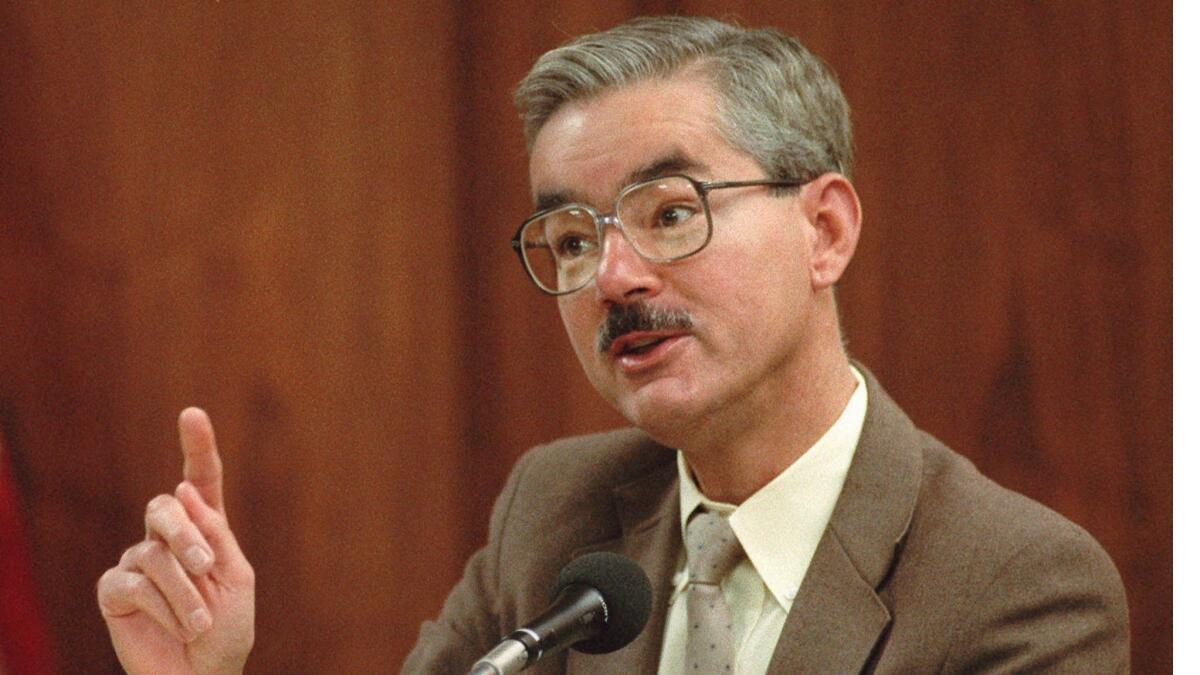

Psychiatrist who admitted altering notes in Menendez brothers’ murder trial in the ’90s surrenders license

- Share via

A psychiatrist who caused an uproar in the 1990s when he admitted altering clinical notes in the infamous Menendez brothers’ murder trial has agreed to surrender his medical license over new allegations of wrongdoing, according to the Medical Board of California.

The decision, which became effective last month, came after the state accused Dr. William Vicary of gross negligence, repeated negligent acts, prescribing without an appropriate exam, excessive prescribing and inadequate record keeping.

The complaint, filed in November 2017, details encounters from 1988 to 2016 between Vicary and eight patients — five of whom were undercover officers — and alleges he prescribed medications with a high potential for abuse without making an effort to obtain information necessary to establish whether a patient suffered from an illness or disorder.

“Virtually all the allegations are without merit,” Vicary told The Times on Tuesday.

In 2004, he began treating a 50-year-old patient who overdosed in 2014 from cocaine, hydrocodone and perhaps other substances. Over the years, Vicary had received many letters from the patient’s medical insurance companies stating that he was receiving a large number of prescriptions from multiple providers, the complaint said. Vicary continued prescribing him controlled substances, and in an interview with the medical board acknowledged doing so without conducting an examination or obtaining a history, according to the complaint.

