Must Reads: California beaches are supposed to be public. So why is the Hollister Ranch coast an exception?

- Share via

When California ordered property owners to provide beach access for all, Hollister Ranch made the case that the pristine coastline west of Santa Barbara deserved an exception.

With 14,500 acres connected only by private roads, ranchers argued it was impossible for each of them, as required by law, to provide a public route to the beach every time they sought a permit to build. So lawmakers allowed owners to pay a fee instead — with the money going toward a ranch-wide route to be built by the state “as expeditiously as possible.”

But decades later, no one has held up that end of the bargain.

The fees? Still sitting in the bank — and amounting to a lot less than the state envisioned.

The path to the beach promised to the public? Still just a promise.

The standoff continues to this day, with some of California’s most-coveted beaches and surf breaks closed off to everyone but landowners, their guests, select groups and those strong enough to paddle in through treacherous waters. Coastal officials faced public backlash this year when they gave up a key fight by agreeing to ocean-only access.

With renewed public pressure to open Hollister Ranch once and for all, many have dusted off old records and reexamined the special provision of the Coastal Act on page 110, part (b) of section 30610.8.

While other property owners up and down the coast have over the decades been forced to play by the rules, how did 8.5 miles of coastline manage to remain so private — and with so little scrutiny — for more than 36 years?

Ranchers had the money to continue a legal fight in perpetuity. They had the defense that nature, under their private stewardship, has thrived. And as the legislative history faded from memory, the political will to bring about change petered out.

“You’ve had a handful of extremely wealthy, powerful people who have doggedly fought and delayed access at every turn. … They have lobbied in Sacramento, and they have bought the best lawyers that money can buy,” Coastal Commissioner Aaron Peskin said. “But because of the public outcry and all the attention, everything has now bubbled to the surface.”

The long standoff

Initiated by voters and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in his first term, the 1976 Coastal Act was a response to unregulated shoreline development. Almost immediately after its passage, beachfront owners and interest groups across the state began jostling to amend or repeal sections of the law.

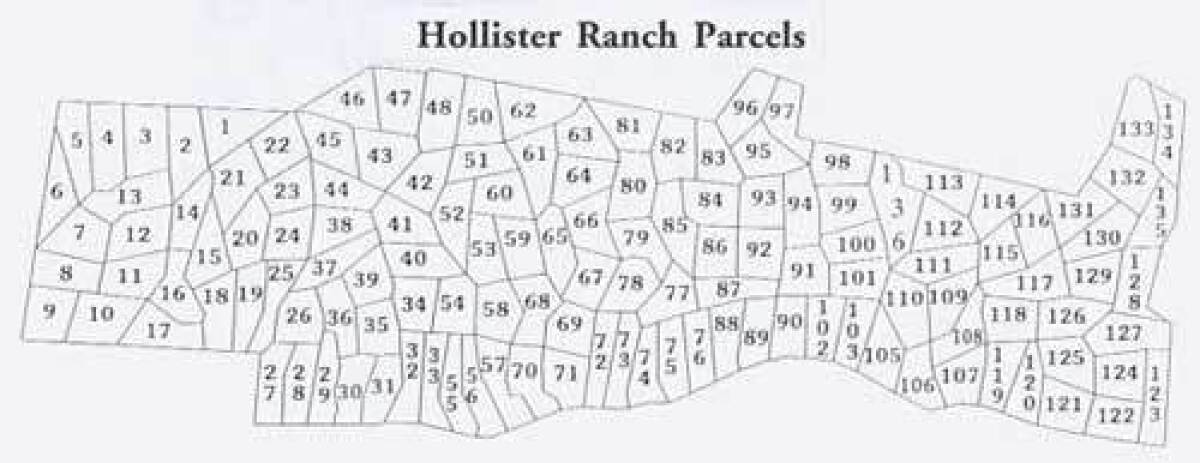

At Hollister Ranch, where a dozen owners could jointly own one of the subdivision’s 136 parcels, enforcing access rules proved particularly complicated. Property owners challenged this in court, saying that individual lot owners were unable to each provide a public accessway because the common roads were controlled by a third party — the Hollister Ranch Owners Assn.

