Moms take on football, suing Pop Warner for their sons’ head trauma, deaths

Rancho Bernardo’s Jo Cornell has joined with another mom in a lawsuit against Pop Warner. Both of their sons were diagnosed with CTE after they died — one in a suicide and another in a crash.

- Share via

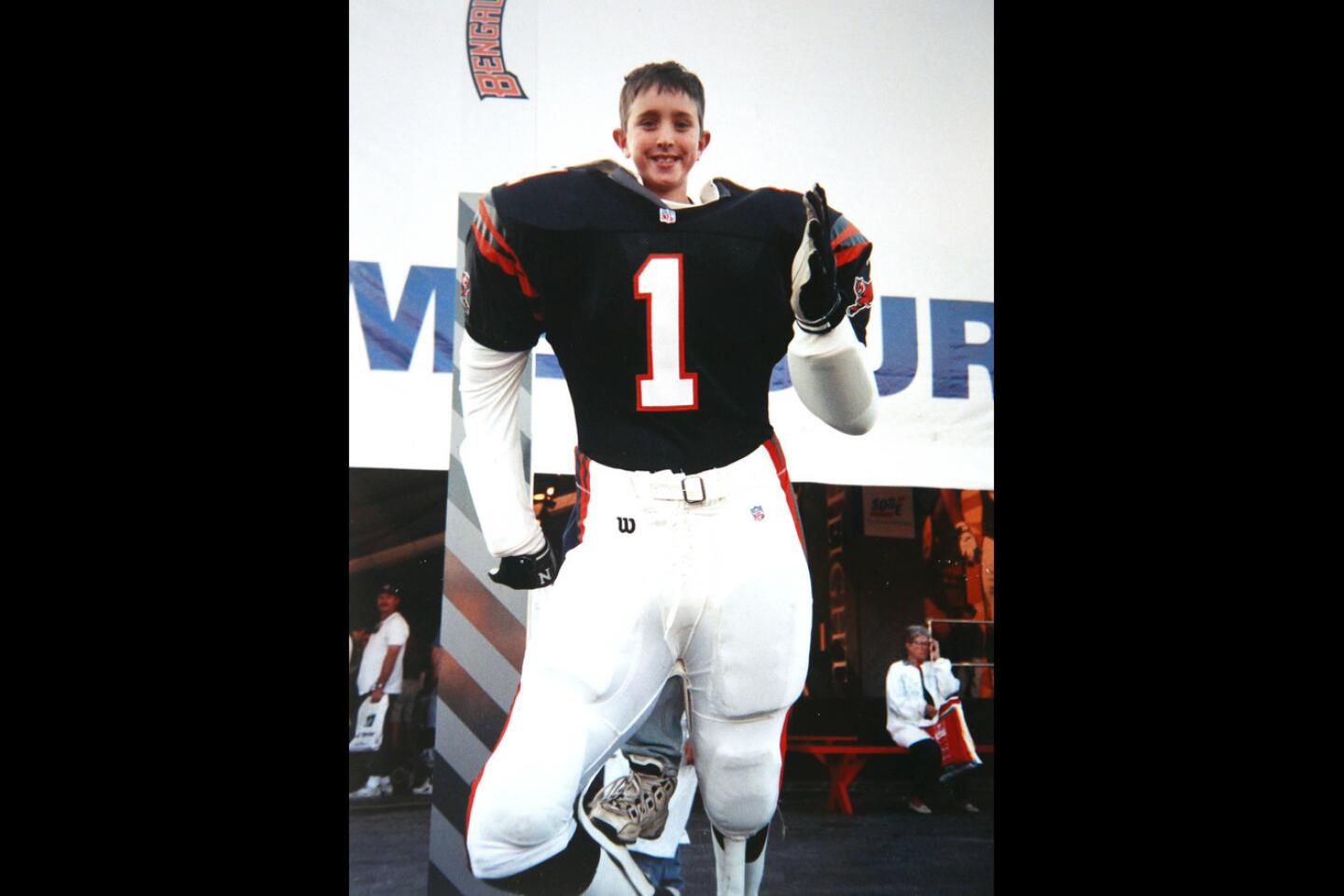

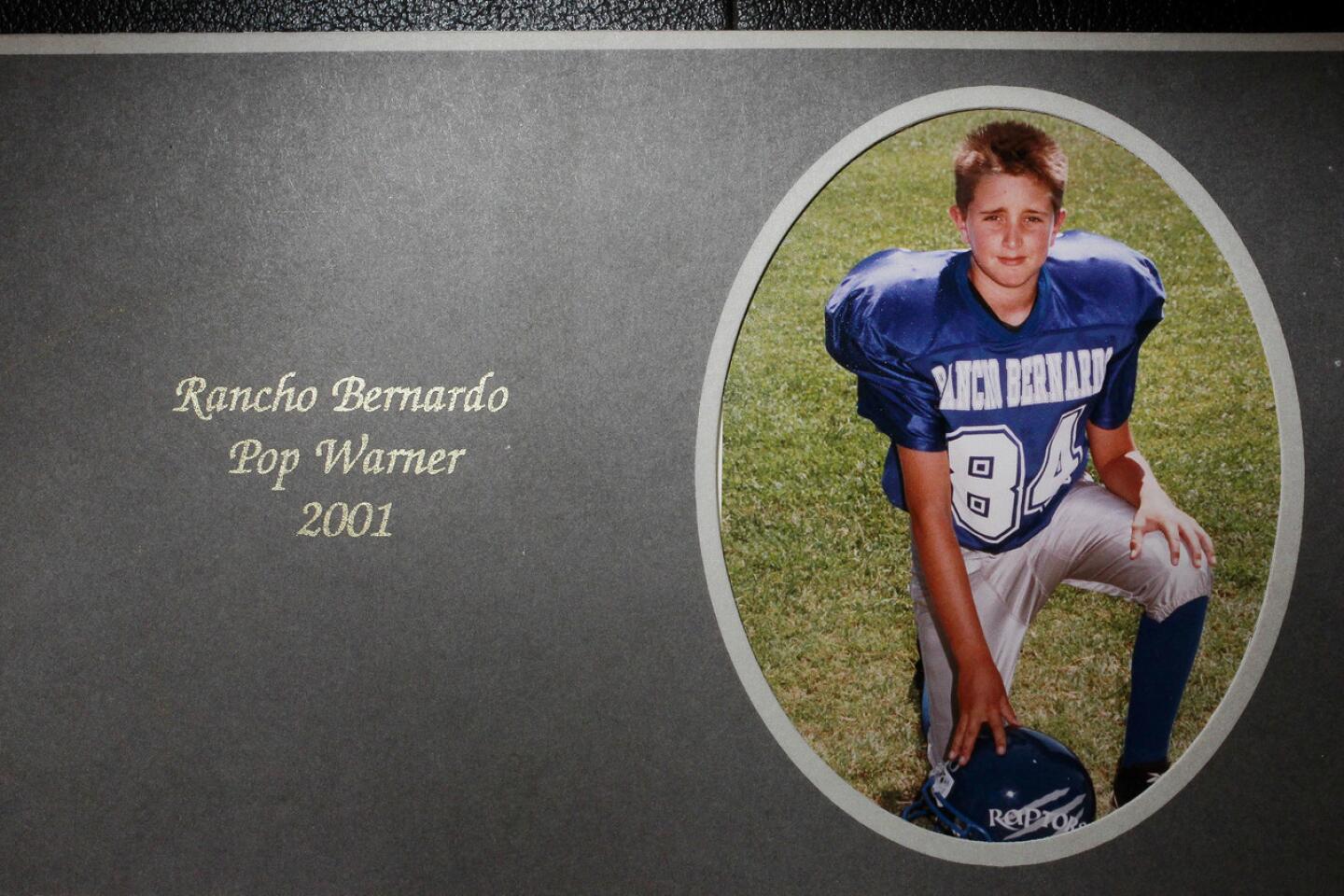

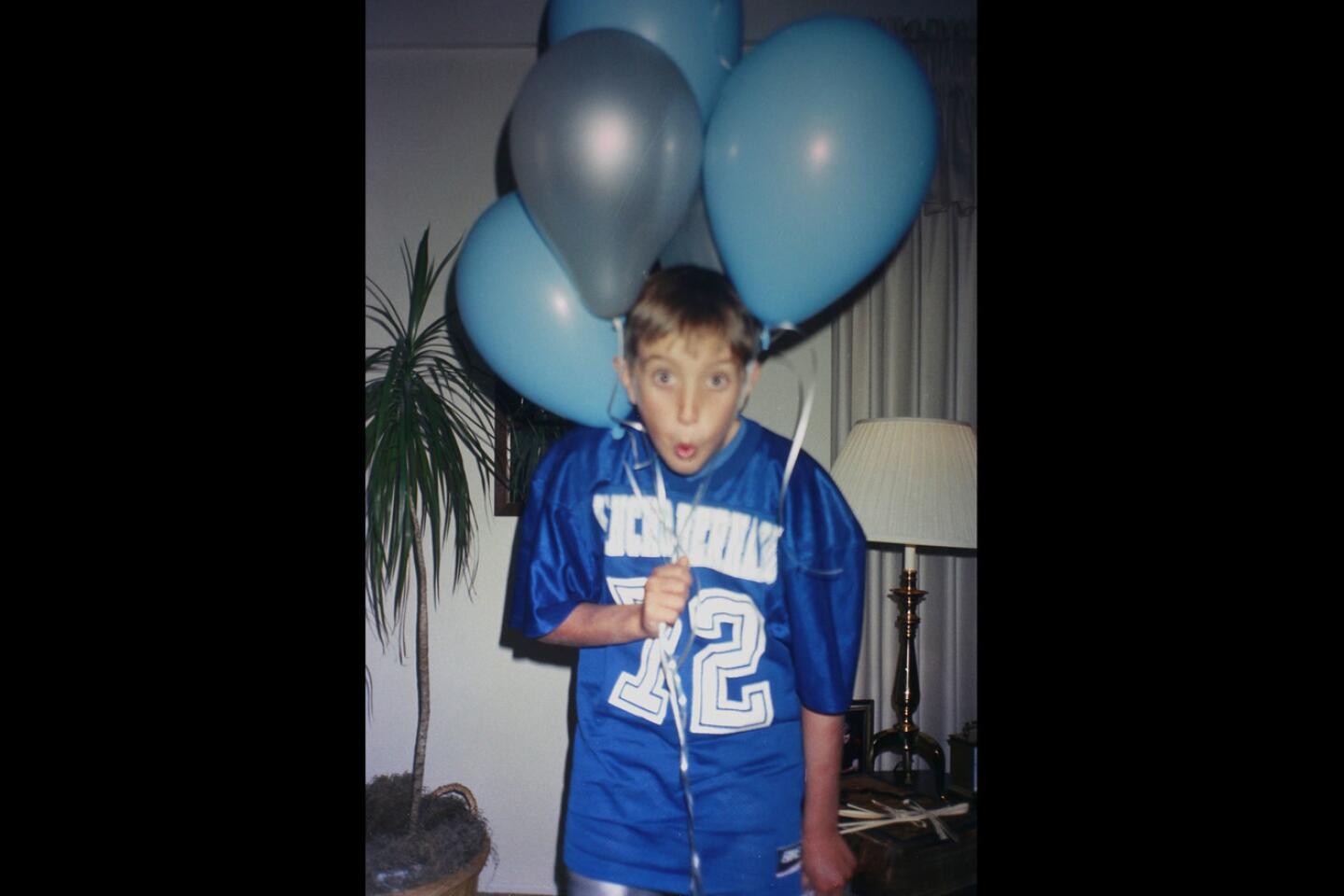

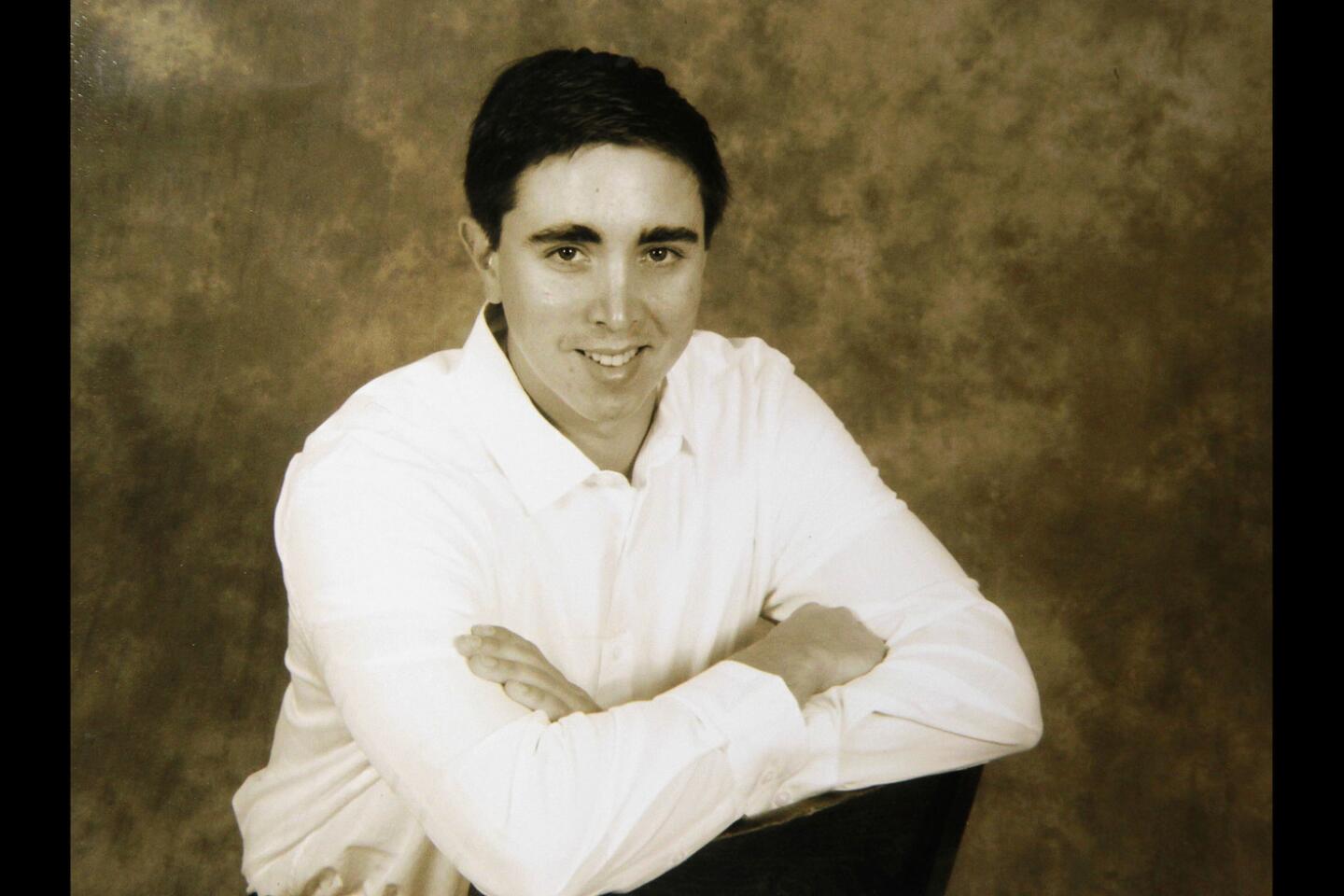

When the Rancho Bernardo Raptors went undefeated in the 2001 season and reached the Pop Warner Super Bowl in Orlando, Jo Cornell was behind the camera, recording interviews with the boys as they shared memories for a lifetime.

