Q&A: Demystifying L.A.’s system of homeless shelters

- Share via

A shelter bed is the most fundamental homeless service, but in some ways the least understood.

Shelters operate almost entirely out of public view, face little scrutiny, support themselves in myriad ways and adhere to different philosophies.

There are those who think of shelters as the foundation of all homeless services and others who view them as part of the homeless problem.

Below are answers to common questions about shelters in the Los Angeles area.

How many shelter beds are there?

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority puts the number at 16,600 in 2017. If you add Long Beach, Pasadena and Glendale, which report their data separately, the total is about 17,800 — a little more than one for every three of the county’s 58,000 estimated homeless people.

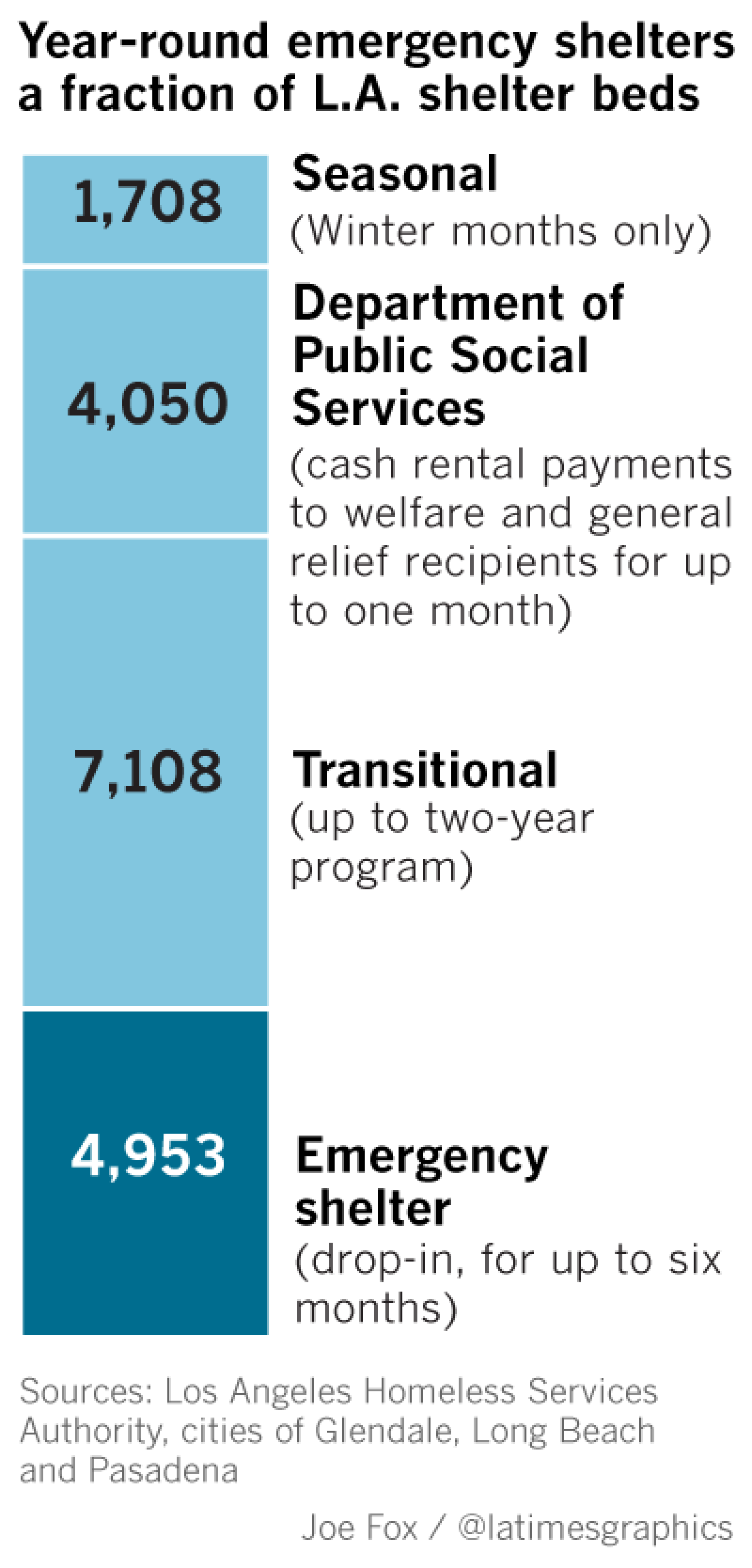

But not all of those beds are available year-round to people who would otherwise be living on the street. The combined count includes 1,700 shelter beds that are open only during winter and 4,000 that are not actually beds, but cash payments reserved for welfare and general relief recipients to rent rooms for up to a month. An additional 7,100 are in transitional programs that generally serve families and youth for up to two years and are not often open for drop-ins..

That leaves just under 5,000 traditional shelter beds available for people on a moment’s notice, year-round.

Fewer than 30% of L.A. homeless shelter beds are open year-round for drop-ins.

In a word, no — although distinctions among types of shelter beds and how they are counted complicate the picture.

