How Asian Americans climbed the ranks and changed the political landscape

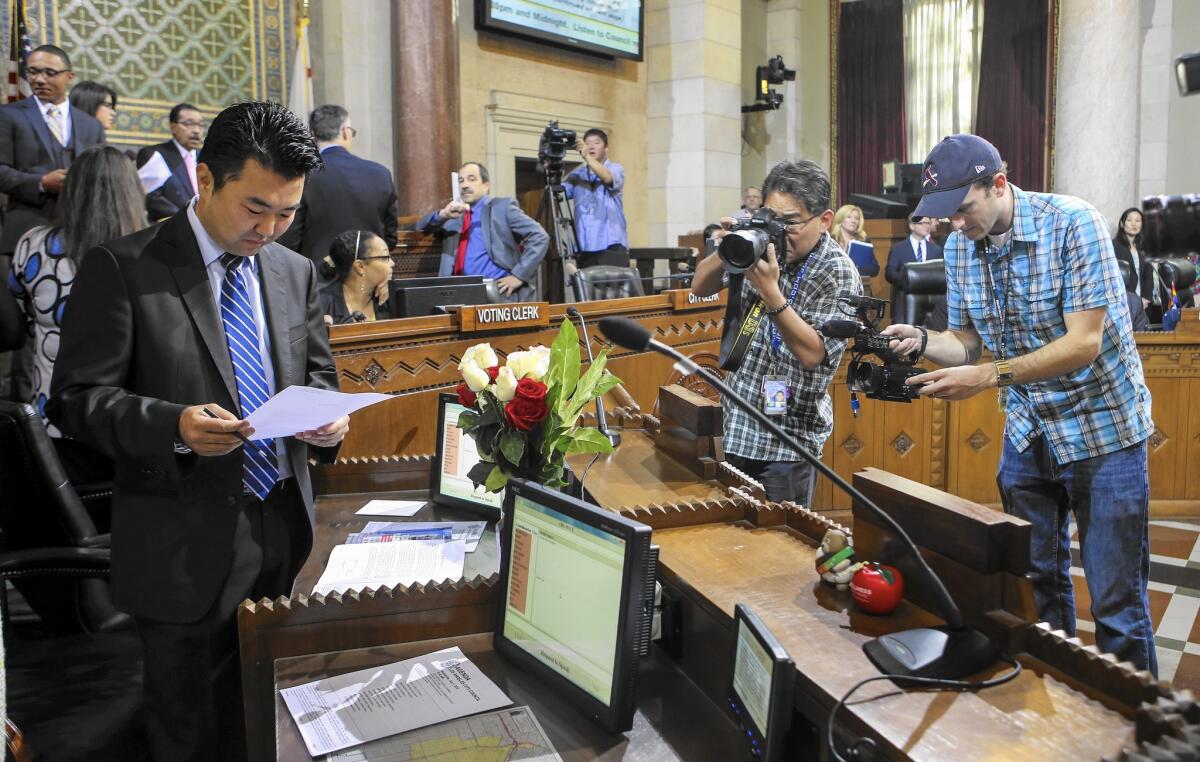

L.A. City Councilman David Ryu, left, entered politics in 2003 as a deputy to L.A. County Supervisor Yvonne Burke. “It was just inevitable that elected officials wanted to build that bridge, and they hired deputies that looked like those communities,” he said.

- Share via

Steve S. Kim had been running a flower shop with his sister across the street from Los Angeles City Hall for a couple years when a customer who bought flowers every week for his wife off-handedly asked a life-changing question.

A year earlier, riots had torn through Los Angeles. The new mayor, Richard Riordan, was amassing a diverse staff. Did Kim have any interest in politics?

Kim, who was 25 at the time, figured: Politics? Why not?

NEWSLETTER: Get essential California headlines delivered daily >>

The customer set up an interview with Riordan’s chief of staff, who turned out to be a fellow alumnus of John Marshall High School.

Soon, instead of delivering flowers weekly for the City Hall rotunda, Kim took on a new role as liaison between the mayor’s office and the Korean American community — no matter that he barely spoke Korean.

Kim quickly realized he was one of only a handful of Asian American political deputies working in City Hall and one of just two Koreans.

In the 23 years since then, the political landscape has changed. The number of Asian Americans seizing opportunities to work on the staff of elected officials at local, state and federal levels has expanded dramatically. And from the ranks of those who, like Kim, started out working for white or African American politicians, a cadre of Asian American political leaders has emerged.

Over the same period, Asian Americans have become the fastest-growing population across the U.S., particularly in Southern California, where they are increasingly influential as business leaders, voters and political donors.

“It was just inevitable that elected officials wanted to build that bridge, and they hired deputies that looked like those communities,” L.A. City Councilman David Ryu says.

Ryu made his foray into politics in 2003 as a deputy on the staff of then-L.A. County Supervisor Yvonne Burke. His job was to keep his boss informed about what was important to Asian Americans while helping constituents navigate the linguistic and bureaucratic labyrinth of local government.

His work helped the supervisor’s constituents, and the experience helped him.

Asian American staffers who had paved the way before him offered on-the-job tips. They connected him to other political players. John Chiang, then a staffer for Sen. Barbara Boxer and now the state’s treasurer, sat him down for a talk about his career, Ryu recalls.

During his eight-year tenure with the supervisor in the mid-2000s, Ryu says he saw a surge in the number of Asian American community liaisons and legislative deputies.

“It was like a fad — everyone needed to have an Asian American on their staff,” he recalls. And for a long time, Asian American constituents seemed grateful just to have deputies who looked like them and understood their language. They never fathomed that they could vote one of their own into office, Ryu says.

The Asian Pacific American Legislative Staff Network, an informal group of Asian American and Pacific Islander political deputies that began shortly after the riots, estimates that today there are between 50 and 60 aides working for officials in the Los Angeles area.

I thought I’d never see a Korean council member in my time.

— Steve S. Kim

Thomas Wong, external affairs liaison for state Controller Betty Yee and an elected member of the San Gabriel Valley water board, sees the role of staffers as “helping connect the dots” for Asian Americans who might otherwise be neglected by public officials.

Lisa Thong worked on Chiang’s staff when he was state controller, and later worked for state Sen. Jack Scott. Having grown up in an immigrant family herself, she says she knew how important it was to connect new immigrants to public resources and help them navigate government bureaucracies. She saw it as her job to help people understand “what a senate office can and cannot do.”

When Assemblywoman Young Kim (R-Fullerton) began her two decades of working as a deputy to Rep. Ed Royce (R-Fullerton), fewer than a dozen people showed up at the legislative staff network’s meetings, she says. Now “there are Korean American staffers everywhere.”

These staffers still play a critical role as the “eyes and ears of the elected officials,” Kim says. And the job continues to springboard into office ambitious staffers such as Young Kim, who won her Assembly seat in 2014.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

After his break into politics in 1993, Steve Kim went on to work as a political aide for a city councilman, a state assemblyman and then a state senator. His Korean made strides along the way — and he has a tattered Korean-English dictionary to prove it. Today he is an independent land-use consultant helping businesses with permits and zoning.

Back then, Koreatown papers wrote about every Korean American deputy hired by elected officials as a major triumph.

Talking about the possibility of getting elected to office was a parlor game among staffers, who thought it wouldn’t become reality any time soon.

“It was a very nice thought, running, but nobody actually attempted it,” Kim recalled. “I thought I’d never see a Korean council member in my time.”

He’s glad to have been proven wrong.

Twitter: @vicjkim

ALSO

21 to smoke? California Assembly approves raising smoking age

Southern California air board moves to weaken pollution regulation

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.