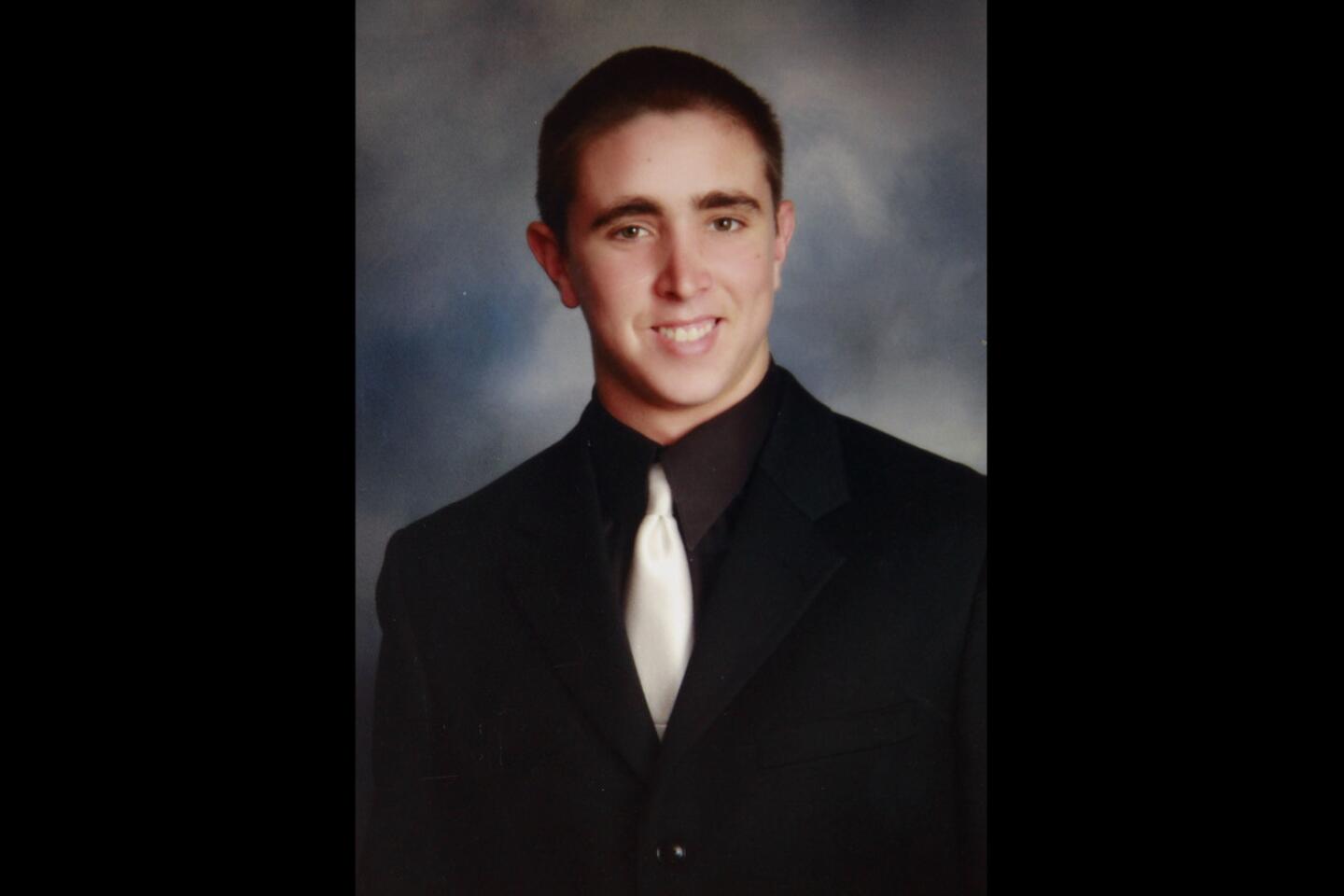

She loved that her son, Tyler, enjoyed success and found camaraderie in youth football, and later as an all-league lineman at Rancho Bernardo High.

Today, in the living room of her Rancho Bernardo home, Cornell hits the play button for those same DVDs, and she’s smiling wistfully one minute, teary the next.

Football was her only child’s first love, and she also believes it contributed to his death.

“You can’t un-know this stuff,” Cornell said.

At the age of 25, Tyler Cornell committed suicide in 2014 by shooting himself after seven years of waging a battle with mental illness.

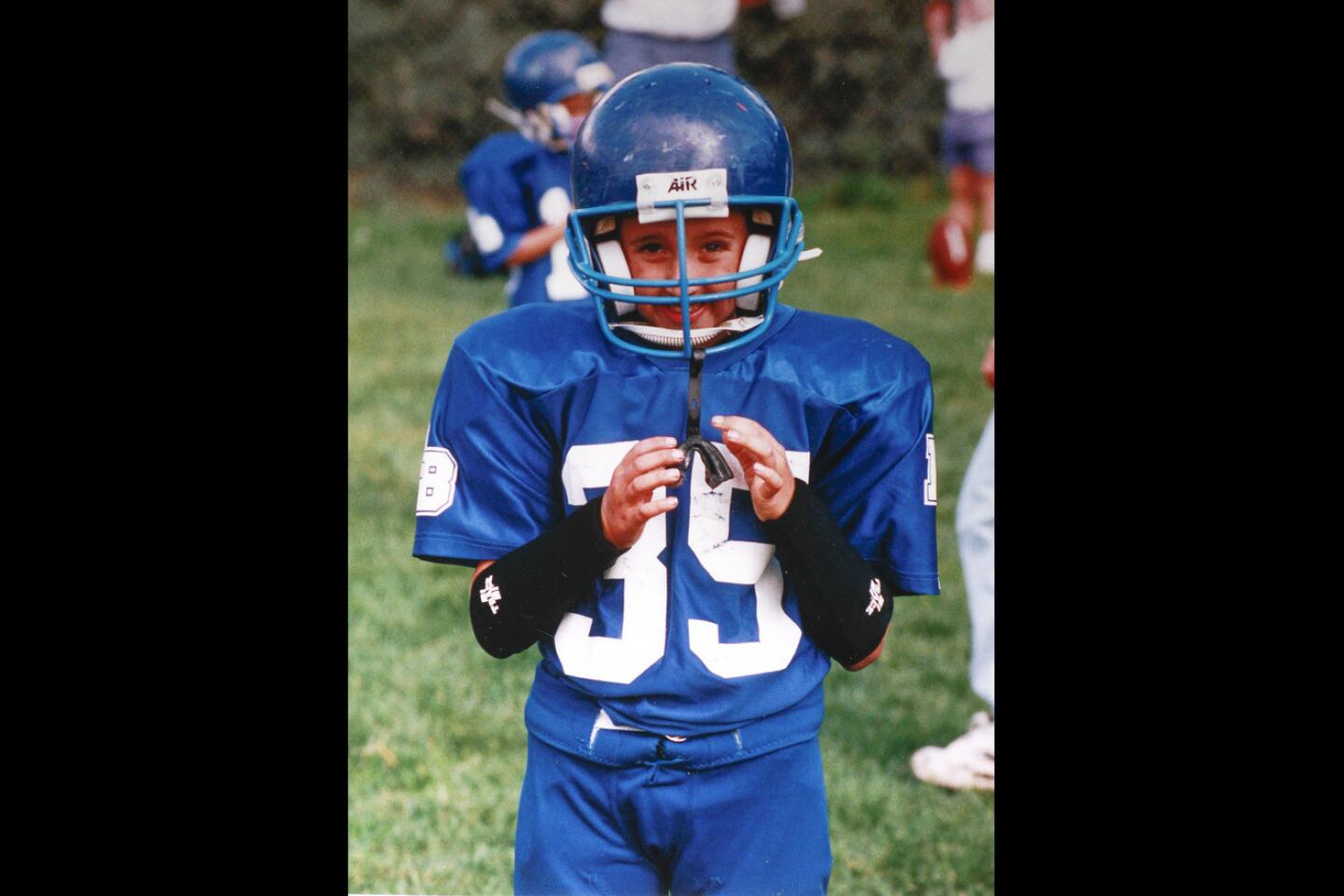

What Jo Cornell knew is that Tyler played football, mostly as a lineman, every year from the ages of 8 to 17. He suffered no diagnosed concussions, but took thousands of hits to his head in practices and games.

