Police blame reform for putting a convicted felon suspected of killing a Whittier officer back on the street. The record is more complicated

Michael Christopher Mejia was jailed and released repeatedly for violating his probation.

- Share via

Soon after returning to Los Angeles from Pelican Bay State Prison in April 2016, Michael Christopher Mejia was in trouble again.

An imposing physical presence at 6 feet, 3 inches, with face and neck tattoos that trumpeted his gang membership, Mejia was jailed and released repeatedly for violating his probation.

For the record:

4:33 a.m. July 13, 2025A previous version of this article misidentified Roy Torres, a cousin whom Mejia is suspected of gunning down, as Ray Torres.

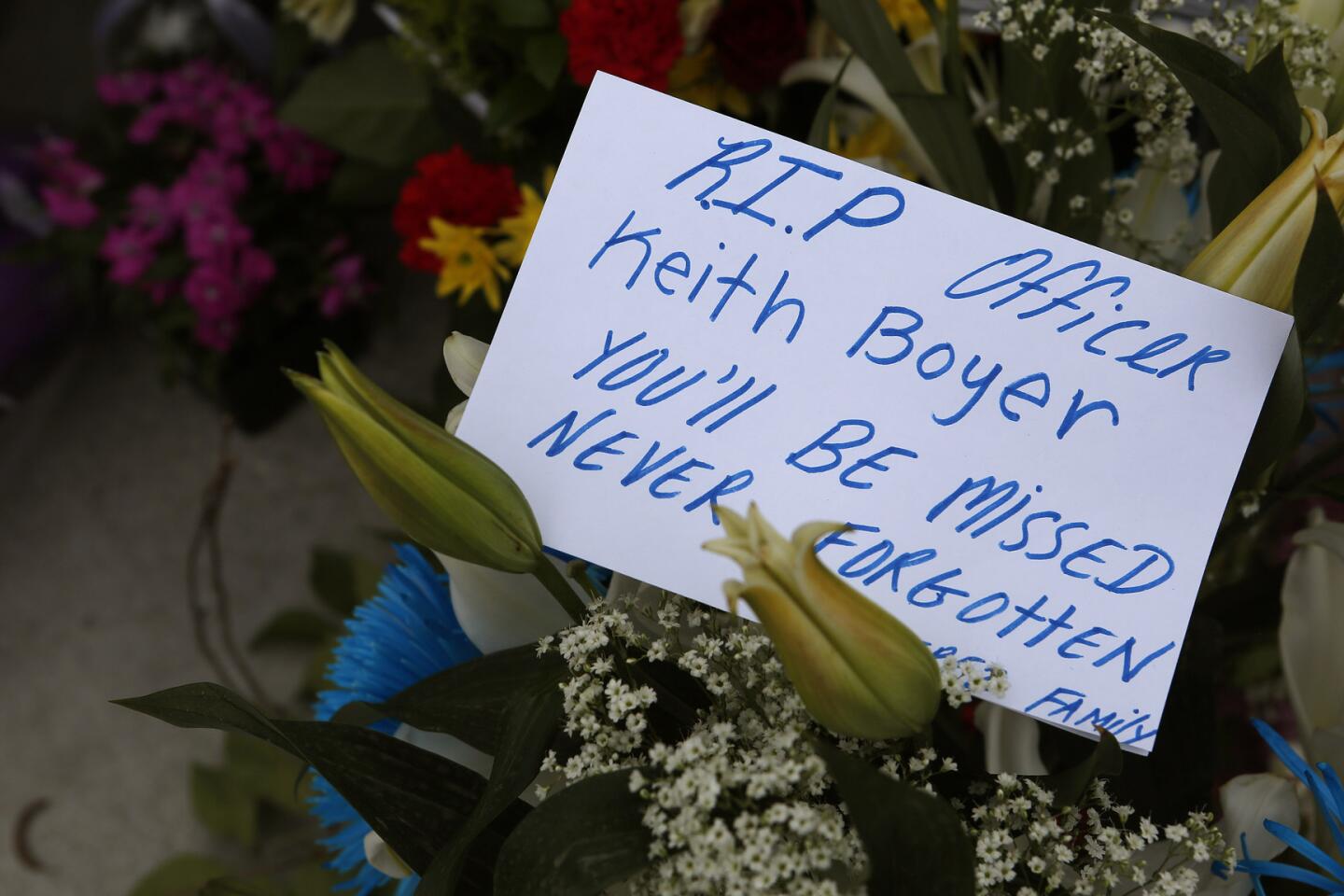

On Monday, just over a week after finishing his latest jail stint, Mejia fatally shot a 27-year veteran Whittier police officer and wounded another officer, according to authorities. Before engaging in the shootout with the officers, he is suspected of killing his cousin and stealing the cousin’s car.

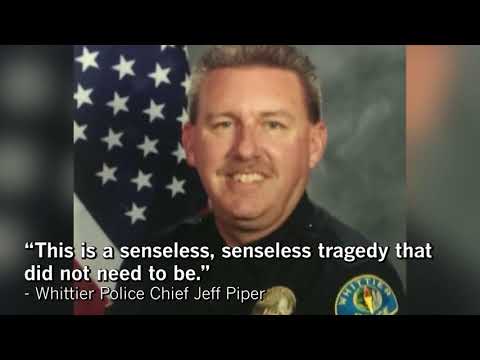

Hours after the officer’s death, Whittier Police Chief Jeff Piper took the podium at an emotional news conference and blamed recent criminal justice reforms for setting Mejia free.

State corrections officials have since stated that the time Mejia served — nearly two years for grand theft auto and attempting to steal a vehicle — was not shortened by laws designed to reduce the prison population. Mejia, 26, who was wounded in the shootout, had earlier spent over three years in state prison for a robbery.

But the reaction to the death of Officer Keith Boyer highlights the continuing controversy over Assembly Bill 109 and Proposition 47, two of the criminal reform measures that some local law enforcement officials have blamed for recent increases in crime.

On Tuesday, the union that represents Los Angeles Police Department officers asked U.S. Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions and California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra to review the effect the two measures have had on public safety.

