A grounded view of the empire of insects

- Share via

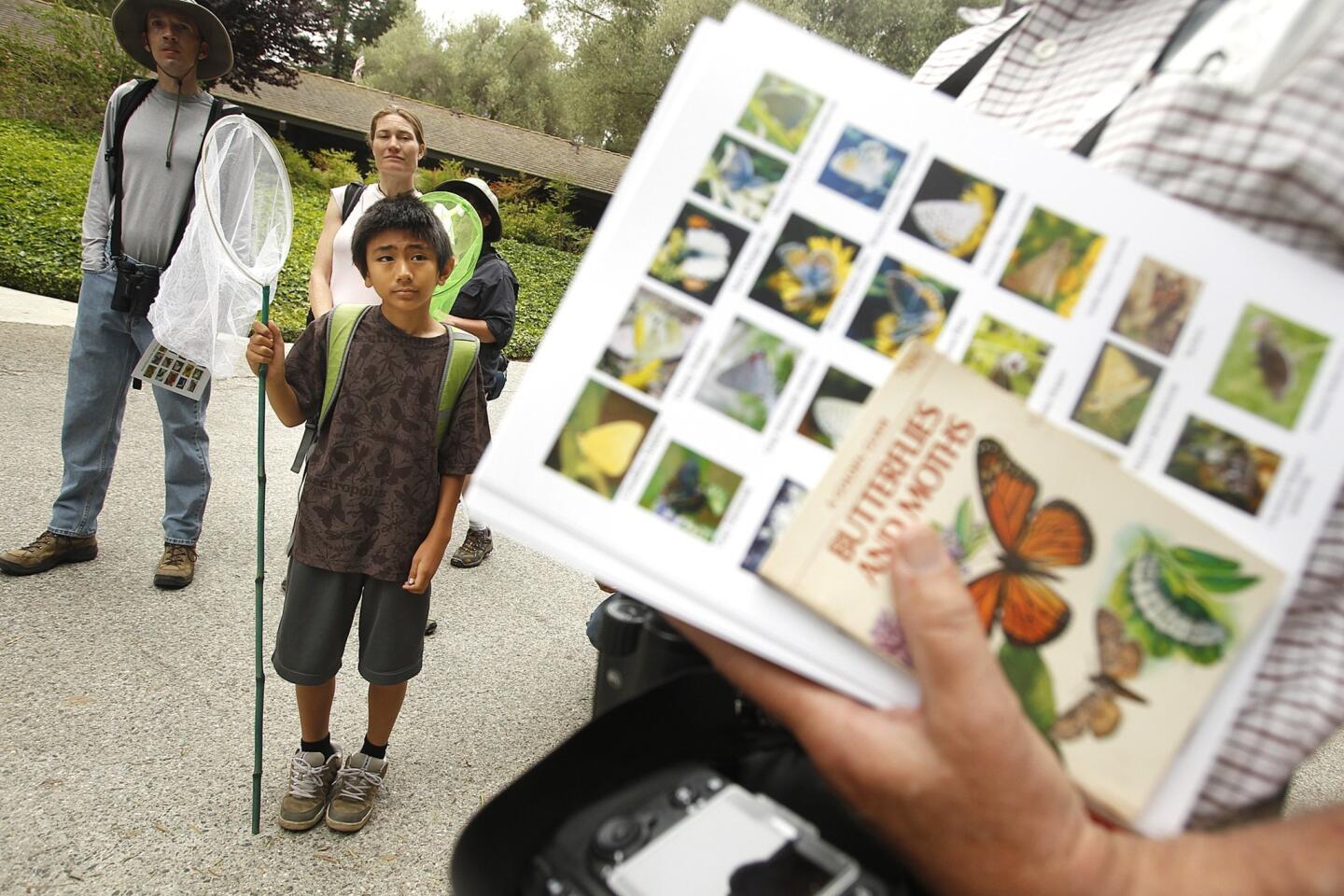

Max Ataka loves insects. All kinds, from the beetles on his T-shirt to the Anise swallowtail butterfly perched on the back of his hand. The 12-year-old loves the colors, the weird behaviors, the fact that he can actually handle them.

“When I was a baby, my first insect was a grasshopper,” he said, recalling the memory as if it were from a distant era.

Max is the youngest member of the Lorquin Entomological Society, an organization of Southern Californians who prefer six legs to four (or two). To them, “spineless” is a compliment.

For a century, the group has convened to share collecting tips, hear about new discoveries and chase bugs. On a recent Sunday, Max and several other members gathered in a parking lot in Rolling Hills Estates to count butterflies on the Palos Verdes peninsula.

