Some chafe at downtown L.A.’s business improvement districts

- Share via

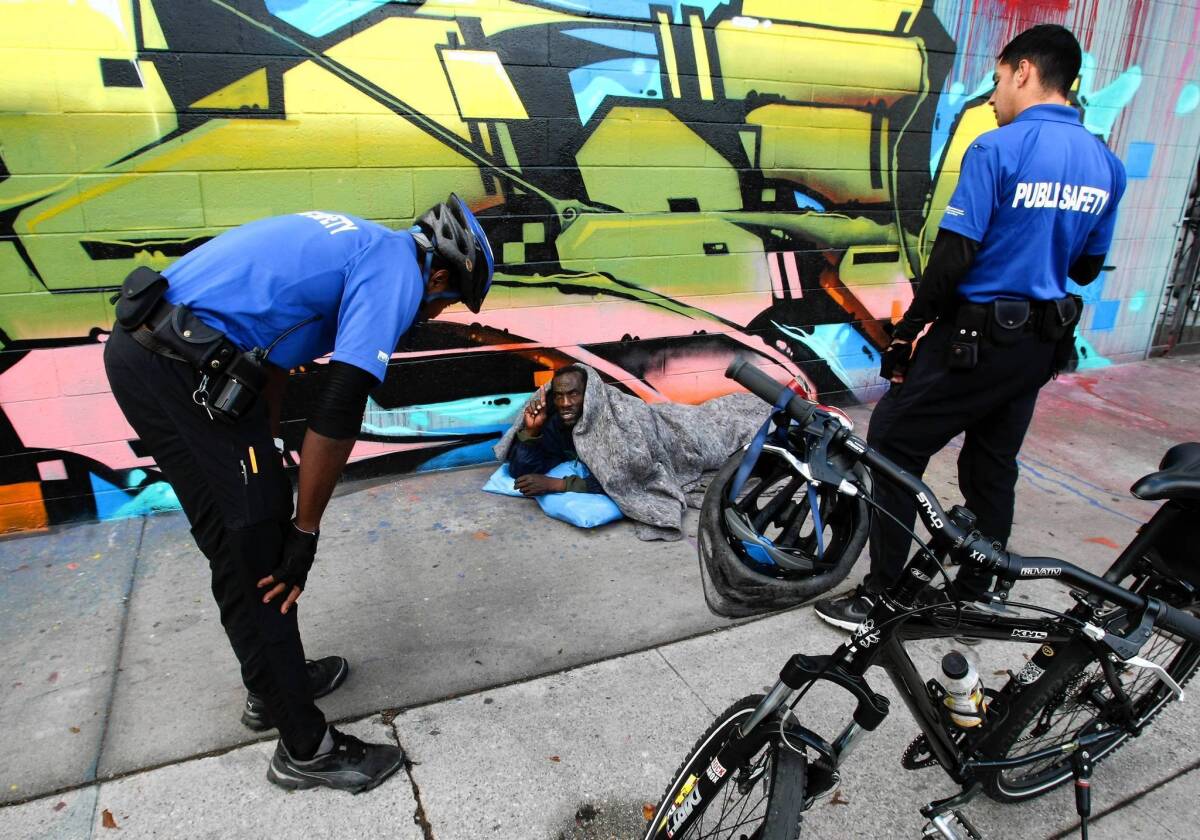

At the start of each morning, a private army of workers descends on downtown Los Angeles in bright-colored shirts, providing security, collecting trash, scrubbing graffiti, power-washing sidewalks and otherwise keeping downtown presentable.

The crews work for downtown’s network of business improvement districts and have become familiar parts of the area’s fabric. Many in downtown credit the business improvement districts, or BIDs, with helping turn around the once-desolate downtown, providing the kind of aggressive maintenance and security services that City Hall simply cannot afford and helping to market the area to new investors.

But this extra layer of municipal services doesn’t come cheap: together, the eight districts collect more than $15 million in annual tax assessments, which come on top of the regular taxes local businesses and residents pay for city services.

Now, some in downtown question whether the BIDs are worth their hefty costs. Two of the largest downtown improvement districts are facing lawsuits from property owners who no longer want to pay their fees, which in some cases top $100,000 a year.

Some critics say the BIDs have too much of a Big Brother feel, describing them as a kind of police force under the control of private executives whose aggressive cleaning up can sometimes feel like harassment. In the arts district, critics have posted bright orange “RID THE BID” banners and launched a petition online.