Soon after high school graduation, Tyler began suffering from severe anxiety and depression and was hospitalized numerous times.

Cornell heard the reports in the media about the brain condition that has plagued former football players — chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Suspicious about a link between football, and Tyler’s depression and suicide, she made the difficult decision to send his brain to Boston University, where the majority of CTE study has taken place.

The results came back months later, and Cornell’s fears were confirmed. Tyler had CTE.

“It was like experiencing another death,” Cornell said.

“This is something no parent should go through. There are widows and widowers, but there’s no word for a parent who has lost a child. It’s so awful they don’t even name it.”

Enveloped in what felt like bottomless grief, Cornell managed to move forward by finding a cause. She met up with another mom, Kimberly Archie, who understood her pain.

Archie’s son, Paul Bright Jr., died five months after Tyler, at the age of 24, when he revved his newly purchased motorcycle to 60 mph on a Los Angeles street and smashed into a car.

Bright played football from ages 7 to 14, and Archie, concerned about her son’s erratic behavior before his death, sent his brain to Boston University. It was confirmed he suffered from CTE.

The two boys are among the youngest to be diagnosed with a condition that doctors say leads to memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts and progressive dementia.

Big legal win

Cornell and Archie are among the most high-profile advocates for change in youth football in America, and beginning in 2016 they took the formidable path of suing Pop Warner, a national institution that has been around for 89 years.

The potential results could rattle the game.

Represented by Tom Girardi, the well-known L.A. lawyer who helped win the Erin Brockovich case, Cornell and Archie scored a significant legal victory in October.

Philip Gutierrez, a U.S. District Court judge in California, ruled that most of the claims in the case against Pop Warner Little Scholars, Inc. could move forward to trial, despite attempts by Pop Warner to have them dismissed.

Those claims: negligence, fraud, fraudulent concealment and negligent misrepresentation.

No case against Pop Warner has advanced this far in court. Other plaintiffs who sued PWLS in recent years eventually settled for undisclosed payouts.

“We have a very strong hand,” said Archie, of North Hollywood, who was an advocate for safety in youth sports years before her son died.

The moms are seeking unspecified damages. A trial date has not been set.

The opinions Gutierrez offered in his ruling likely sent shock waves through every level of organized football.

He concluded there was sufficient evidence supplied to support a link between playing Pop Warner football and brain injuries, and those injuries could be traced to the “acts or omissions by PWLS.”

The plaintiffs argued Pop Warner failed to implement league-wide guidelines for safety, failed to adopt equipment standards and failed to require brain injury history. The court agreed and said that by not instituting league-wide guidelines, PWLS “increased the risk of head injury to players.”

Gutierrez also concluded the plaintiffs produced sufficient facts that Pop Warner misrepresented its safety protocols. The judge noted PWLS states on its website that “the safety of our athletes is always top priority,” and that extensive training was provided for all coaches. Gutierrez countered, “Pop Warner does not in fact ensure coaches receive training at all.”

Pop Warner administrators at the national home office in Langhorne, Pa., did not return messages seeking comment for this story.

In 2012 — years after Tyler Cornell and Paul Bright stopped playing youth football — Pop Warner enacted new rules intended to limit contact in practice. Players could no longer run full speed at each other in blocking and tackling drills, and contact was limited to one-third of the total practice time.

Pop Warner also teamed up with USA Football’s “Heads Up Football” program in an attempt to teach better tackling.

“I think football is safer than it’s ever been,” Paul Watkins said in an interview in October. He is the Phoenix-based director for Pop Warner’s Wescon Region, which includes San Diego.

Cornell contends that Pop Warner is more interested in signing up kids and taking their fees than it is about safety.

“It’s still a bitter pill,” she said. “It’s very hard to fathom a company, a 501(c)(3) that is supposed to benefit children in their care, be so careless with their brains.

“There were good things about Pop Warner. They stressed academics and wanted kids to be scholar-athletes. But, for football, it’s too high of a price to pay. If I knew then what other moms know now, why risk it?

“There’s no gain. Sitting on a lawn chair at the community park isn’t worth it.”

Archie put it even more bluntly: “Every parent in America needs to know that they’re playing Russian roulette with their kid’s brain. If they’re letting their kid play Pop Warner, they are knowingly taking the risk.”

Faces of CTE

Archie has done far more than talk about the issues. With other women whose family members suffered from CTE — including Mary Seau, the sister of Junior Seau, who committed suicide in 2012 and was found to have CTE — Archie started an organization, Faces of CTE, to raise awareness and increase brain donations to benefit further study.

On the Faces website, there are profiles of football players of all ages who were diagnosed with CTE after their death. They range from boys who never played in college to superstars such as Seau and Ken Stabler.

The Faces group initiated “National CTE Awareness Day” on Jan. 30, 2017, and met in Houston when the Super Bowl was being played there.

This year, the office of California State Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher worked to have the state assembly recognize Jan. 30 as “CTE Awareness Day” in California.

The Faces of CTE site also promotes “Flag ’Til 14” — urging parents and administrators to not allow kids to play tackle until they are in high school.