“The senseless murder of Whittier Police Officer Keith Boyer is the latest tragic example of a convicted felon who recycled multiple times through our criminal justice system and, when not incarcerated, wreaks havoc on society,” Craig Lally, president of the Los Angeles Police Protective League, wrote in letters to Sessions and Becerra.

Two Los Angeles County supervisors, Kathryn Barger and Janice Hahn, on Tuesday called for an investigation into the accused killer’s release from prison last year and his supervision by the L.A. County Probation Department.

Hahn said she didn’t know whether the reform measures played a role in events.

“We need the facts and we need to look if there was any failure of protocol (by the county) that led to this terrible tragedy,” Hahn said in a statement.

Mejia’s criminal convictions occurred before the November 2014 passage of Proposition 47 and were too serious to have been affected by the law, which downgraded some drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors.

Nor was Mejia affected by AB 109, Jeffrey Callison, a spokesman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said in a statement.

Mejia “was not released from state prison early” and “served his full state prison terms as defined by law,” Callison said.

However, Callison noted that because of AB 109, Mejia’s release was supervised by Los Angeles County probation officials rather than state prison officials.

Prompted by a federal court order to reduce prison overcrowding, Gov. Jerry Brown in 2011 spearheaded AB 109, a massive shift of inmates from state prisons to county jails. The measure also allowed some inmates to serve a “split sentence,” with part of the time on probation instead of behind bars.

Magnus Lofstrom, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, co-authored a 2016 study concluding that AB 109 had little effect on the percentage of former inmates who committed another crime. Recidivism rates for California remained high after AB 109 — nearly 70% had reoffended at the two-year mark.

The measure did not cause an increase in violent crimes through 2014, though auto thefts rose, the report said.

