Tax Service. They were academics and ranchers, Democrats and Republicans, exurban neighbors who wouldn’t have said more than hello at Starbucks before the fire.

Week by week, they helped each other through illnesses and other crises. The group grew from 10 to 50, adding an online list of many more. Some rebuilt bigger and better, and dropped out of the group. Others faltered and still haven’t rebuilt.

Then the wildfires returned to San Diego County. New fire victims began turning up at meetings, adrift and alone, and the dozen remaining regulars realized that they had a new mission.

At one of the Cedar fire group’s first meetings, a dozen survivors sat in a circle and took turns telling their stories.

Kassel, a branch manager for a gate company, sat with his wife, Kathy, 50. White-haired Alma Russell, 66, came with partner Alvin Minnick, 70. Debbie Williams, 47, brought her two kids. Lance, a retired British biologist, had his golden retriever Camillo at his feet.

Russell cried as she told about her tenant of 10 years who rescued a neighbor, then became trapped by the flames and returned to her bed to die.

At a later meeting, Lance told the group how four of his neighbors died trying to flee the fire, including a man stranded in an RV with his Irish wolfhounds.

A few meetings later, Kassel asked the group if they wanted to talk about their emotions. They said no. They weren’t ready.

He never asked again.

“People talk about not so much their feelings as the situation they’re in,” Kassel said. “You don’t have to say ‘I feel this way.’ We know.”

In those early days, the group was overcome by a numbness that Minnick described as “doubled-over painful.”

They were lonely. Family and friends were sick of hearing them complain about dealing with trash haulers, county permits and insurance.

They were weighed down with binders of paperwork, straining to remember how many electrical outlets they lost in the fire, how many light fixtures and drawers full of -- they couldn’t remember just what, but surely something they would miss in a year or two.

Some didn’t have insurance, or discovered soon after the fire that they were underinsured. They couldn’t afford to rebuild. Others weren’t sure they wanted to.

Together, they found their way.

Swanson, 63, the rancher, needed to rebuild for her 26 quarter horses, but she didn’t have insurance on the little adobe house her parents built in the 1920s, and she didn’t want charity.