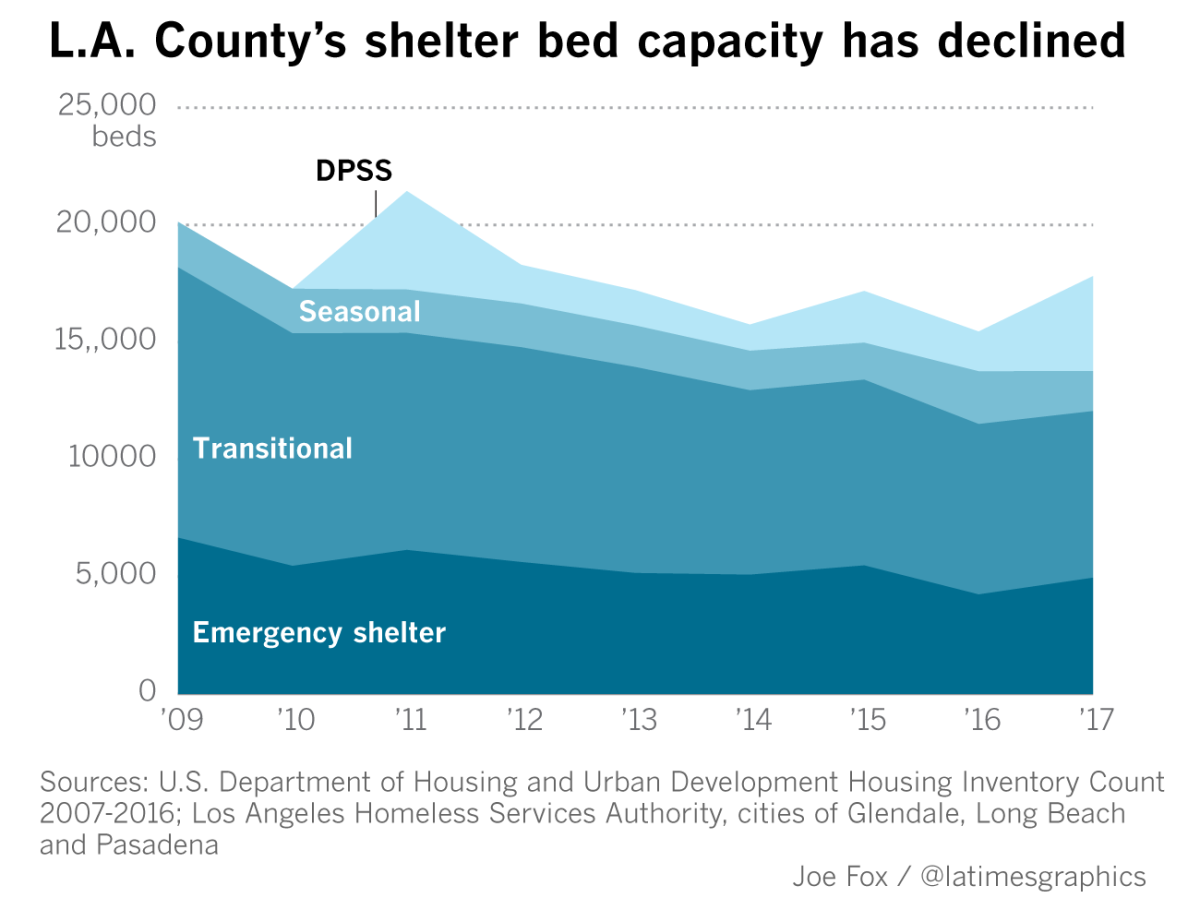

In 2009, the four homeless authorities covering Los Angeles County reported 18,192 year-round shelter beds. That figure included multiple types of shelter, but not beds controlled by the county Department of Public Social Services, or DPSS, that offer short-term refuge for welfare recipients. At that time, the county had 48,000 homeless people.

Today the homeless population has grown by 20%, while the shelter bed count has shrunk by 11%. Even that number is conservative. Excluding the DPSS beds — which are cash payments for motel rentals, not physical beds, and are good for only up to a month — the bed count is down 33%.

The homeless count climbed to more than 51,000 in 2011, then fell two years later to below 39,500. Since then, it has shot back up nearly 50%, reaching nearly 58,000 this year.

The bed count also peaked in 2011, but only because the DPSS beds were added to the county shelter rolls, boosting the total by more than 4,000 that year. Over the next three years, the bed count declined even with the DPSS figure included.

The four homeless authorities’ 2017 Housing Inventory Counts showed an uptick from only 4,240 non-welfare year-round shelter beds to 4,953, but a decline from 7,261 transitional beds to 7,108.

Timeline of L.A.’s declining homeless shelter capacity

How many more shelter beds are needed?

Answers to this question depend on the assumptions used in the estimate and the philosophies behind them.

Some argue that shelters represent society’s minimum obligation to provide a safe and sanitary quarters for anyone who loses their housing. They tend to see a joint responsibility of government and the nonprofit sector to be able to rapidly expand shelter capacity, as the

Others say homelessness can be managed with an arsenal of strategies to lead those who have become homeless back into housing as quickly as possible with support to prevent relapses. Once enough supported housing is provided, shelters would be needed only as a stopgap for about 15,000 people expected to become homeless each year.

A 2016 analysis by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority concluded that only 2,279 additional shelter beds are needed to fill the current gap.

Estimated additions and reductions needed to shelter capacity

The agency calculated that there are 2,861 too few beds for individuals and 402 too many shelter units for families. The same analysis concluded that there are currently 1,483 too many beds of transitional housing for singles and 377 too many for families. Family units have an average of 3.4 beds each.

These numbers are likely to be significantly revised in a new analysis expected this month.

How does the county homeless agency’s housing math work?

