Editorial: Does California now have a utilities regulator it can trust?

- Share via

It took a deadly gas pipe explosion and the largest methane leak in U.S. history, but Sacramento has finally agreed to make major changes to the state Public Utilities Commission. The goal is to rebuild Californians’ confidence that the regulatory agency is working for them, and not for the energy companies it is supposed to oversee.

While not as far-reaching as some would like, the reforms worked out by Gov. Jerry Brown and legislators this week will go a long way toward addressing the persistent complaints that the PUC is too cozy with utility executives – and that consumers have paid the price in higher rates and compromised safety. Specifically, the deal puts more limits on private meetings between regulators and those who are trying to influence them, shifts the regulation of transportation companies to more appropriate agencies and makes PUC documents and meetings more accessible to the public.

The reform package represents an agreement between legislators, who have been trying to change the commission for years, and the governor who has, up to now, stood in the way.

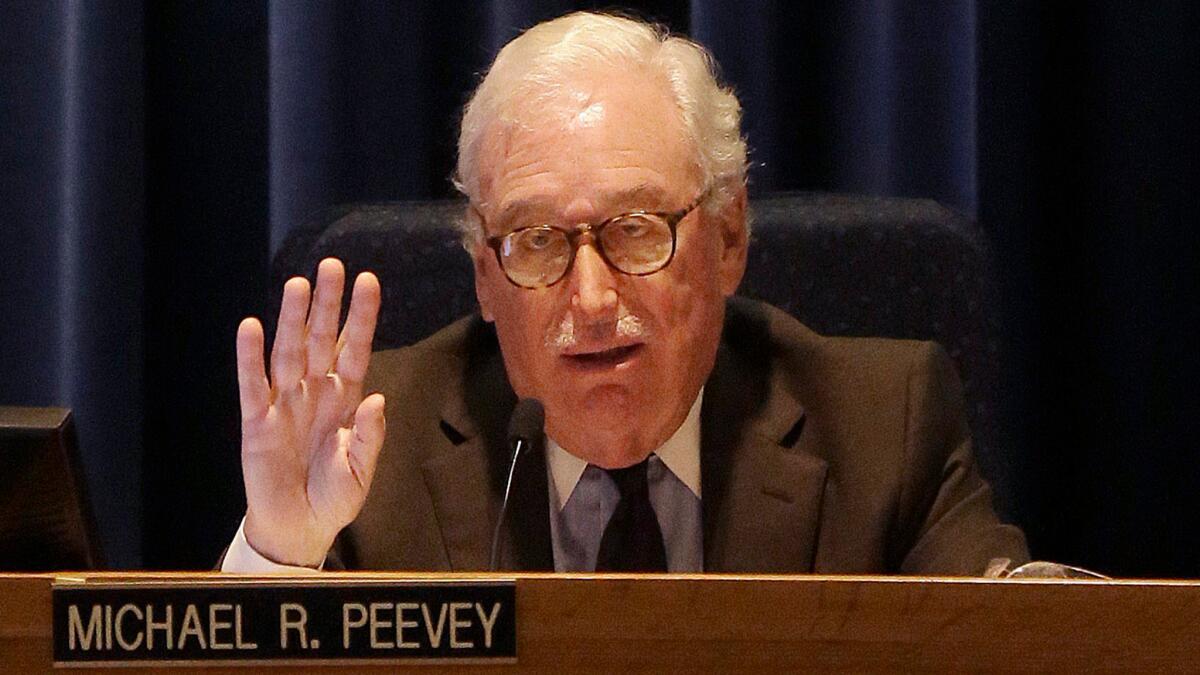

Legislators began trying to reform the agency in earnest after a gas line in San Bruno exploded and killed eight people in 2010. Later revelations that the commissioners – former Commission President Michael Peevey in particular – were overly tight with utilities executives cast doubt on decisions in the aftermath of the explosion and also on decisions about the 2013 closing of San Onofre nuclear power plant. Earlier this year, commissioners acknowledged that the $3.3 billion bill for the plant shutdown had been tainted by a meeting in Poland between Peevey and an executive for Southern California Edison, which owns 78% of San Onofre. They reopened the settlement agreement.

The PUC is unusual because it regulates a smorgasbord of industries. Formed about 100 years ago to regulate the monopoly that Southern Pacific Railroad Company had over the state’s rail and transportation, it was later extended to transportation companies (taxis, buses and, most recently, Uber and Lyft), as well as water, power and telecommunication providers.

What also makes the PUC unusual is the extent of ex parte communication employed in decision making. These are private meetings, calls, emails or texts between commissioners and those who are trying to influence the decisions they make. That won’t completely end with this deal, but it will be significantly curtailed; it will also be easier to bring criminal charges against those who violate the new restrictions. Incidentally, ex parte communication has also come under fire recently at the Coastal Commission, and legislation to ban that is pending at the moment.

Last year, Brown vetoed a package of PUC reforms, telling legislators he supported the intent but not some of the details. The current compromise may have been expedited by the leak at an underground natural gas storage facility in Aliso Canyon.

Adding fuel to the reform fire was a proposal by Assemblyman Mike Gatto (D-Glendale) to break up the commission and reassign its various responsibilities to other state agencies. As part of the current deal, Gatto will drop his bill and support the reform package. That’s a relief. Although the PUC has become a bit of a monster, it doesn’t merit the death sentence that Gatto was proposing.

One of Gatto’s gripes with the PUC – that it oversees too many incongruous industries and lacks the resources to do so properly – is a key part of the reform deal: Transportation-related responsibilities would be delegated to other state departments. For example, licensing and registration of ride-sharing vehicles would be moved to the Department of Motor Vehicles. That makes sense. Another notable change is the creation of a new executive-level position at the commission known as deputy director for safety. That person will have the authority (and, we hope, the clear responsibility) to red tag utility facilities and activities that are unsafe.

Nothing can ensure that California won’t experience another gas line explosion or gas leak, or that every rate will be unerringly fair to ratepayers. But these reforms will make Californians more likely to believe that PUC regulators have the public’s best interests in mind.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.