Big-bucks battle shaping up over bid to raise malpractice award limit

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — You don’t need to be a Nobel economist to understand that dollars today aren’t anything close to their worth four decades ago.

Gasoline, real estate, medical care—they’ve all skyrocketed in cost.

Everything’s gone up, that is, except damage awards for pain and suffering caused by medical malpractice.

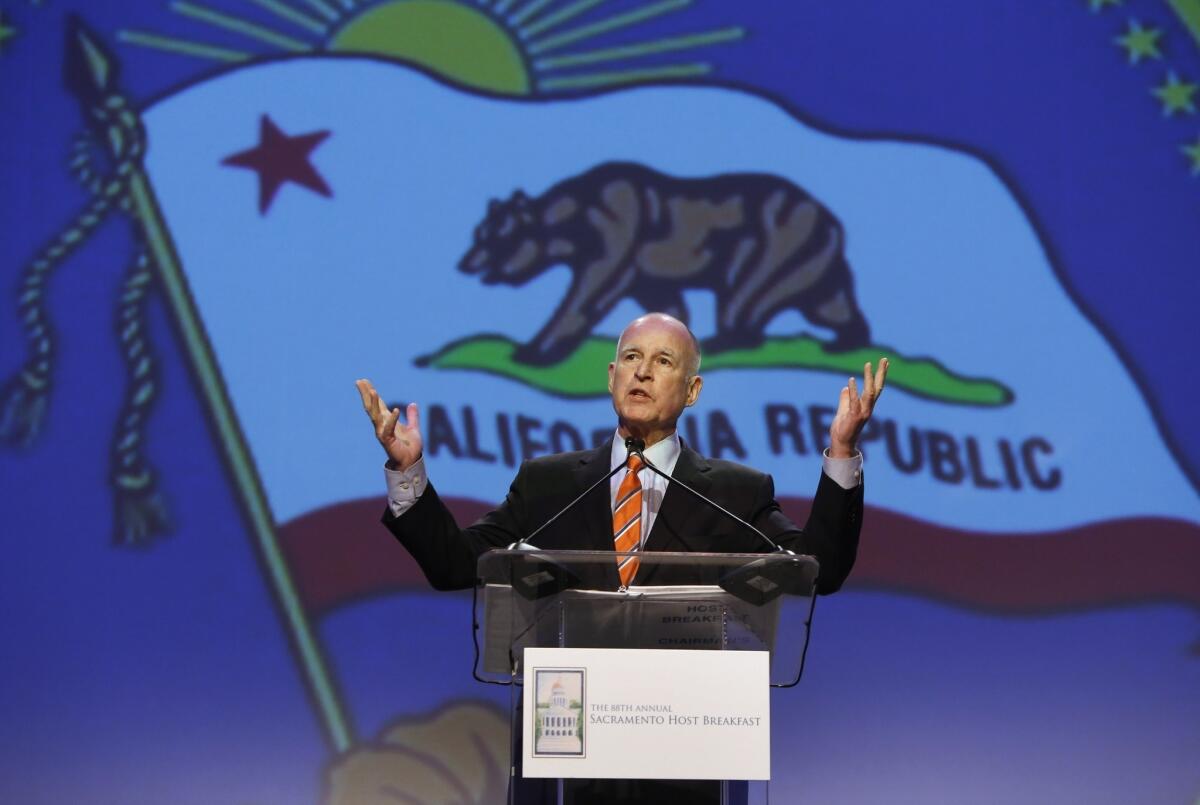

In 1975, the Legislature passed and Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill capping pain and suffering damages at $250,000. And that’s what it still is today.

If that $250,000 had been indexed to keep up with inflation, it would be worth $1.1 million.

Put another way, today’s $250,000 would have been worth $57,600 back in 1975.

There is no cap, however, on awards for economic losses—such as from potential income or for healthcare costs. If someone’s death from medical negligence puts the family in a bad financial strait, or the person requires expensive caregiving, the sky’s the limit.

But mere pain and suffering is worth only $250,000 tops, and frequently not even that.

So a ballot initiative proposed by consumer activists, trial lawyers and a wealthy, irate father whose two children died because of medical carelessness was submitted Wednesday to the state attorney general. After the AG writes a title and summary, the initiative will be circulated for signature-gathering to qualify it for the November 2014 ballot.

The measure would adjust the cap for inflation, raising it to $1.1 million. And it would require annual inflation adjustments.

“All we’re really talking about is putting the law back in place where it began,” says initiative strategist Chris Lehane, who once worked for Bill Clinton and Al Gore.

But the initiative also would do two other things: It would mandate drug and alcohol testing for physicians who work in hospitals. And it would require doctors to use a state database that tracks patients’ prescription drug histories.

“We require pilots and bus drivers to go through mandatory testing,” says technology entrepreneur Robert Pack, who’s bankrolling the initiative, at least initially. “Patients have a right to know that doctors they’ve entrusted with their lives are not abusing drugs or alcohol.”

Pack also is very concerned about over-prescribing addictive pain medicine. He has a personal reason to be.

Ten years ago, on a balmy Sunday evening in the San Francisco Bay Area, his two young children—Troy, 10, and Alana, 7—were walking with their pregnant mom to an ice cream store when a car jumped the curb and ran over them. The two kids were killed. Pack’s injured wife survived, but lost the twins she was carrying.

Turns out the driver was stoned on prescription drugs chased with vodka. She was caught trying to flee the country and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Pack tried to sue the giant medical group where the driver had “doctor shopped” to obtain hundreds of painkillers. But he had a hard time finding an attorney willing to take the case because of the $250,000 cap.

“Attorneys will tell you it’s going to cost more than $250,000 to navigate three years of court proceedings and hire experts,” Pack told me. “It’s a huge runaround. Victims are going to get shut out.”

He finally found an attorney who settled out of court for less than the maximum.

“I personally feel that the loss of my two children is worth a lot more than $250,000,” Pack says. “But the state says they’re worth, at most, $250,000.”

Not surprisingly, insurers and medical providers are united in opposition to raising the cap.

They argue it would stimulate frivolous lawsuits and drive up malpractice insurance premiums, thereby raising the cost of healthcare and making it even less accessible for poor people. Doctors will retire or leave the state, it’s claimed.

“Beverly Hills will never have a doctor shortage, but Bakersfield will,” says Kathy Kneer, president of Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California. She’s especially concerned about a potential shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists.

Louise McCarthy, president and CEO of the Community Clinic Assn. of Los Angeles County, says “liability insurance is a major cost driver. We want to make sure every patient has access to quality care. And clinics will not be able to provide care if they cannot afford to purchase malpractice insurance.”

Nonsense, says Jamie Court, president and board chairman of Consumer Watchdog, a cosponsor of the initiative. “Malpractice costs—claims and premiums—amount to about one-half of one percent of all healthcare costs. It would be mathematically impossible for malpractice costs to impact healthcare costs.”

So you get the drill: This is headed for a big-bucks battle at the ballot box, costing both sides tens of millions of dollars—unless the Legislature can settle the issue. And that’s not likely.

“The lawyers’ interests have made a strategic mistake,” Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez (D-Los Angeles) told NBC4-TV last weekend. Instead of trying to compromise on legislation, Perez asserted, “they’ve gotten [lawmakers] saying, ‘Fine, take it to the ballot….A pox on both sides.’”

Senate leader Darrell Steinberg (D-Sacramento) is hoping for compromise, but wants both sides to negotiate and deliver their solution to the Legislature. No heavy lifting for the politicians.

Meanwhile, the governor is avoiding the fight.

You’d think this would be simple. Just adjust the 38-year-old dollar amount for inflation.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.