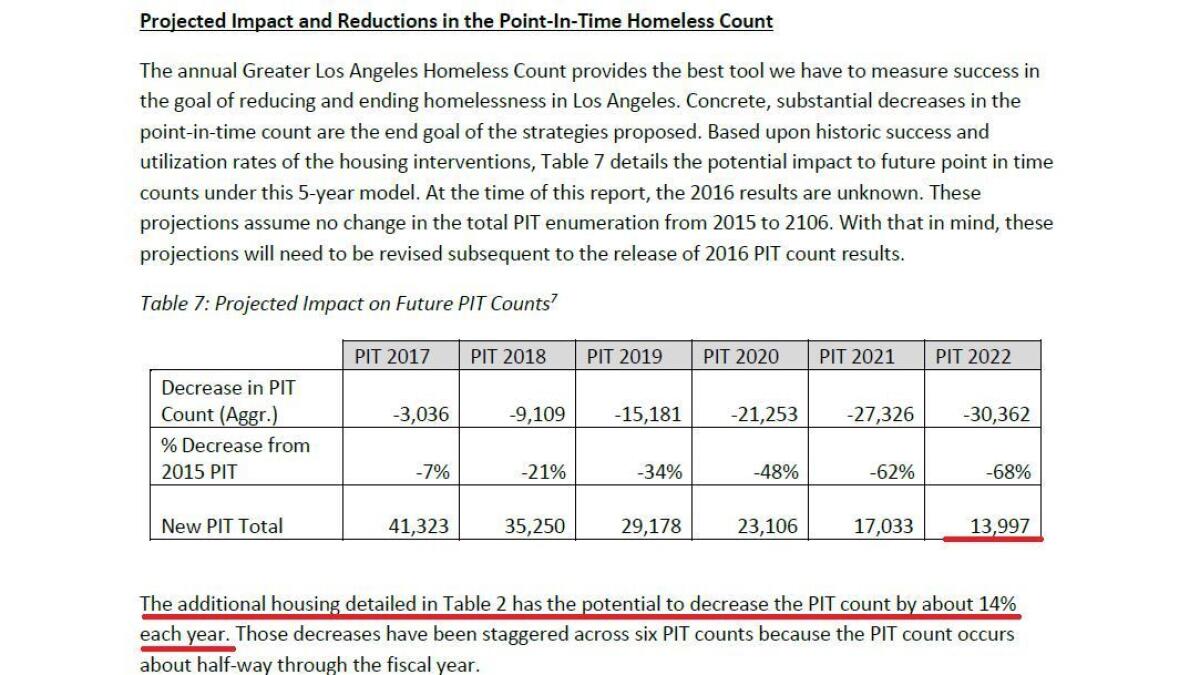

The Homeless Services Authority calculates that the homeless count can be reduced 14% each year with strategies to be funded by the multibillion-dollar measures approved by city and county voters. The agency envisioned, based on 2016 figures, that the number of homeless people at any one time would drop just below 15,000 by 2022 and would remain around that level from then on.

That schedule was set back by the 2017 homeless count, which saw a 23% increase over the previous year. The Homeless Services Authority is working on a new analysis reflecting that change. Funds from the two initiatives have only begun to flow, and an accurate measure of their effectiveness may not be possible until 2018 at the earliest.

The model rests on the assumption that people becoming homeless would require about six months in emergency shelter or rapid rehousing before securing permanent housing. Nine months may be a more realistic turnaround time, however, according to agency officials.

Projected timetable for reducing homelessness

Why did shelter capacity shrink while homelessness increased?

Several factors have combined to reduce the number of beds. Legislation passed by Congress in 2009 redirected emergency-shelter funds toward permanent housing strategies.

Responding to those changes, the Homeless Services Authority has eliminated the funding for hundreds of transitional beds, requiring many of them to be converted to permanent housing. It has also required bidders for shelter beds to provide more services, such as case management and housing navigation, with the goal of keeping shelter episodes brief and having them end in permanent housing.

The added costs have caused some operators to close shelters and dissuaded others from applying for shelter grants. The authority’s most recent request for proposals last year received no takers, said executive director Peter Lynn.

Last year the city of Los Angeles spent about $24 million on shelters. In the fiscal year that began in July, the city cut $10 million, anticipating that it will be made up by county funds from Measure H.

How much does a shelter bed cost?

A principal reason given for not providing a shelter bed for every homeless person is the expense: a shelter bed costs almost as much as it does to support a chronically homeless person in permanent housing.

The current reimbursement for what the Homeless Services Authority calls crisis housing is $40 per night — about $14,600 per year for each bed. By comparison, rental subsidies provided by the Los Angeles Department of Health Services, coupled with support services, cost about $1,450 per month, or $17,400 per year.