Vicary told The Times that the patient was a neighbor and that he had been trying to get him to cut down on some of his medications. The patient, he said, always seemed to be “in good spirits and in regularly good health.”

“The cocaine killed him — it wasn’t anything that I gave him,” Vicary said.

In April 2015, Vicary prescribed Adderall to an undercover officer posing as a patient who said he would be taking it to help him study, according to the complaint. The next month, Vicary increased his prescription and later prescribed him Naproxen and Adderall. According to the complaint, Vicary at no point took “any meaningful medical or psychiatric history” from the patient and did not inquire into his substance use history after the patient acknowledged he had illegally obtained “a drug of abuse for non-medical reasons.”

In another case, Vicary prescribed another undercover officer Xanax and Ambien in June 2015 after she told him she was taking Xanax twice a day and Ambien every night and that the medications were intended “to balance her out.” He did not ask her directly about her history of mental health problems, about substance misuse or about any current symptoms, and diagnosed her with “stress/anxiety and insomnia,” the complaint stated.

Vicary graduated from Harvard Law School and USC’s medical school, and received his physician’s and surgeon’s license in 1975. According to the medical board’s records, he has taught forensic psychiatry on a volunteer basis at USC’s Keck School of Medicine and has served as president of the Southern California Chapter of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Vicary said he gives one or two lectures a year at USC, the last one six months ago, and that he is currently the treasurer of the AAPL’s Southern California chapter.

William G. Moore, the attorney who represented Vicary in the case, did not return messages.

The medical board accused Vicary of excessively prescribing drugs to multiple patients. In surrendering his license, Vicary did not contest that the state could establish a case that he excessively prescribed drugs to two of the patients, including the one who overdosed, according to medical board records.

The surrender of his license follows previous disciplinary actions taken by the board against Vicary. In 2012, his license was placed on probation for 35 months in relation to treatment he gave a patient who also worked for him as a psychological assistant. He repeatedly prescribed the patient dangerous drugs without obtaining patient history and without conducting an initial physical examination or subsequent periodic examinations, and he failed to monitor the patient’s progress, according to medical board records.

He was also placed on probation for three years in April 1998 in relation to his work during the high-profile murder trial of Erik and Lyle Menendez, who were convicted of fatally shooting their parents in 1989 at the family’s Beverly Hills mansion. Lyle was 21 and Erik was 18 at the time of the killings.

The brothers had alleged that they had been sexually abused by their father, while prosecutors said they had wanted their parents’ multimillion-dollar estate. After being appointed by Erik Menendez’s attorney to serve as a treating and forensic psychiatrist, Vicary “rewrote pages of his clinical notes deleting potentially damaging material, knowing that his rewritten notes would be provided to prosecutors and used in court as though they were originals,” according to medical board records.

Vicary had testified during the brothers’ second trial that he deleted two dozen statements Menendez had made about being molested by his father and hating his parents, and that he rewrote 10 pages of his notes at the direction of Leslie Abramson, Erik Menendez’s chief defense attorney, who he said threatened to take him off the case if he didn’t.

Abramson insisted in an interview with The Times that she never told Vicary to “erase,” “evaporate” or “rewrite” any notes of his sessions with Menendez. Rather, she said, she told Vicary to redact only information that a Superior Court judge had already ruled inadmissible in the brothers’ first trial.

The State Bar of California cleared Abramson of misconduct, but Vicary was removed in 1996 from a panel of mental health professionals who are appointed by county judges to analyze and testify about defendants in court.

“The downside is that it’s a negative and certainly not going to help my reputation,” Vicary said then. “The upside is that this work doesn’t pay very much and you kind of run yourself ragged driving to all these juvenile halls and local jails and hospitals.”

In his latest disciplinary case, Vicary reached an agreement with the medical board to surrender his license rather than present the case before an administrative law judge, said Carlos Villatoro, a board spokesman. If he files for reinstatement of his surrendered license, the charges in the 2017 complaint would be deemed true.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.