Editorial: Ending the Supreme Court stalemate

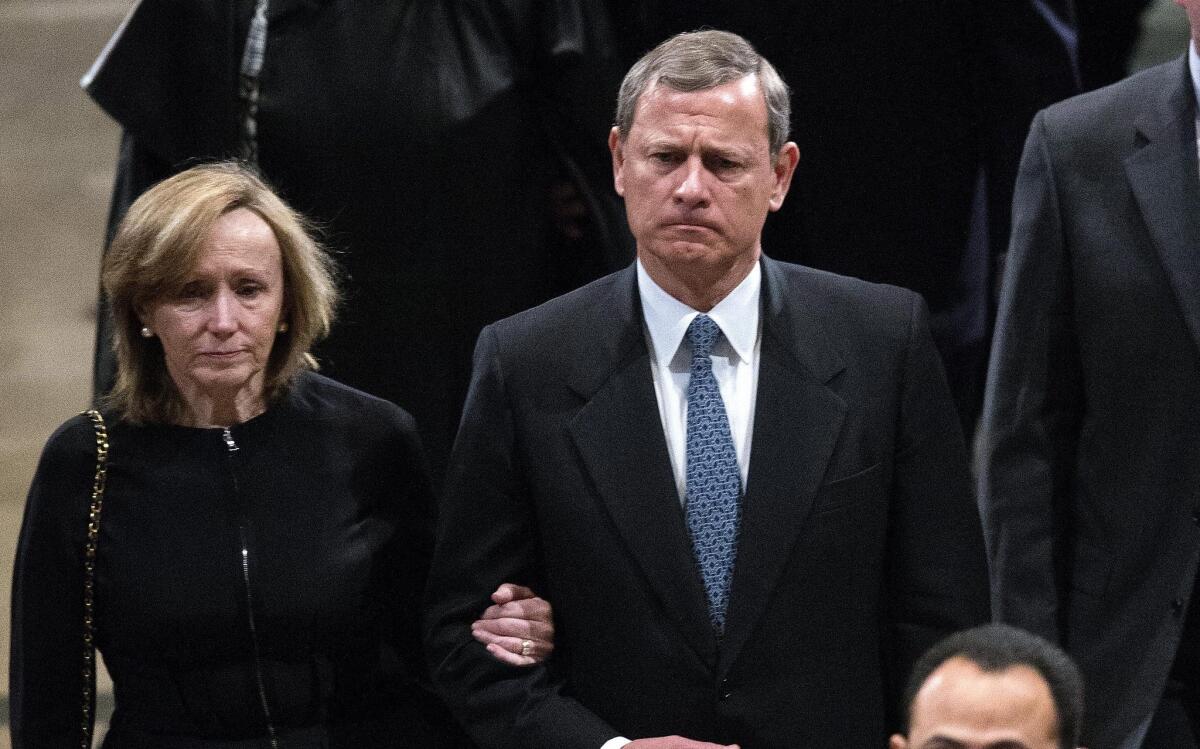

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts and his wife Jane Sullivan Roberts depart the funeral for the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia in Washington, D.C. on Feb. 20.

- Share via

On Wednesday, an eight-member Supreme Court heard a challenge to the requirement under Obamacare that employer health insurance plans cover birth control. The case was brought by nonprofit organizations with religious objections to contraception.

But questions from the bench suggested that the justices might be evenly split on whether the complicated arrangement worked out by the Obama administration to balance religious freedom and women’s health violates the nonprofits’ rights under existing law. If so, two outcomes are possible: The justices could hand down a 4-4 ruling that would not establish a binding precedent around the country, leaving the law open for interpretation. Or they could decide to have the case reargued next term in the hope that a successor to the late Justice Antonin Scalia will have been confirmed by the Senate.

Earlier this week the court divided 4-4 on another, less consequential, case, and further stalemates are likely if Senate Republicans continue with their ridiculous refusal to hold hearings on President Obama’s nomination of federal appeals court Judge Merrick Garland to fill the Scalia vacancy. But that’s not the only danger posed by the Republicans’ shameless stonewalling. An even greater risk, as Obama has warned, is “an endless cycle of more tit-for-tat [that would] make it increasingly impossible for any president, Democrat or Republican, to carry out their constitutional function.”

Obama is in good company in sounding such an alarm. Last month, in remarks delivered before Scalia’s death, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. lamented the politicization of the confirmation process.

Noting that Scalia and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg were confirmed by virtually unanimous votes in 1986 and 1993, respectively, Roberts said that in recent years the process had become much more partisan, with Democratic senators opposing Republican nominees and vice versa. “That suggests to me,” Roberts said, “that the process is being used for something other than ensuring the qualifications of the nominees.”

Of course, some would argue that the Senate should be guided not only by professional qualifications but by concerns about whether a nominee would move the court to the right or to the left. (That, not a desire to give voters a say in Scalia’s replacement, is the real reason for the Republicans’ resistance to Garland.) But the court and the country are ill served by this approach. It’s better for the Senate generally to focus on qualifications and accept that every president, by virtue of his election, has the right to try to shape the court. Presidents, meanwhile, should realize that if they put forward nominees who are too far outside the mainstream, the Senate will put up a fight.

Based on his comments last month, it would seem that the chief justice agrees. He would be doing his court and the Constitution a favor by explicitly calling on the Senate to do its job and give Garland a fair hearing.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.