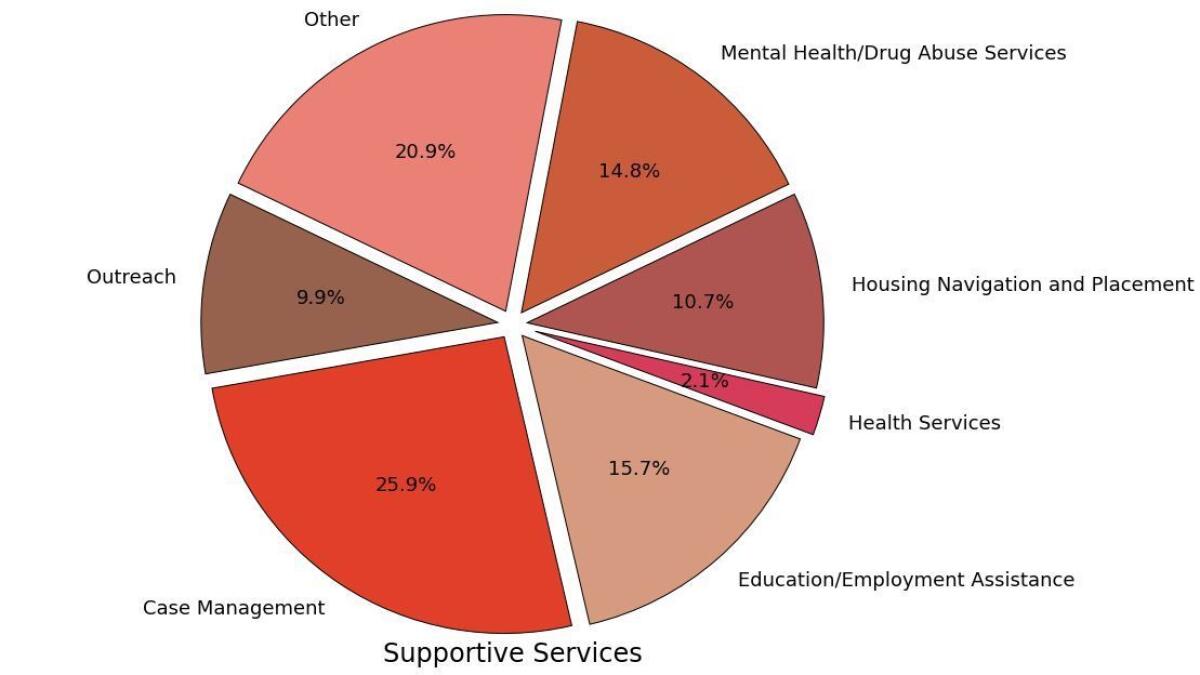

Shelters cost so much because they are required to do far more than provide overnight refuge. Their role has been redefined to make them responsible for the success of their clients in getting into permanent housing — at a cost.

The $40 reimbursement rate — to be raised to $50 this year for some shelters — has doubled in recent years as the homeless agency pushed shelters to do more.

A Times analysis of 35 shelter budgets obtained from the Homeless Services Authority through a public records request found that the actual cost of running shelters averages about $62 per bed per day.

Less than half of that is for keeping the shelter open — primarily operations, food, utilities and space. More than half went to supportive services, including case management, housing navigation and life skills training.

Breakdown of shelter supportive services

Most shelter operators piece together money from multiple sources and supplement it with private fundraising.

