Behind the debate: Read the changes to rules for L.A. charter schools

- Share via

Los Angeles charter school leaders won changes to the rules under which they operate last week after they put pressure on the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Students, they say, will benefit. But some district officials say that it is better for students that the charters did not get everything they wanted.

Here is a look at what the district agreed to change, where charters backed down, and what might happen next.

Services to disabled students

Changed

The rule: A charter school “reserves the right” to work with an agency other than L.A. Unified to provide or pay for services to disabled students.

How best to educate the disabled has long been a point of contention. Though all public schools have an obligation to provide a free and appropriate education to all students, neither the state nor the federal government provides anywhere near the funding necessary to cover the extra expenses of serving the disabled, especially those with moderate to severe disabilities.

Some charters have been accused of making it harder for disabled students to enroll or remain in their programs. Others have been faulted for serving mainly those with milder disabilities, whose education costs less.

L.A. Unified extracts a portion of the cost for the more expensive students by essentially taxing charters who take part in its regional special education program. The district is able to provide classes for students with rarer disabilities and oversee charter schools’ own efforts. But under state law, charters don’t have to use L.A. Unified’s program. They can use the services of any education agency in the state.

Several years ago, a large group signed up with the El Dorado County Office of Education, several hundred miles to the north.

El Dorado officials insisted that they provided sound supervision of the charter schools’ special education programs.

And they didn’t require L.A.-based charters to pay a share for students their schools weren’t serving. So the charters saved money while El Dorado got a windfall from the fees they paid.

L.A. Unified eventually managed to bring most of these charters back into the fold, in part by asking less of them financially but also by adding rules that made it more difficult for charters to contract with other agencies such as El Dorado. Charters worried that their authorizations would not be renewed if they didn’t contract with L.A. Unified.

Last week’s changes in the rules spelled out a charter’s right to contract with an agency other than L.A. Unified for special education.

Critics fear that charter operators now will have the freedom to search out the cheapest agencies, regardless of standards. In fact, under state law, they already had that option.

Charter leaders insist that the change was needed to stop the district from pressuring them to pay for special education programs that they think are inadequate or overpriced.

L.A. Unified could lose if many charter schools now look elsewhere to meet their special education requirements.

Powers of inspector general

No change

The rule: Charters are “subject to audit by LAUSD, including, without limitation, audit by the District Office of the Inspector General.” Charters “shall cooperate with any...inquiry and/or investigation undertaken by the District and/or the Office of the Inspector General Investigations Unit.”

Charter schools wanted very much to limit the inspector general’s authority to investigate. They complained that such investigations have been secretive, burdensome and so open-ended that they sometimes last several years.

The timing seemed right to push for change after control of the school board shifted in July to a majority elected with major financial support from charter backers.