Archie would like to see it become law, noting that there are legal ages for driving, smoking, joining the military — “and any other thing that has been deemed a dangerous activity.”

Children can start playing Pop Warner tackle at 5 years old and 35 pounds.

“So they’re riding to the game in a car seat, and there are all kinds of regulations for that,” Archie said. “But once they get on the football field, they’re playing in these ‘Lego’ helmets that haven’t even been certified for safety.”

Promoting flag is a way for Archie to support the game without advocating tackle football.

“We wanted to be proactive and have a positive presence,” she said, “rather than just saying, ‘screw football, our kids are dead’ — which wasn’t going to get us very far.”

The idea of banning tackle at younger ages appears to be gaining momentum. This week, Carol Sente, a member of the Illinois House of Representatives, held a news conference to introduce a bill that would eliminate tackle football in the state for kids younger than 12.

Among Archie’s ideas for making football safer: sensors on helmets that follow hit counts; lighter and cooler helmets made of Kevlar instead of plastic (they have been developed by race helmet maker Bill Simpson); custom helmet liners; and guardian caps, a soft-shell helmet cover.

Archie fumes about the fact that children’s football helmets weigh only a few ounces less than adult helmets, because kids don’t have the neck, shoulder and chest structure to use them properly. And because the temperature inside the helmet can be 15 to 30 degrees warmer, she dismissively calls them “shake and bake.”

Archie’s no-holds-barred attitude has earned her some high-profile fans.

Soon after her son died, she was speaking at a conference in San Diego, and a gentleman near the front seemed enthralled by what she was saying. She would later be seated next to him at dinner. It was Mike Haynes, the Hall of Fame cornerback from the Oakland Raiders.

The two have been friends ever since, and Haynes has been an ardent supporter of Archie’s causes.

“I understand their concerns,” Haynes, a San Diego resident, said in a phone interview. “If you’re close to youth football, you have a better understanding and see why they’re on a mission to make a difference.

“Most people are just uneducated about it. They’re letting their sons play football because they love football. They’re not asking about the results of impact on their son, or how do you train, or how often do you hit?”

Haynes, 64, whose mother didn’t let him play football until high school, has boys of his own who have played, including Tate Haynes, a Cathedral Catholic High grad and quarterback who is a freshman at Boston College.

Mike Haynes said he closely monitored how his son practiced throughout youth football. While they lived in Connecticut, he said he coached and adopted the philosophy of another coach who didn’t allow tackling at all in practice.

“It’s different in California,” Haynes said. “They treat it like the NFL.”

Dealing with loss

Jo Cornell, who has worked 25 years as a paralegal, doesn’t travel in circles with famous people. She isn’t on social media, and never imagined that she would have to share a story of such loss.

She hadn’t spoken much about Tyler’s death until now.

“To do this in a very public way, this is the worst story ever,” Cornell said. “This isn’t Tyler at his best. This is the worst, most tragic thing that could happen to a person, let alone my son. It’s a private hell.”

After Tyler’s death, his mom suffered dark thoughts about all of the struggles — the psychiatrists, the medication, the hospital stays.

That cloud has lifted to a large degree, and Cornell said she can appreciate the strength and dignity he showed in the fight.

She can now warmly recall a kid who she thought of as “Bambi” for his gangly strides on the football field, someone who she said was a warm, sensitive kid who deeply valued his friends and asked to visit Father Joe’s Villages to feed the homeless.

Tyler did well in school and decided to attend UC Santa Barbara with friends. He wasn’t there long, suffering a breakdown in his sophomore year when he learned of the death in a car accident of a former Raptors teammate.

When Tyler got better, he enrolled at UC San Diego and was selected to be in an honors fraternity.

But anxiety and depression dogged him, and even when the family made a trip to Ann Arbor, Mich., to see Michigan, his favorite football team, play, his mom said Tyler wasn’t happy.

“He was probably the only person in the stadium wearing black when everybody else was wearing maize and blue,” Cornell said.

