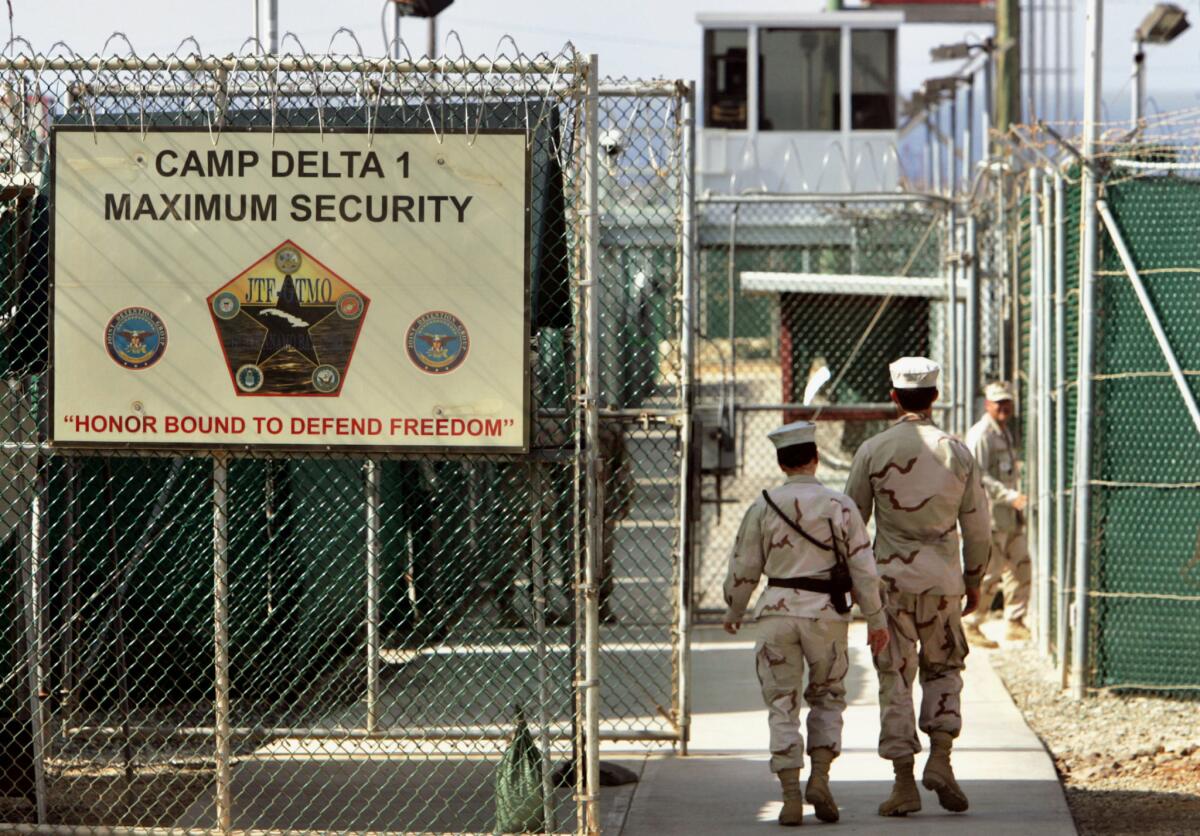

Don’t clone Guantanamo

- Share via

In recent months, President Obama has rededicated himself to his longtime goal of closing the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, and there are signs that Congress may assist him in making good on that promise. It will depend on whether the final 2014 National Defense Authorization Act follows language in the Senate version relaxing current restraints on transfers of the remaining detainees.

But even if additional prisoners are moved out of Guantanamo, it’s vital that the U.S. not solve its immediate problem by replicating the prison elsewhere. That concern is raised by reports that the Obama administration is negotiating with Yemen to construct a facility that would house as many as 30 of the 55 Yemenis the Pentagon has cleared for transfer. The Times’ David Cloud has reported that Yemeni officials have drawn up a plan for a facility outside the capital, Sana. But it hasn’t been established whether it would serve as a prison or as a sort of halfway house to help detainees reenter society after years of detention. Such efforts have had some success in Saudi Arabia, where they involve providing financial assistance and job placement to help detainees with reentry and religiously based exhortations against terrorism.

We have no strong objection if the U.S. decides to assist Yemen as it launches such a project to encourage repatriated detainees not to relapse or rejoin terrorist groups. But the U.S. shouldn’t build, much less operate, a Guantanamo-like prison in Yemen or collude in indefinite detention.

The problem with Guantanamo is not where it is but what it is: a prison in which most of the inmates have languished for years in legal limbo, theoretically able to challenge their confinement in U.S. courts but in fact deprived of meaningful due process. Many have been driven to despair; quite a few have attempted or committed suicide. The current population includes not only about 80 who have been cleared for release and others awaiting trial by military commission, but also some 40 prisoners the U.S. has decided are too dangerous to release but who can’t be put on trial because of compromised or inadmissible evidence.

In a speech in May at the National Defense University, President Obama reiterated his commitment to shut Guantanamo, arguing that “there is no justification beyond politics for Congress to prevent us from closing a facility that should never have been opened.” He even floated the possibility that the status of detainees deemed too dangerous to be put on trial might be resolved consistent with principles of American justice. (Sadly, action on that commitment hasn’t been forthcoming.)

Obama rightly observed that Guantanamo “has become a symbol around the world for an America that flouts the rule of law.” But precisely the same message would be sent if inmates were released from Guantanamo, only to be held indefinitely under U.S. control in other countries. Guantanamo needs to be closed, not exported.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.