Editorial: GOP takes on the FCC over net neutrality

- Share via

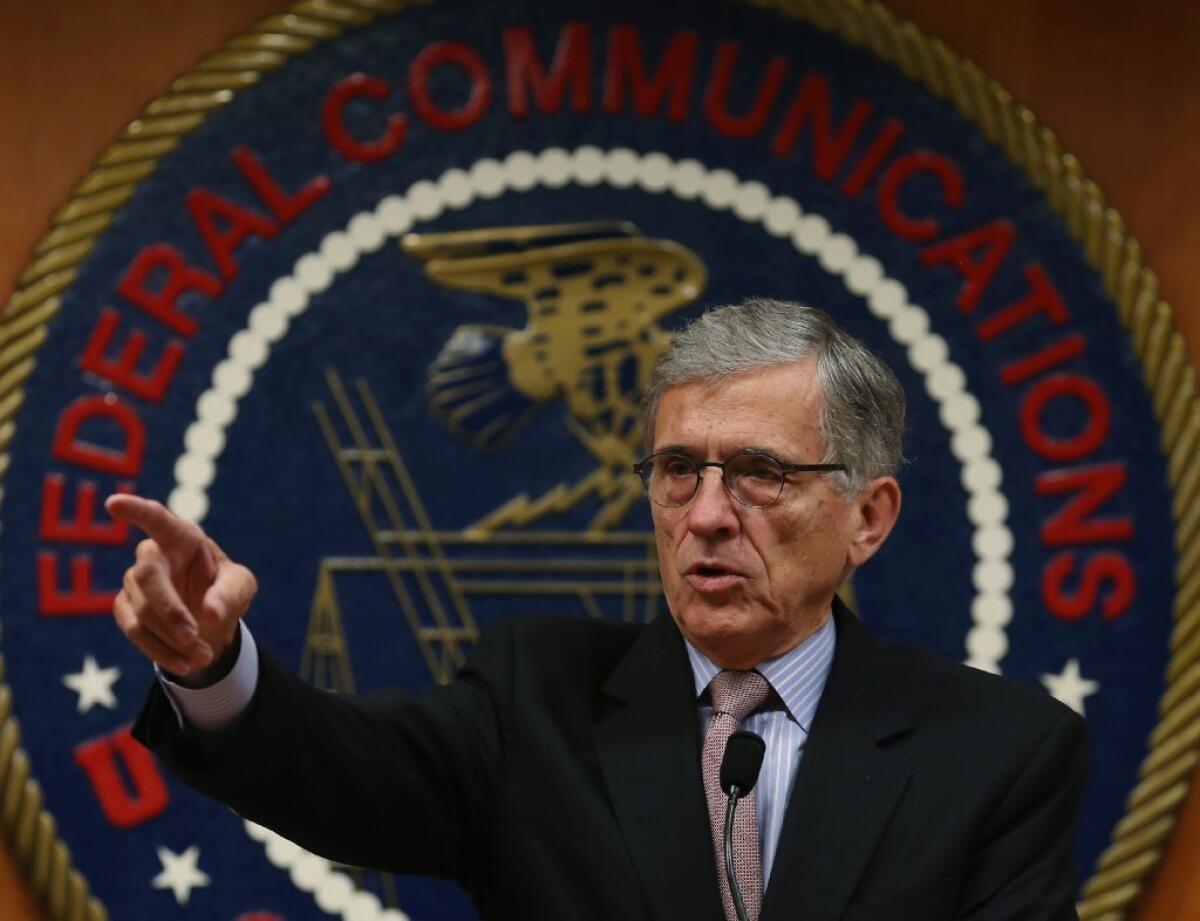

Many congressional Republicans were outraged when Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler announced a new net neutrality proposal this month that was considerably tougher on the cable and telephone companies that provide Internet access than the plan he’d unveiled in April. They were particularly upset that Wheeler’s shift gave President Obama everything he asked for in November, when he called on the FCC to adopt “the strongest possible rules to protect net neutrality.” Republicans were so upset, in fact, that they launched inquiries on whether the president improperly meddled with an independent agency.

Not to meddle in congressional affairs, but they’re wasting their time.

Congress created independent agencies such as the FCC to craft and enforce regulations without being subject to the dictates of whoever happens to occupy the White House. To keep the agencies’ governing bodies free from undue influence or fear of presidential reprisal, members serve fixed terms that don’t necessarily coincide with the president’s, and they can be kicked off only for reasons specified in statute.

Even so, the agencies aren’t exactly insulated from the White House — or from Congress, for that matter. The Supreme Court ruled in 1976 that the agencies’ governing bodies had to be filled by presidential appointment, ensuring that they would be led by people aligned with the party in power. Congress often requires appointees from both sides of the aisle, but in the FCC’s case, three of the five commissioners picked by the president are in his own party.

Over the years, presidents have regularly offered these agencies their views on proposed rules and policies. In fact, since the Clinton administration, agencies have been required to submit proposed rules to the White House to give the administration a chance to weigh in. And Congress can block a rule it doesn’t like by passing a resolution of disapproval (subject to the president’s veto) or denying the agency the funds to carry it out. Lawmakers can also pressure agencies during the rule-making process by holding hearings and threatening legislation that would strip them of some power — both of which Republicans have done during the net neutrality proceedings.

What bothers congressional Republicans is that Wheeler — a Democrat whom Obama appointed in 2013 — seemed more responsive to the president’s ministrations than theirs. They’re worried about overly intrusive rules that dry up cable, phone and wireless companies’ investment in broadband; Obama was worried about overly permissive rules that didn’t stop Internet service providers from picking winners and losers online, drying up investment in the startups whose innovation is so important to consumers and the economy.

It’s worth noting that millions of Internet users, a slew of tech companies and dozens of venture capitalists were urging Wheeler to take a more stringently regulatory approach to net neutrality even before Obama weighed in. At least one of the other two Democrats on the commission didn’t think Wheeler’s initial approach was tough enough either, while the two Republican commissioners don’t want to adopt any rules at all. So the chairman’s initial proposal might not have passed anyway.

The challenge for the FCC is to hit the marks set by both sides: preserving opportunity and innovation for the next Google or Facebook without reducing ISPs’ investment. And it has to do so without going beyond its authority. That would be a much easier task if Congress had given the FCC clear power to protect net neutrality; instead, Wheeler had to fit an old law to a vital new purpose. Although important details remain to be seen, the new approach he has outlined — a stripped-down version of the strict utility-style regulation applied to local phone lines — seeks the right balance.

The commission is expected to vote on the proposal Feb. 26. If it passes, it is sure to be challenged in federal appeals court by one or more major ISPs. At that point, the only questions will be whether the commission exceeded its statutory authority and whether the evidence it collected over the last year provides sufficient support for the rules it adopted. If the commission prevails on those points, it won’t matter who changed Wheeler’s mind.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.