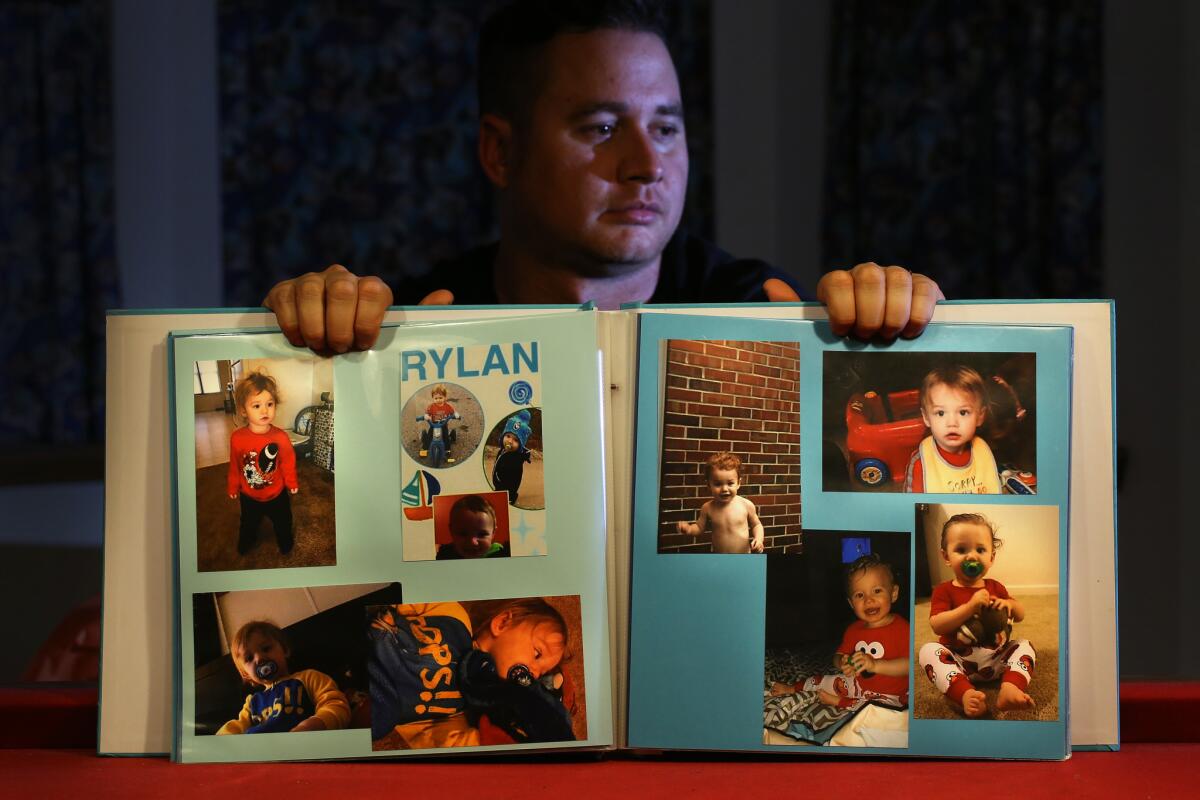

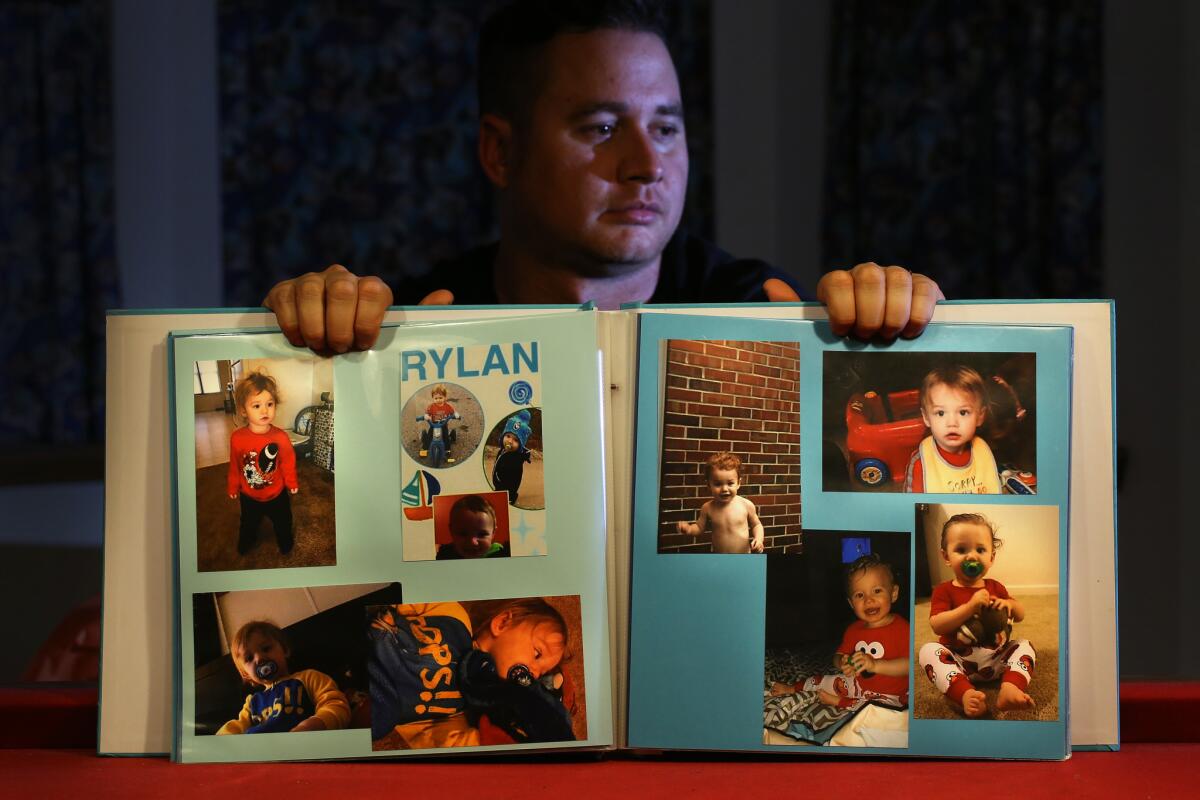

Child abuse in the military: The short, sad life of Rylan Ott

- Share via

Reporting from Ft. Bragg, N.C. — Police responding to gunfire at a mobile home near Ft. Bragg one night found a soldier in full military gear, waving an AR-15 assault rifle and trying to get a child to snort a powerful prescription tranquilizer.

Spc. Devin Havis and Samantha Bryant, his girlfriend, were abusing Klonopin and urging Bryant’s 13-year-old daughter, Brittany, “to engage in this drug use,” according to a police report from the October 2015 incident.

Officers found the girl hiding in a closet with her 17-month-old half-brother Rylan.

Police charged Havis and Bryant with child abuse and “fighting with firearms in the presence of minors.” Bryant was committed to a local hospital’s mental health ward for three days. The two children were placed in foster care at Ft. Bragg for their protection while military and civilian agencies investigated.

But America’s largest Army base — a heavily guarded enclave that is home to 238,000 soldiers and civilians — proved no refuge.

On April 14, four months after a state judge returned the two children to their mother, Rylan drowned in a pond near the mobile home.

Bryant was charged with involuntary manslaughter and child neglect and is in Moore County jail awaiting trial. Havis — who was not prosecuted on the earlier charges — was kicked out of the Army with a general discharge, one level below an honorable discharge.

Rylan’s death was one of at least five child fatalities or severe abuse and neglect cases at Ft. Bragg over the last 14 months.

Ft. Bragg officials declined to discuss the five cases, citing legal proceedings. But it’s clear, from court records and interviews, that the system failed toddler Rylan Ott.

His father, Spc. Corey Ott, had married Samantha Bryant in 2014, and their relationship was volatile.

“She liked to drink and party, and so did I, but when she drank, she got crazy,” Ott said in an interview.

She liked to drink and party, and so did I, but when she drank, she got crazy.

— Spc. Corey Ott

They lived in a cramped apartment on Ft. Bragg after Rylan was born, and then moved to an on-base house. Bryant’s daughter, Brittany, came from Texas to live with them.

But after Ott began an eight-month deployment to the United Arab Emirates, Bryant moved to a mobile home off base with the two children. She also began seeing Havis, a military policeman.

“She got my boy and my truck and just took off,” Ott said. “I felt like I was losing my family.”