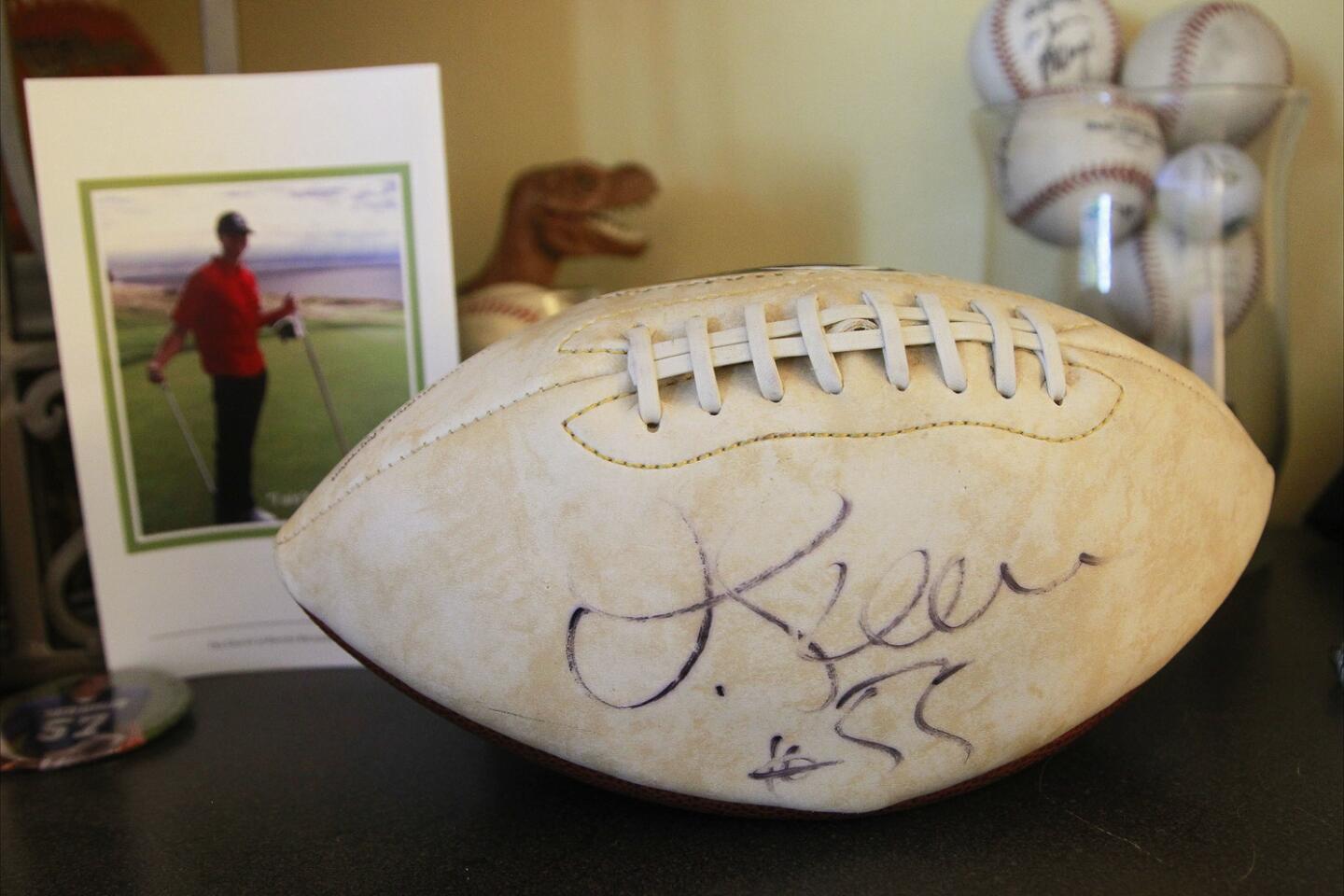

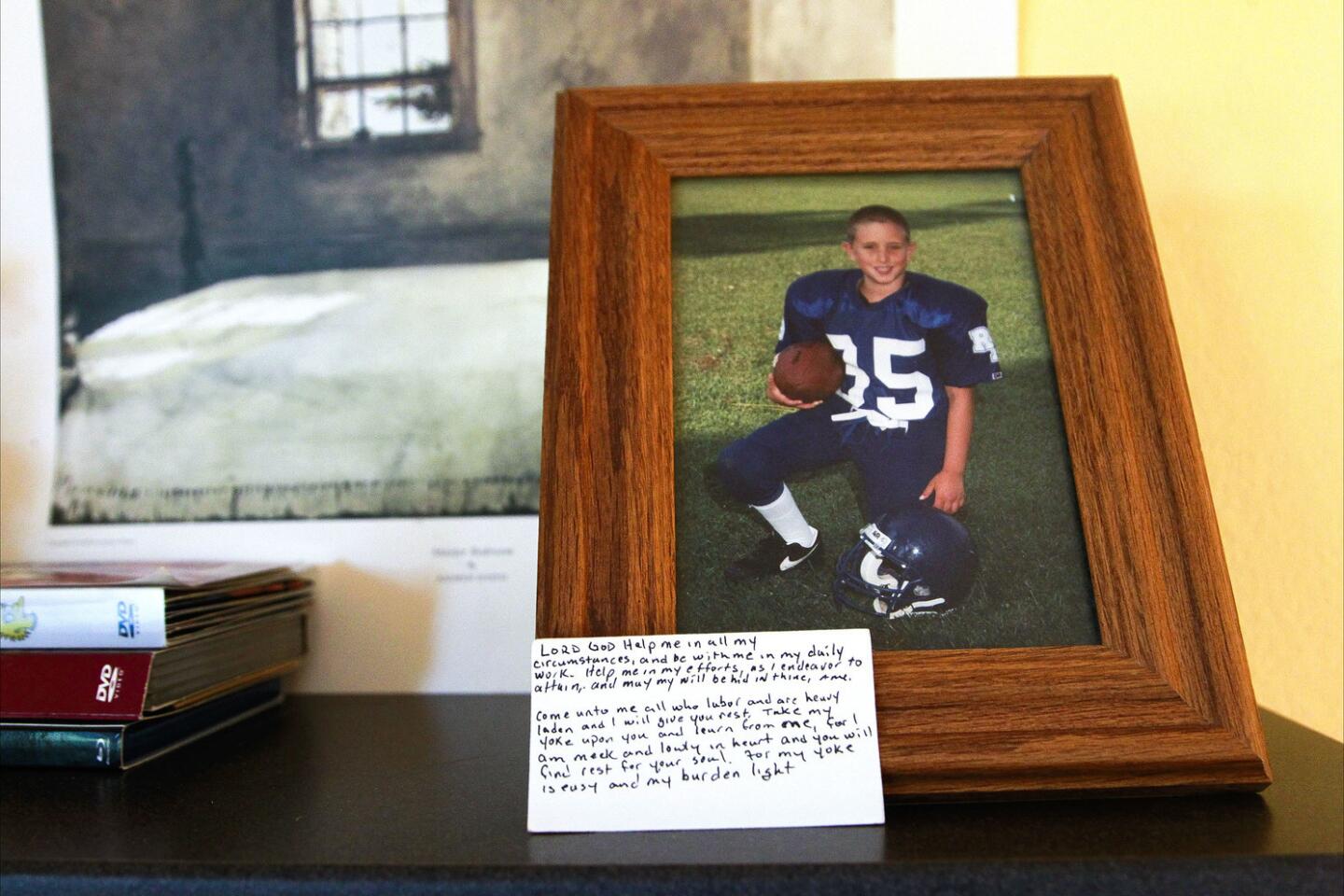

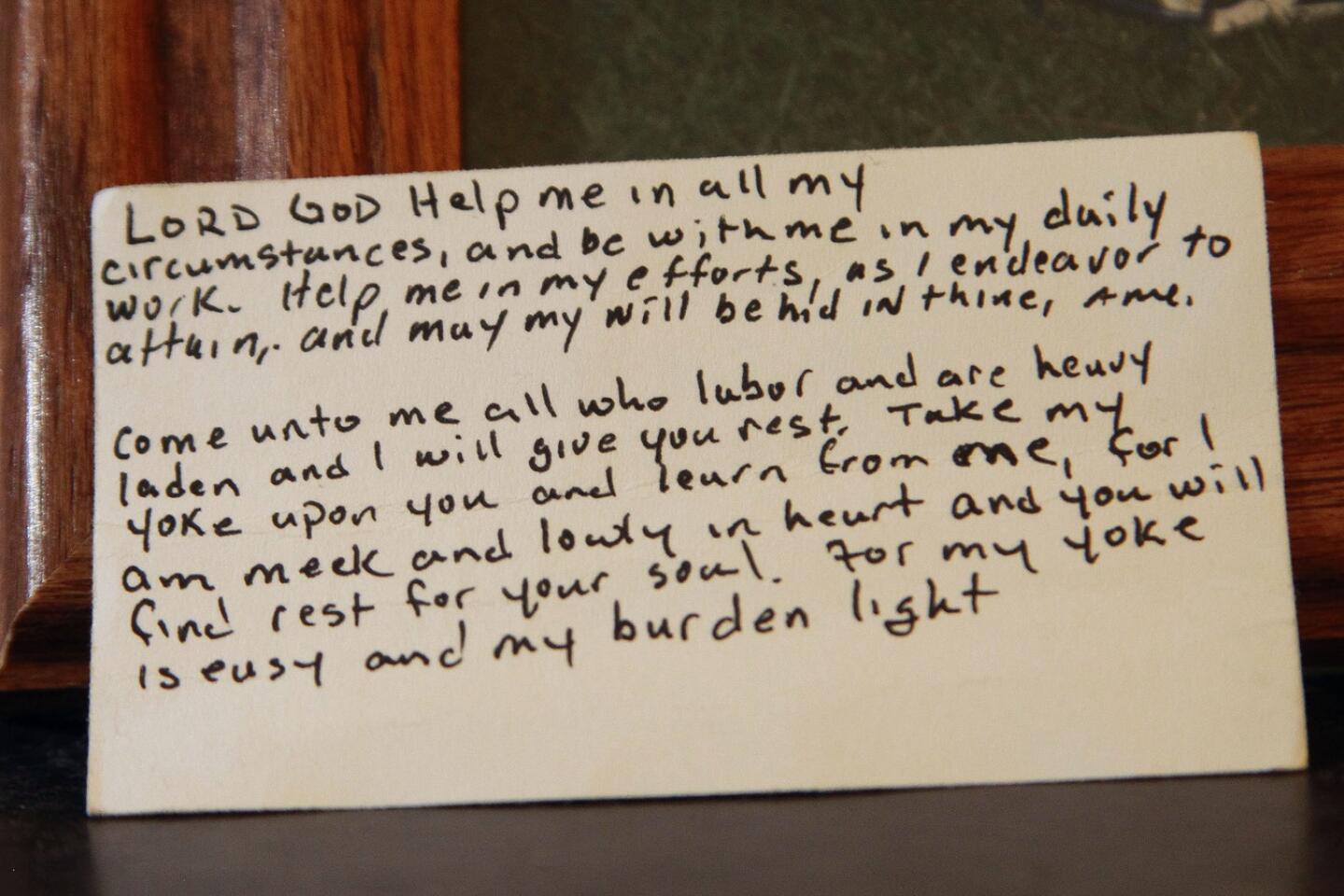

Cornell has kept Tyler’s room very close to how he left it on his final day. Poignantly, there’s a flat football with a faded autograph: J Seau #55. Trophies abound, and one catches the eye. It’s tall and silver, the prize for the regional championship on the undefeated 2001 Raptors team.

Draped around the player’s neck on the trophy are three bracelets made of plastic beads. They represent Tyler’s low points, when doing crafts was a way to pass the hours while he was under psychiatric observation.

Cornell pointed out that one of the bracelets included beads shaped like footballs.

“That one gets me every time,” she said, her voice wavering.

“It’s heartbreaking to think,” she continued. “Here’s my 24-year-old son. He’s bright, and he was doing wonderful things when he was on track. And now he’s making these in a mental ward.”

On a warm spring morning in April 2014, Tyler went for a walk around the neighborhood with his mom and then told her was heading off early to his first class of the quarter at UCSD. He left her with a sing-song “Love-you-mom” goodbye.

He didn’t go to school, but instead drove two hours to his grandparents’ home in West Covina. A caretaker let him in and Tyler went straight to the gun he knew was in the house. He shot and killed himself.

“Only Tyler knew what he was living with,” Cornell said. “We think he was too kind and never showed how deep his lows were, just to spare us.”

In her sorrow, Cornell had this thought: “Tyler was sucker punched.”

Cornell has found solace at her church and in groups with other parents who have lost their children.

“What I tell people is that you have to do what works for you. Any given day or time, that’s your reality,” Cornell said. “Be gentle with yourself. I don’t think everybody is meant to carry a torch.”

Cornell is getting her message out, mom-by-mom, mom-to-mom. If she’s standing in line at a store next to a mother with a young boy, and the vibe is right, she’ll ask if she can tell her the story about Tyler, football and CTE.

“It’s coming from my heart, to give this information,” Cornell said. “I’d stop talking if a wall went up. That hasn’t happened yet.

“Awareness is the goal,” she said. “That’s the beauty from the ashes.”

Sports Videos

tod.leonard@sduniontribune.com; Twitter: @sdutleonard

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.