Toting glass jars and white mesh nets with long wooden handles, this gang of biophiliacs stutters its way along the windy trail, stopping every couple of paces to watch and wait. Where others see a delicate tree branch blowing in the breeze, they see a small black bullet with yellow spots perched among the leaves — the golden spotted oak borer beetle.

It’s a throwback to a simpler time, before Kindles stood in for books and when FaceTime actually meant talking face-to-face. Such gatherings serve as a reminder that no matter how virtual society becomes, the allure of the outdoors endures.

But its pull is not as strong as it used to be, especially among kids: Max is one of only three Lorquin members who have not yet graduated from high school.

It all began in 1913, when Fordyce Grinnell Jr., a teenager with a particular zeal for butterflies, placed an ad in a Los Angeles newspaper announcing a meeting for boys interested in natural history. Grinnell called the gathering the Lorquin Natural History Club in honor of the 19th-century French entomologist Pierre Lorquin, who worked in California during the gold rush years and discovered a butterfly that became known as Lorquin’s admiral, among other species.

In 1927, the club changed its name to the Lorquin Entomological Society and convened its monthly meetings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

It was a golden age for entomology, riding high on the momentum of Victorian England’s fascination with natural history. Its favored status continued after World War II ended and the U.S. prioritized scientific research, particularly the development of insecticides to improve agricultural production. Government agencies like the National Science Foundation and U.S. Department of Agriculture showered money on universities to do that job and to conduct basic research on insect taxonomy, behavior and natural history.

Societies like Lorquin grew and expanded, welcoming both professional entomologists and amateurs who simply had a thing for bugs.

The roster has always included a fascinating cross-section of society, reaching far beyond the rarefied halls of academia. Ed Gilbert, who appeared in the 1970s TV series “Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries,” was a Lorquin member and avid collector of longhorn beetles. So was Charles F. Richter, the seismologist who invented the Richter scale.

Entomologists can be a lot like the organisms they study: fastidious, persnickety, territorial. To be passionate about creatures whose magnificent complexity is often visible only under a microscope — and to overlook the obvious “ick” factor — you have to be a little, well, different.

The Lorquin members are no exception. At one point during the butterfly hunt, they spend several minutes ogling a sarcophagid, a bristling monstrosity of a fly that gives birth to live maggots in feces or corpses.

David Faulkner leads the troop of butterfly-seekers through the oasis of willow trees and buckwheat in the Palos Verdes Peninsula Land Conservancy. A forensic entomologist who instructs police officers on how to reconstruct homicides by examining insects found on corpses, he fields questions patiently and turns every wildlife observation into a teachable moment.

The path winds into a garden of native plants in full bloom. Faulkner catches a glint from the emerging sun, and — whoosh — sweeps his net across the ground. Everyone crowds around, jockeying for a glimpse.

“Cabbage white,” someone calls, identifying the small, dainty white butterfly before it is let go.

When they’re not doing field work, these kindred spirits gather on the fourth Friday of every month at Bioquip, a company in Rancho Dominguez that sells traps, microscopes and other gear for entomologists. There are lectures on insect natural history, and members often conduct show-and-tell sessions featuring their recent catches. (Some are kept alive as pets; others are mounted for display.)

Faulkner, who has been the group’s president for two years, sometimes frets about the future. Since he joined Lorquin in 1975, entomology has lost some of its luster.

“Young kids used to go outside and collect insects,” he said. “Now, people don’t do that.”

A society founded by kids now can’t attract them. Why are members like Max such an anomaly?

Children today spend too much time plugged into electronic devices, doing homework and participating in organized activities, said Richard Louv, who described society’s collective “nature-deficit disorder” in his book “Last Child in the Woods.”

“They’re not getting the chance to develop a personal connection with nature that past generations did,” he said.

Even professional entomologists have had trouble staying relevant in a scientific world that increasingly favors molecular-scale research. In American universities across the country, old-school departments like entomology, botany and zoology are being replaced by interdisciplinary entities with names like “integrative biology” and “ecology and evolutionary biology.”

The Entomological Society of America has seen its membership drop from a high of 7,776 in 1986 to about 6,600 today.

“Once upon a time, entomologists were very much natural historians,” said Rob Wiedenmann, the society’s president and head of the entomology department at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. “It’s hard to be that anymore. You don’t get promoted based on natural history observations and studies. Academic institutions are looking for areas that are new.”

Faulkner, whose knowledge of insects has helped put murderers and rapists behind bars, has a hard time placing his finger on exactly why bugs have gone out of style.

“It looks old and crude, there’s no practical benefit,” he said, parroting his critics. “But it’s important. It tells us what’s going on in the real world.”

So far, the Lorquin Entomological Society is holding its own.

In 1965, at entomology’s zenith, there were 107 members. Today, there are 106.

Including Max.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.