At the heart of the conflict is also a larger question: Should BIDs be a permanent part of downtown or something temporary — like training wheels for an area now gentrified enough that it can ride on its own.

“This concept of BIDs, for me, is kind of something of the ‘80s and ‘90s,” said Yuval Bar-Zemer, a loft developer in the arts district who brought one of the lawsuits. “I think there are better ways to enhance the quality of life.”

There are more than 80 business improvement districts across California, including Hollywood, Brentwood and Monterey. But they are coming under increased legal scrutiny; in addition to Bar-Zemer’s case, the owners of the Angelus Plaza have targeted the Downtown Center Business Improvement District in a lawsuit, saying they should be exempt from the agency’s fees. Similar disputes have been popping up throughout the state in recent years.

Cases against the BIDs generally argue that because they provide a general community benefit — such as security patrols or sidewalk sweeping — it’s unfair for property owners to be asked to fund them exclusively. Legal experts said they expect the state Supreme Court to weigh in on the issue soon.

::

For Estela Lopez, it’s hard to forget the way some streets in downtown L.A. looked in 1993, when she started the area’s first BID on Broadway.

It was a year after the L.A. riots, and many parts of the Central City were still recovering. Downtown was a “desolate ghost town,” she recalled.

The idea of the BID was to tax local businesses and use the money to keep streets clean, encourage economic development and serve as a lobbying force at City Hall and other government agencies.

As a change in state law allowed them to assess property owners, the BIDs in downtown began to spread and flex their political muscle. BID leaders became major advocates for Staples Center and the city’s adaptive reuse ordinance, which allowed for old office buildings in the Central City to be more easily converted into residential lofts and apartments.

BIDs now cover almost every foot of downtown, from the Figueroa corridor around USC to the skyscrapers of the financial district and shopping malls in Chinatown and Little Tokyo.

Lopez runs BIDs in the industrial core and arts district through an organization called the Central City East Assn. The work involves everything from networking with city officials and courting developers to overseeing security operations. She and her staff lead tours of the area for investors and home buyers, and consult regularly with Los Angeles police.

“Don’t let anyone kid you, the heavy lifting is done by the BIDs,” Lopez said in an interview. “We brought the developers here. We brought the investors here.”

On a recent Friday morning, George Peterman, Lopez’s operations director, found himself on Ceres Avenue, trying to persuade a homeless man to take down a 12-foot fort he’d built on the sidewalk.

Peterman, a burly, 67-year-old former LAPD sergeant, was friendly but firm.

“It’s an everyday deal,” he said. “We don’t take no for an answer.”

Kuo Yang, a small-business owner downtown, said the Downtown Center BID helped guide him through the complexities of opening a boutique last year on 7th Street. He found a location for his storefront during a tour through the area with one of the BID’s top executives.

In the first months after he opened for business, Yang said he was constantly dealing with thieves and “volatile homeless people” wandering over from skid row. Whenever there was a problem, he called the “purple shirt” guards from the improvement district.

“I’m here working a retail register with little ladies and purses and things,” Yang said. “The BID was very effective with their security detail. They respond much faster than the police because this is petty crime; the police are tied up with bigger challenges.”

Supporters of the BIDs are also quick to note problems in the small zones of downtown the districts do not cover: piles of detritus and drug use on San Julian Street, just outside the boundary of where Peterman’s groups patrol, or trash on the streets in the toy district, where property owners dissolved their BID in 2009.

Councilman Jose Huizar, who represents much of downtown, went as far as to say it would be “dangerous” for the city not to have BIDs.

But others in downtown disagree. Bar-Zemer said the BIDs have become an unnecessary bureaucracy. In the arts district, he said some individual homeowner associations in loft buildings feel they can handle security issues on their own and don’t want to pay the taxes to the BIDs.

Some legal experts believe the BID critics have a point. In Bar-Zemer’s suit against the Arts District BID, a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge recently ruled that the district’s public relations programs did not meet the standard of a “special benefit” required under state law. City attorneys representing the district said they would consider an appeal.

Bar-Zemer said he hopes the case will lead to new guidelines set by the city on the formation of business improvement districts, so they are created only in places where there is a very strong demand.

He says that Lopez and her board drew the boundaries of the Arts District BID around his loft buildings despite the objections of residents, and that they stacked the voting process by including large public parcels. (Votes are weighted based on parcel size in BID renewal elections, which are held once every five years.)

“The BID kind of took the liberties to assume as if they’re representing the neighborhood, which they’re not,” Bar-Zemer said. “It’s a small group of people who figured out how to manipulate the system.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.