The litigation pressed on, keeping landowners from developing their properties and the public from accessing the coast. The Legislature, in an attempt to resolve the standoff, added in 1979 a special section to the Coastal Act: Rather than require public access be provided parcel by parcel, permit by permit, owners could pay an “in-lieu” fee that would fund a public beach access program for the whole ranch.

Document

"Every person receiving a coastal development permit or a certificate of exemption for development on any vacant lot within an area designated pursuant to this section shall ... pay to the commission, for deposit in the Coastal Access Account, an 'in-lieu' public access fee."

— California Coastal Act

see the documentBut landowners resisted, according to public records, and blocked state surveyors from appraising the parcels needed to create the public path.

Coastal officials, using what site data they could gather, created in 1981 the Hollister Ranch Coastal Access Program. The plan included a walking trail and bicycle lane that would run parallel to the ranch’s main private road. To minimize the number of cars — in the interest of privacy and environmental protection — a bus would operate from nearby Gaviota State Park to six Hollister beaches, where there would be campsites and bathrooms.

Read the Hollister Ranch coastal access plan »

Still facing pushback, officials agreed in 1982 to implement the plan in three phases. The proposed campsites were removed. A cap was also set on the number of people allowed on the ranch each day, beginning with 100 people in phase one and a maximum of 500 in phase three.

But Hollister kept fighting, with the standoff now over the cost of the in-lieu fee. So the Legislature stepped in again and added another section to the Coastal Act, fixing the fee at “$5,000 for each permit” until the appraisal was completed and an official fee could be established.

Document

"... with respect to the Hollister Ranch public access program, the in-lieu fee shall be five thousands dollars ($5,000) for each permit."

— California Coastal Act

see the document“In the meantime, the Coastal Conservancy will be loaned $500,000 … so that work can begin immediately on the access program,” according to a legislative memo explaining each section of the 1982 bill. “The entire $500,000 will be repaid as individual fees are collected.”

Document

"Each of the 100 property owners will contribute $5000 to the access program when applying for a permit to develop his/her property... In the meantime, the Coastal Conservancy will be loaned $500,000... so that work can begin immediately on the access program. ... The entire $500,000 will be repaid as individual fees are collected."

— AB 321 (1982)

see the documentBut as Gov. Brown left office and Gov. George Deukmejian came in, the push to open Hollister lost steam. The attorney general in 1983 obtained a court order authorizing state officials to enter Hollister Ranch and complete the appraisal, but records show no evidence it took place. Other records show almost half of the $500,000 loan was spent on the fight to survey the land.

Deukmejian, who was in office from 1983 to 1991, sought to dismantle the Coastal Commission, which he viewed as a barrier to local control of development. The Legislature passed a few bills that would have given coastal officials more authority to carry out the Hollister access plan — he vetoed them all.

“That’s when the momentum really hit the wall in terms of access at Hollister,” Sarah Christie, the commission’s legislative director, said during a recent meeting. “The governor reduced our budget by 50%, we laid off half of our staff — so as you can imagine, the Coastal Commission itself got diverted in terms of its priorities on a day-to-day basis.”

Environmental purity

As other access battles took center stage and Hollister faded from institutional memory, the ranch remained a private oasis. Owners have long contended that letting the public in could spoil the ranch’s coastline and undo years of effort to protect the land. They point to the temporary access that they already grant to scientists, academics, historical societies, environmental groups and schoolchildren.

Over the years, this stance as private caretakers of the environment won the support from some members of the community. For a time, it even helped Hollister escape scrutiny by some of the state’s fiercest coastal advocates who until recently had focused their access battles elsewhere.

“I never really questioned it. I just accepted that they’ve always turned people away,” said Susan Jordan of the California Coastal Protection Network, who is now fighting for greater access with a coalition of advocacy groups through a court intervention. “Everyone here had just accepted that Hollister was an exclusive fiefdom of environmental purity.”

Read more: Coastal advocates challenge deal that bars public from reaching Hollister Ranch by land »

Carter Ohlmann, a research oceanographer at UC Santa Barbara, supports the environmental protection. He points to the high biodiversity that has thrived at Hollister without heavy human interruption.

Anthony Friedkin, a photographer who has visited the ranch since the 1960s, said that it makes him sad that the ranchers are “getting portrayed as these evil rich elitists.” Yes, some are wealthy, he said, “but to their credit they have been exceptional guardians of this exceptional land.”