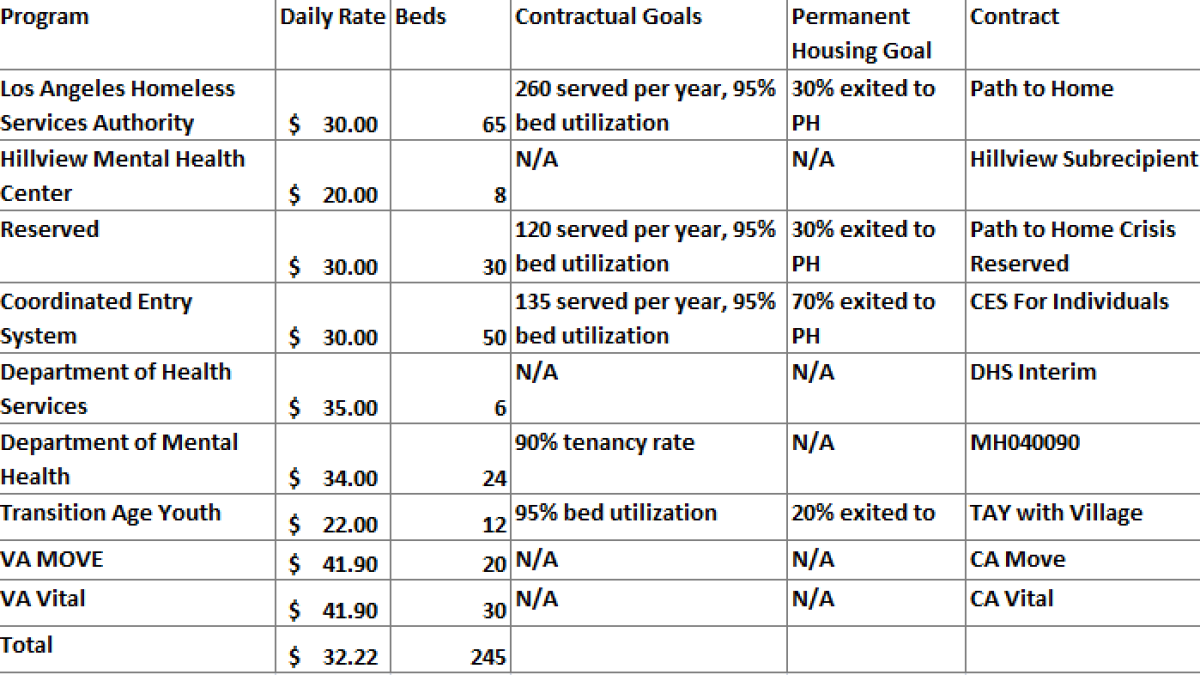

The San Fernando Valley agency operates a 245-bed shelter in North Hollywood. But the beds are contracted to nine different programs with differing performance goals and daily reimbursement rates ranging from $22 per bed to $41.90.

Shelter programs for single adults operated by LA Family Housing

What do all those names for shelters mean?

There are several kinds of shelter programs for homeless people. Their names are often used interchangeably, but there are differences. Some are reported to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as shelters, others are not.

Here is a glossary:

Transitional: A shelter program lasting up to two years and often in a homelike setting with services to develop skills for independent living. A decade ago, two of every three shelter beds were transitional. Since then, the transitional model has fallen out of favor as policymakers have shifted their priority to “housing first.” With dwindling funding, the number of transitional programs has been halved, and they are now considered most appropriate for victims of domestic abuse and youths, especially those leaving the foster care system. Transitional contracts require 65% of clients to obtain permanent housing.

Crisis: Generally the most basic setting, in which a person or family seeks refuge from the street for an indeterminate period with some degree of services to help them get re-established. For many the next step will be a longer-term program. Crisis contracts require 30% of clients to obtain permanent housing.

Interim: Temporary housing for those who have been accepted into a program that will provide subsidized permanent housing with services, allowing them to stay off the streets while securing a lease.

Bridge: Crisis housing backed up by intensive housing services and intended for those who have a good prospect of obtaining and keeping permanent housing. A bridge placement often follows a crisis housing episode. Bridge contracts require 80% of clients to obtain permanent housing.

DPSS: The Los Angeles Department of Public Social Services funds two hybrid shelter programs. One provides welfare recipients who become homeless vouchers for 16-day stays in motels. The other provides applicants for general relief with beds for up to 28 days or until their applications are approved. Then they can move into a regular shelter program from which they seek housing.

Recuperative: A special kind of shelter with medical support for those leaving hospitals.

But for the 35 agencies whose budgets were available, the authority’s reimbursement paid for more than half the operations, but only a quarter of the supportive services required by its contracts. The terms of the contracts require the agencies to “leverage” their grant with other services.

ALSO

L.A. Unified students toss out $100,000 in food a day. A new state law could donate it to food banks

ICE arrests hundreds of immigrants in 'sanctuary cities' around the nation, California

Complaint alleges harm to pregnant women in immigration detention centers

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.