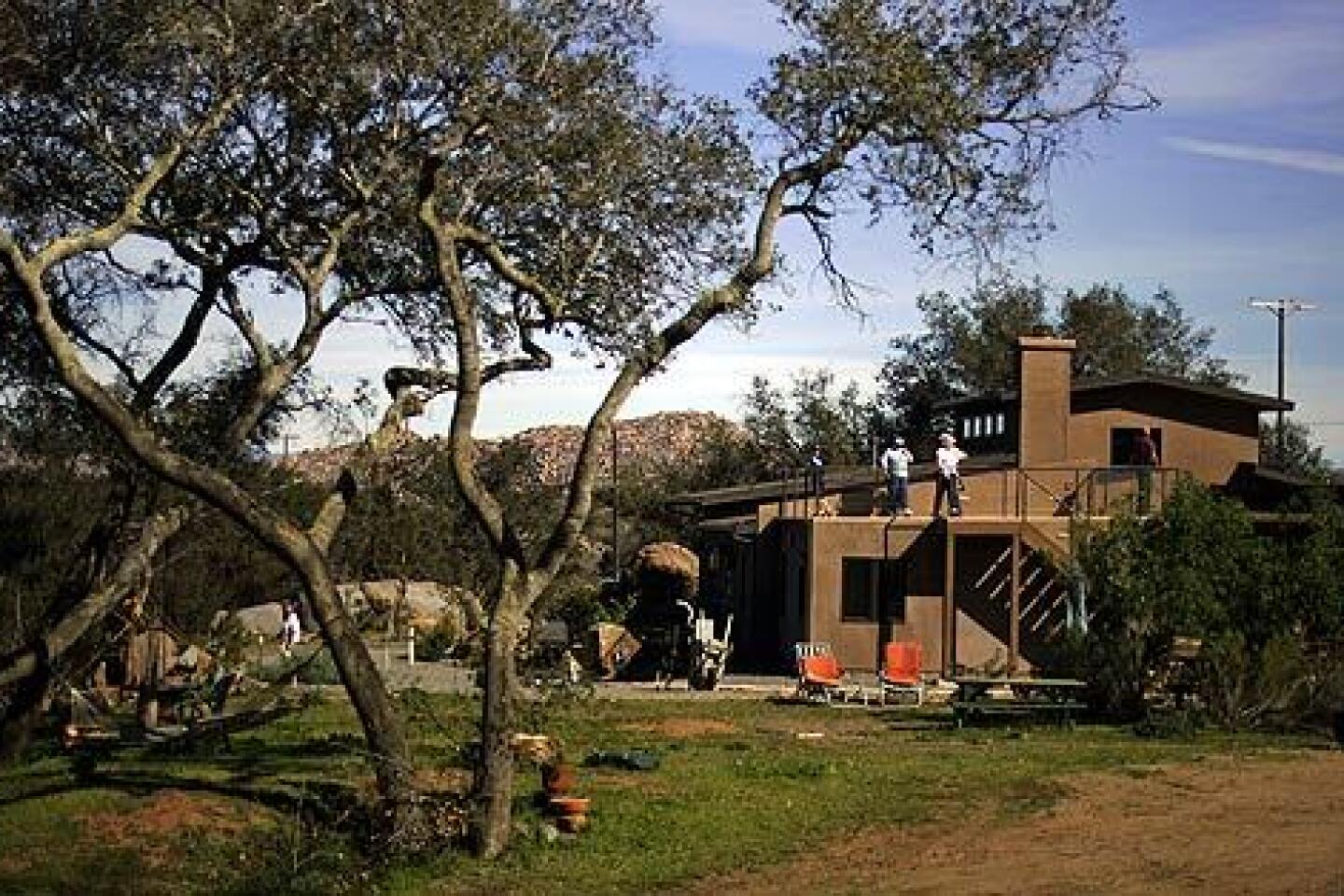

Kassel’s wife, Kathy, and other members of the group persuaded Swanson to accept the assistance of a group of Christian volunteers, who helped her build a new house about two years ago.

After Minnick’s kidneys failed last year, Lance and others kept working on his house until he was healthy enough to return.

When another group member’s wife fell, hit her head and was hospitalized, Kassel and others took turns ferrying him to the hospital and to meetings.

And when an evacuation order was issued for Lance’s neighborhood during the recent fires, Kassel called.

“Have you found a place to stay?” Kassel asked.

No, Lance said, he hadn’t.

“Well you should come stay with me,” Kassel said.

And that’s how Lance ended up surviving his latest evacuation -- in the spare bedroom of Kassel’s newly rebuilt home.

The Cedar fire group has its own rules for judging when someone’s finished with “the rebuild.”

Only after San Diego County building inspectors issue their final approval does the group celebrate. They even have a term for it: “getting final.”

The Kassels are done. Williams is close -- she just needs to plant some landscaping. But Jim Robinson, 66, is another story.

The retired Caltrans surveyor attends all the Cedar fire group meetings, stays for dinner and gathers construction tips.

Robinson stays at his late mother’s home in Springdale, and drives over to the site of his burned-out, one-bedroom ranch house in Lakeside twice weekly to water the gardens and clear the slab.

He has no desire to build a grand home like the Kassels. He loved his modest ranch house, built in 1959, bought in 1980.

He carries pieces of the house with him, bracelets fashioned from warped copper wires he cut from the ruins.

Robinson has received his insurance settlement, but says he often feels too old to handle such a big project, even with the group’s support.

The closest he’s come is drawing a picture of his ideal house on the computer, a picture that, if not for a slightly steeper roof and two dormer windows tacked on top, looks just like his former home.

Kassel, the Cedar fire group leader, recently invited Robinson over, hoping to inspire him to rebuild.

The pair walked up the driveway of iridescent peacock slate, past solar-powered lanterns and white oleander to a front door flanked by copper fountains. Once inside, they passed walls of family photos the Kassels received from relatives to replace those lost in the fire.

Kassel pointed to the melted remains of his son’s jet ski, which he mounted on the wall of his first-floor office as a reminder of the fire.

Robinson asked about the recessed lighting that sent a warm glow across the vaulted ceilings and exposed orange beams. Kassel showed Robinson the kitchen mini bar with its built-in wine rack and the master bath, whose shower boasts so many jets it looks like it belongs on “Star Trek.”