He still recalls the first time he stepped onto Hollister — it felt spiritual, with packs of butterflies and wildlife that roamed free.

“I can’t even begin to tell you how overwhelmingly magnificent this land is, and it really deserves to be left alone and preserved,” he said. “There are so many beautiful beaches that the public can access in the area. Why not let this small stretch of land be without pavement, without parking lots, restrooms, trash and crowds so thick you can smell the sunscreen in the air?”

In a history book published by the Hollister Ranch Conservancy, its authors explained that the ranch “represents a concept of land development that is a model for both landowners and environmentalists — allowing very limited development and achieving conservation of habitat and resources, and sharing those resources for education and science … while still preserving property rights.”

“Given time, money and human sensitivity,” the book said, “the integrity of a magnificent piece of land such as the Hollister Ranch can remain intact.”

The fees

The special sections carved into the Coastal Act have given Hollister Ranch unique standing — but even that legal language is now in dispute.

The sticking point was the recent realization that based on the way the law was written, the sections addressing Hollister Ranch can be read a few different ways. And for 30 some years, no one had seemed to challenge the property owners’ interpretation of how the fees should be paid.

But based on the way state officials now say the law should be interpreted, the numbers don’t add up.

Santa Barbara County has issued 206 coastal development permits to Hollister Ranch since 1982, according to a Times records request. If the 1982 amendment to the Coastal Act did indeed require a $5,000 in-lieu fee per permit, that would amount to more than $1 million.

To date, officials have received only $295,000.

When asked about the discrepancy, Dianne Black, the county’s planning and development director, whose department is responsible for issuing the permits, said that the county had been collecting an in-lieu fee only as a one-time payment for the first coastal development permit issued on a vacant property at Hollister Ranch — not for every permit.

The Hollister Ranch Owners Assn., which represents the more than 1,000 people today who own a share of the ranch, also says the fee is a one-time payment per parcel, citing a clause that says the in-lieu fee is required for a permit seeking to develop “on any vacant lot” on the ranch. So if an owner built a house on an empty parcel and paid $5,000, their lawyers said, that’s the last fee they would have to pay.

If the fee was required for each and every permit, the lawyers said in a letter to state legislators, then “if the owner wants to build a barn, he pays another $5,000. If he wants to put up a fence … that’s another $5,000. An owner who puts up six different structures (barn, guest house, ag worker housing, etc) would pay $5,000 x 6 = $30,000.”

“There would be no limit to the number of times that an individual property owner would be subject to the fee. This is clearly not what the Legislature intended when enacting these provisions of the Coastal Act,” an attorney for the owners group wrote in a recent letter to the Coastal Commission, calling on officials to continue the practice of requiring a fee per vacant lot. “To do otherwise would be acting beyond its Legislative mandate and likely an unconstitutional taking.”

The 1982 access plan, they added, is obsolete and infeasible.

The Coastal Commission, now aware of this discrepancy, said it has updated the wording in local planning documents to clarify that the $5,000 fee is required for every project.

“Going forward, it’s going to be per permit, not per vacant lot. We made sure the county is clear on that,” executive director Jack Ainsworth said. “We’ll be monitoring all the permits coming in.”

The push to open Hollister Ranch had gone quiet until this year, when coastal officials ceded a claim to a public path in a controversial deal that many considered favorable to landowners.

Facing public outrage, the state started looking for ways to finish what it started decades ago.

A number of coastal commissioners, not enamored with the deal they approved, have begun speaking out. Two commissioners recently appealed a Hollister Ranch permit that had been issued to build a new house, guest house and footbridge — citing for the first time in decades that a condition of any permit, under the Coastal Act, is providing public access in a timely manner.

The panel will vote this month whether to overrule this permit, marking perhaps another legal avenue for public access.

At the same time, Gov. Brown rejected a separate attempt by lawmakers to open the ranch.

The legislation would have recommitted the state to the 1982 access plan and clarified the purpose of the in-lieu fees. It also laid the foundation for more aggressive strategies, such as acquiring private land for public use through eminent domain.

Brown said the legislation was well-intentioned — but years too late.

“Although this program could have been completed over three decades ago,” Brown wrote in his veto message this week, “it was not and it is now outdated.”

So he urged state officials to go back to the drawing board and craft a better plan.

Interested in coastal issues? Follow @RosannaXia on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.