When Ott returned in September 2015, Bryant refused to rejoin him. She showed him a new AR-15 rifle with a high-powered sight, saying she had bought it herself. Ott didn’t believe her, convinced that the weapon was proof she was seeing another soldier.

Bryant and Havis were arrested three weeks later for firing the AR-15 and sniffing Klonopin, an anti-seizure medication that is often abused, around her children.

Sgt. Shane Mills and his wife, Amanda, whose daughters attended school with Brittany, agreed to act as foster parents while the Moore County child protective services agency investigated the case.

Rylan was “real quiet” and very thin when he arrived on Nov. 2, Amanda Mills recalled. After a month, he had become a “sweet, smiling, laughing” little boy, she said.

The toddler’s mother was allowed to visit three times a week. But Bryant was so disruptive that the Mills asked authorities to halt the visits. After that, social workers drove the children to offices 25 miles away so Bryant could see them in supervised visits.

On Dec. 17, 2015, after a daylong hearing, North Carolina District Judge Scott C. Etheridge ordered Rylan and Brittany returned to their mother. He cited a state law that calls for courts to seek family reunification whenever possible.

The Moore County social services department backed the ruling, noting that Bryant had finished a class on parenting.

The judge rebuffed pleas from the foster parents and from Pamela Reed, a court-appointed social worker who had urged him not to send the children back to their mother.

The judge also rejected Ott’s request for custody, ruling he hadn’t spent enough time with the boy — mostly due to his long overseas deployment — to be a good father.

“I left that courthouse in tears,” recalled Ott, who quit the Army the next day.

When child protection workers arrived to take Rylan and Brittany to their mother, Shane and Amanda Mills also broke into tears, fearing for the children’s safety, they said.

“When this thing goes south — not if, but when — you call me, day or night,” Shane Mills said he told the social workers. “I will be there to pick up these children.”

The Mills never got a call. They learned Rylan had drowned when Brittany posted a photo on Instagram last April of the smiling toddler in her lap.

“RIP. This little boy is my little brother and he was really a blessing,” she wrote. “I love you Rylan Ott … but [you’re] with God now.”

Twitter: @davidcloudLAT

ALSO

Thousands of California soldiers forced to repay enlistment bonuses a decade after going to war

Defense secretary orders Pentagon to stop seeking repayment of California National Guard bonuses

Congress proposals would let California National Guard soldiers keep millions in bonuses

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.