In an interview, Lofstrom said a financial cost-benefit analysis favors AB 109, since the $60,000 annual price tag of incarcerating someone is higher than the societal cost of an auto theft.

There is still no evidence that AB 109 caused an increase in violent crime, Lofstrom said. But he acknowledged that when the lives of potential victims are at stake, discussing costs and benefits is uncomfortable.

“Talking about the trade-offs of seeing more violent crime, versus cost savings, is a very challenging discussion to have,” Lofstrom said.

Lenore Anderson, executive director of Californians for Safety and Justice and an author of Proposition 47, said some criminals cycled in and out of prison well before the recent reforms.

The solutions, which have yet to be implemented in many places, include more rehabilitation for offenders as well as punishments that are geared toward an individual’s risk of committing another crime, Anderson said.

“We’ve had a criminal justice system that’s had a revolving door problem for decades,” Anderson said. “This is the fundamental problem with how criminal justice has been functioning, which is a one-size-fits-all response, in which people are worse when they’re released as opposed to rehabilitated or able to be productive in society.”

In July 2016, three months after Mejia returned from Pelican Bay, he committed his first probation violation. He received 10 days in jail — what is known as a “flash incarceration,” intended to deliver an intense but relatively short punishment.

He violated his probation again in September, then again in January, serving short jail stints each time.

Most recently, he was arrested Feb. 2 after someone called 911 and Mejia ran from sheriff’s deputies. He was released from jail Feb. 11, said Sheriff’s Homicide Lt. John Corina.

One of Mejia’s probation violations occurred when he was caught with a small amount of methamphetamine, said Corina, who described Mejia as “a hardcore gang member.”

Terri McDonald, head of the L.A. County Probation Department, confirmed that Mejia was under her department’s supervision, but she declined to discuss his case, because it is being investigated both criminally and by probation officials.

The probation department “will conduct a comprehensive post-incident review,” she said.

Mejia’s grandfather, Lino Mejia, said the younger man had been staying at his East L.A. home since returning from prison.

Mejia struggled with meth addiction and had been using again since his release, Lino Mejia said.

Lino Mejia said he called his grandson’s probation officer several times to report the drug abuse, most recently on Feb. 15. When he last saw his grandson Saturday, two days before the deadly shooting, Michael Mejia appeared to be high.

Lino Mejia shook his head in disgust when asked about the slain officer.

I feel like it was our fault. Maybe we spoiled him.

— Lino Mejia, suspect’s grandfather

“I feel like it was our fault,” he said. “Maybe we spoiled him.”

Lino Mejia has been a victim of his grandson’s crimes. In 2013, Michael Mejia stole the family’s car, according to court records. Mejia was convicted of grand theft auto and attempted vehicle theft — the crimes that sent him to Pelican Bay. Prosecutors sought a four-year sentence, but the judge gave him two years.

On Monday morning, Mejia is suspected of fatally gunning down his 46-year-old cousin, Roy Torres, in East L.A. Torres, who had one son, had moved in with his parents two years ago to take care of his ailing father, said a relative, Gina Gomez.

“He was a loving family member, a devoted son and father,” said Gomez, who declined to speak about Mejia or the shooting.

After killing his cousin, authorities said, Mejia allegedly drove away in the stolen car, ending up in Whittier, where he rear-ended another car. As Mejia and the other driver were moving the vehicles to the side of the road, Boyer and Officer Patrick Hazell approached.

Mejia shot at the officers, who returned fire, authorities said. Hazell, a young officer with three years on the force, was injured, as was Mejia.

Boyer, 53,who had two adult sons and played drums in a classic-rock tribute band, died at a hospital.

Times staff writer Maya Lau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @cindychangLA

Twitter: @LAcrimes

Twitter: @JamesQueallyLAT

ALSO

Gang member accused of killing Whittier cop had cycled in and out of jail, records show

Gunman who killed Whittier officer had fatally shot cousin hours earlier, police say

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.