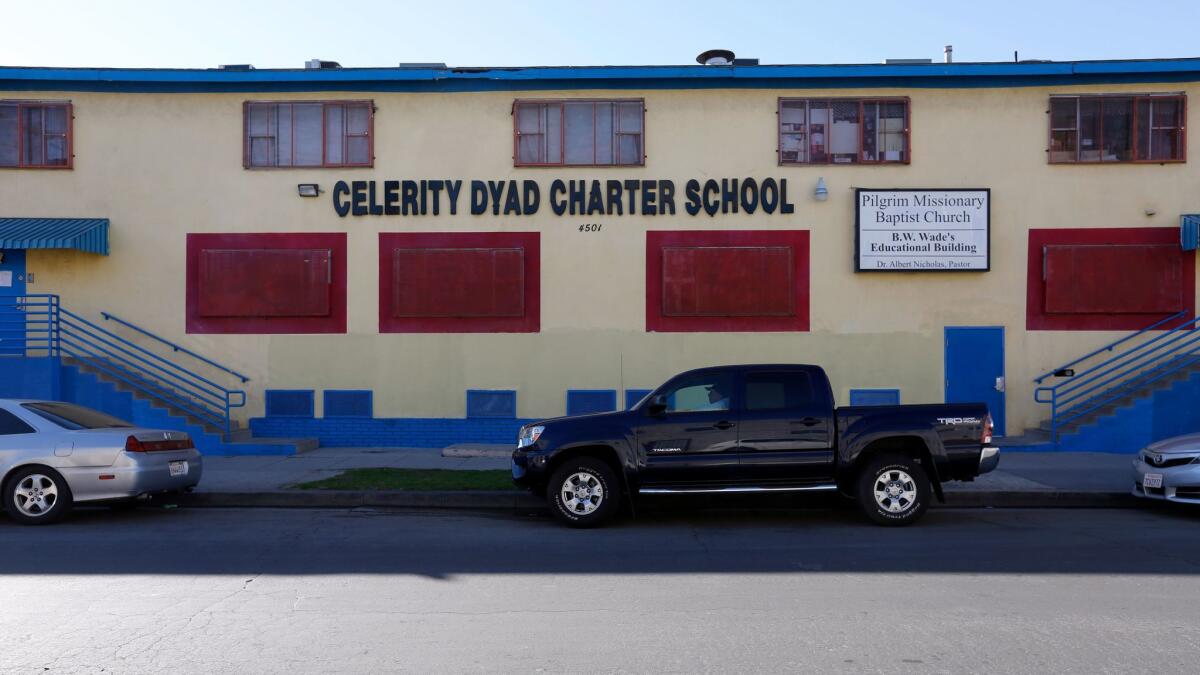

But in last week’s deal with the district, charter leaders did not insist on this point. Recent events worked against them: two long-running inspector general investigations that appeared to have legs. Celerity Educational Group was raided by the FBI. And PUC Schools, which was co-founded by board member Ref Rodriguez, contacted local and state regulators alleging that Rodriguez had conflicts of interest when he authorized a series of payments while he was employed there. Rodriguez faces unrelated criminal charges for alleged political money laundering, and has denied any wrongdoing.

For now, Inspector General Ken Bramlett retains his formal authority, but he has no civil service job protection. Board members who want to respond to complaints from the charters also could use the budget to cut back his activities.

Following district policies

Changed

The rule: Charter schools must comply with district policies as they relate to charter schools and are “adopted through Board action.” The district will compile a list of such policies by April 1, 2018 and annual changes must be approved by the Board of Education.

This new language could prove to be the most important. Before, at least in principle, charters were expected to follow all district policies. Now, they must follow only those policies that are required by law or that the school board, whose majority was elected with major support from charter advocates, votes to apply to them.

Before, the administrators of the district’s charter division could change rules for charters based on their own professional judgment and experience. The school board could overrule their decisions, but rarely did. Now, any proposed changes would have to be approved by a more charter-friendly school board.

With this opening, charters could also lean on board members to vote to change other rules. For example, some charters object to having to abide by the district’s approach to student discipline. Under last week’s compromise, they still are bound by these district policies. But they now have a way to circumvent these and other rules.

Limits on leased campus space

Removed

The rule: Agreements that allow charters to use available space on campuses “shall be limited to one school year” and separate multiyear agreements “shall not exceed five years.”

These limits have now been removed, which could allow charters to become permanent fixtures on district campuses they are using.

In the recent fight over rules, charters mostly opposed district efforts to impose rules on them that went beyond state law. But when it came to their use of district campuses, they wanted L.A. Unified to do more than state law requires.

Under state law, school districts must make classrooms and other campus facilities available for charters in a way that is "reasonably equivalent" to what is provided to traditional schools. But these offers of space only have to be good one year at a time.

Charters have complained that the district really doesn’t want to share space and they’ve had to fight, sometimes in court, to enforce their legal rights to space. Parents of students in traditional schools, on the other hand, often complain that having charters on their campuses forces cutbacks to programs for their children.

Of the 224 independent charter schools in L.A. Unified, 89 are occupying district-owned space, according to California Charter Schools Assn., and more would want to do so. Forty-nine of the charters currently on district properties are there under the one-year agreements laid out in state law, while the others have arranged more stable — sometimes virtually permanent — occupancy.

Under the revised rules, the district also commits to settling disputes over campus space more quickly. This could provide more stability to charters trying to plan for the next school year.

Insurance flexibility

Added

The rule: Charter schools can now meet increased insurance requirements by banding together or in an approved “self-insurance program.”

L.A. Unified has been hammered in recent years by legal claims from sexual misconduct and other problems. To avoid being blindsided by similar lawsuits stemming from problems at charter schools, over which the district has limited control, L.A. Unified required them to purchase more expensive insurance.

Charters protested that the costs were exorbitant.

The compromise is that charters now are allowed to get better rates by buying in groups. They also can “self-insure,” meaning they can commit to paying such claims themselves. L.A. Unified retains the authority to approve or nix these alternative arrangements.

Twitter: @howardblume

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.