Editorial: NRA-backed restrictions on compiling gun sales records need to change

- Share via

When police recover a gun from a crime scene, they usually check with the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to determine the weapon’s history — who made it, who bought it from whom and when. But because of ludicrous restrictions that Congress has placed on the agency, a gun trace that should take minutes instead takes days, wasting precious time and millions of taxpayer dollars.

The problem is rooted in the gun lobby’s fear that the federal government might someday use a national database of gun ownership to embark on a campaign of firearm confiscation. That is at best paranoia, since the information is available to investigators anyway. It just takes time to access it — time that could be better spent solving crimes.

Federal law requires people engaged in the business of selling firearms to obtain a license from the ATF. It also requires those gun dealers (139,840 all told in 2015) to maintain records of their transactions and make them available to the federal government when requested. The Obama administration is expanding the definition of who must comply with those rules in an effort to close the so-called “gun show” loophole, in which private dealers claim they are hobbyists merely selling off pieces of their personal collections, and thus not required to obtain licenses, seek background checks on buyers or maintain records. The new rules would make such sellers abide by the reporting standards.

Notably, those sales records remain with the sellers and are not compiled by the federal government. Which means that when local law enforcement agencies seek a gun trace — something they do about 373,000 times each year, or more than 1,000 times a day – from the ATF’s National Tracing Center in West Virginia, federal agents send identifying details to the manufacturers, who determine the dealer to whom it shipped the weapon. The investigators then contact the dealer, and continue on down the chain of possession until they find the last legally recorded owner of the gun. Most traces take up to a week to complete, and according to a recent Government Accountability Office report, about 70% of the traces successfully identified a dealer or buyer for the weapon (though that wasn’t necessarily someone involved in the crime).

Such traces offer police an avenue of investigation, but it’s a woefully slow and cumbersome system — just the way the NRA wants it. And the absurdity is heightened when you look at what happens to the dealers’ records when they go out of business. Under the law, those sales records go to the ATF, which is barred from entering them into a single searchable database. The Government Accountability Office’s probe criticized the ATF for copying the records into one electronic collection, in violation of the Congressional restriction; ATF deleted the collection by the time the GAO’s report was released. So how do the investigators search the records they possess? By hand, locating the paperwork from the relevant dealer and then combing through the boxes or microfilms in chronological order until they find the right sales record.

There are very real privacy concerns to weigh before letting the federal government build databases of information concerning private citizens. But when it comes to firearms sales, the public’s interest in safety and law enforcement is paramount. Besides, individual privacy can still be protected through such steps as limiting gun traces to firearms involved in a criminal investigation and barring fishing expeditions.

The U.S. Supreme Court misread the 2nd Amendment when it ruled in the 2008 Heller decision that individuals have a right to own a firearm in their home for self-protection, but that same decision correctly held that government has an interest in regulating firearms. That includes creating record-keeping systems through which to monitor compliance and determine who the bad actors might be among gun dealers (some are disproportionately the sources of guns used in crimes, which can suggest failure to properly follow gun-sale regulations).

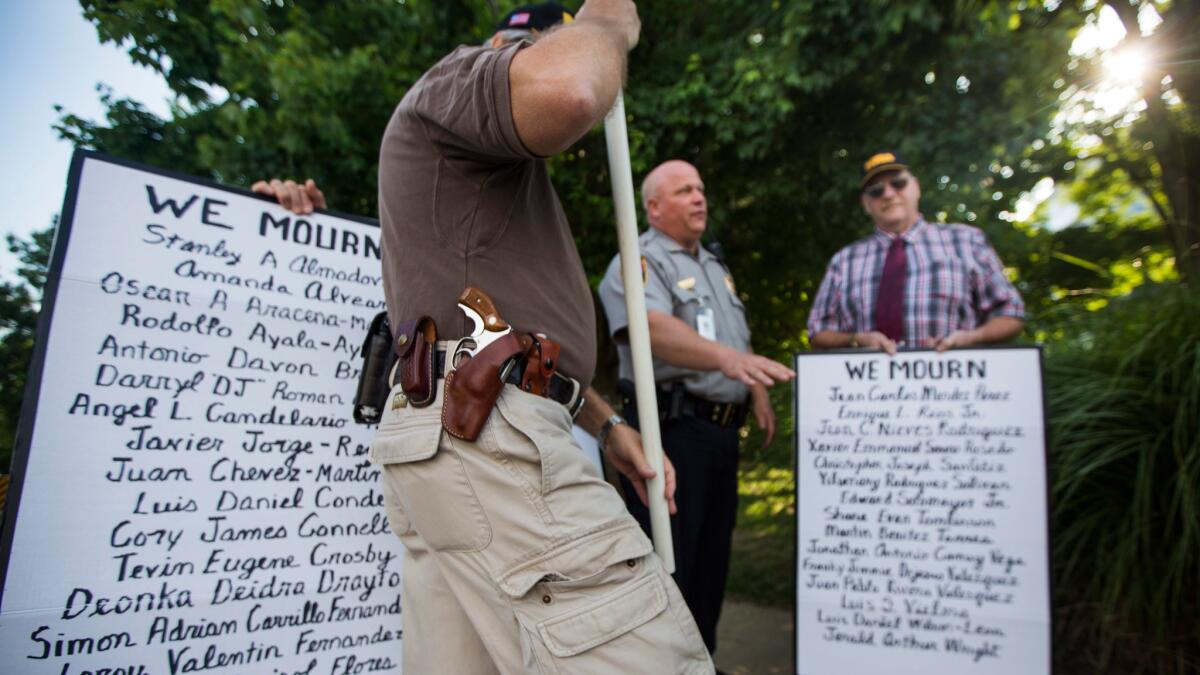

The nation is awash in guns, and we outpace our peer countries by an obscene amount when it comes to gun homicides. Congress’s limitations on the ATF collecting gun sale data and compiling it into a usable form are not only wrong-headed, they are yet another area in which the gun lobby has managed to pervert the system to put the interests of zealots ahead of public safety. Lawmakers should fix that.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.