Robinson says he’s made a decision: “I’ve decided I want to use big tile instead of small tile” in the new house.

It’s not a commitment to rebuild, Kassel says later, but it’s a start.

To help the latest fire survivors, Kassel drove out to Ramona in November to organize a new group.

During a meeting at the town’s Lutheran church, about 60 people described in raw, bitter voices how they had been battling Federal Emergency Management Agency bureaucrats and two-faced insurance adjusters.

Many were impatient, demanding solutions, rather than presentations titled “How do I determine my loss?”

“I didn’t even need to come,” said one middle-aged blond woman as she stormed out early.

Kassel says it reminds him of the Cedar fire group in the early days -- still in shock, isolated and grieving.

But some of those filing out of the church at the end of the meeting thank him, including John and Ginny Vehar, both 55, who lost their home in the Ramona blaze. They say the Cedar fire survivors have given them hope.

Williams is telling her story again, the one about architects losing the plans for her new house.

It’s a familiar tale around the long pine table at Lakeside Steakhouse, frequent site of Cedar fire post-meeting dinners.

But it’s a new story for the Vehars, who put down their drinks and listened close.

Williams’ first architect blamed his courier for losing the plans.

The second, recommended by a trusted “fire family,” seemed a “very honest, Christian man” until he lost the plans, fell into a deep depression and hid from her. She’s now on her third architect.

“So how many times did they lose your plans?” Kassel shouts as people joke about Williams getting a LoJack or GPS for her blueprints.

The new couple from Ramona consider. Rebuilding, they say, sounds like a full-time job.

It is, Williams says.

She and Kathy Kassel start debating whether they’re better off for having lost everything.

“In a way, you hate to say it, but it’s very freeing,” Kathy Kassel said, “Not to have all this clutter, all this stuff.”

“All those skinny clothes I was going to get into,” said Williams, a pixieish blond, “Poof! It’s gone.”

In December, David Kassel asked Williams to mentor a woman whose house recently burned in nearby Jamul. Williams arranged for them to meet at a local Starbucks.

They talked all morning. Turned out, the new fire survivor, Anne Gurnee, 37, also was a mother, had insurance and wanted to rebuild. Gurnee also worried, the way Williams once did, about all she had lost.

Williams knew it was too early to tell Gurnee what she’s facing, what it’s like to realize, as Christmas approaches, that all your ornaments are gone. How celebrating in a trailer two years running can feel like a chore, stumbling over the kids, fetching dress clothes from a storage container outside plagued by rats.

But there are good things, too, almost as difficult to articulate. For instance, how a group of strangers can displace a circle of PTA friends, shifting your focus from damaged keepsakes to the fate of the group.

Dozens packed into Williams’ rebuilt kitchen two weeks ago Sunday passing plastic cups of champagne across the brown quartz counters and straining to hear her tell the story of the chocolate cake.

They had gathered for the annual Cedar fire home tour that morning, new and old fire survivors piling onto a bus to travel from Kassel’s house to Lance’s and eight others in various states of construction.

There were the Vehars, taking notes for their binder.

There was Anne Gurnee, Williams’ mentee, trying to take it all in, blinking back tears at the sight of all the work ahead of her.

“I can’t quite control myself yet,” she said. “Another few months . . .”

And there was Williams, telling the story of the cake.

The night before the Cedar fire, Williams said, she had baked a chocolate cake. The next morning, as the family fled, no one thought to grab the cake.

“What they got was the ‘South Beach Diet’ book and what I really needed was chocolate,” Williams said.

After the fire, living in a trailer and shopping at Costco, Williams would eye the deluxe chocolate cakes -- another reminder of her old life -- and wonder when she would have enough room to throw a party again.

Three years later, still in the midst of rebuilding, Williams bought her first post-fire chocolate cake -- for a Cedar fire group meeting.

Last week, with her house almost finished, Williams bought her second cake, in honor of new fire survivors on the home tour.

After serving up slices and pouring champagne, Williams raised her glass in a hopeful toast.

“To everybody who is rebuilding your home,” she said, “Have faith.”

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.