Petraeus and the blackmail myth

- Share via

In 1954, psychologist Benjamin Karpman wrote a prescient book about “sexual offenders” in the United States. Karpman focused especially on homosexuals who were drummed out of government jobs on the grounds that their sexual orientation made them security risks. If you were gay, the argument went, you were susceptible to blackmail by communist spies.

But the real problem lay in the taboo on homosexuality, which paved the way for exactly the kind of extortion that the government feared. “The easiest way to prevent the blackmailing of homosexuals is to recognize homosexuality as a fact and to remove the unreasonable laws which discriminate against it,” Karpman argued.

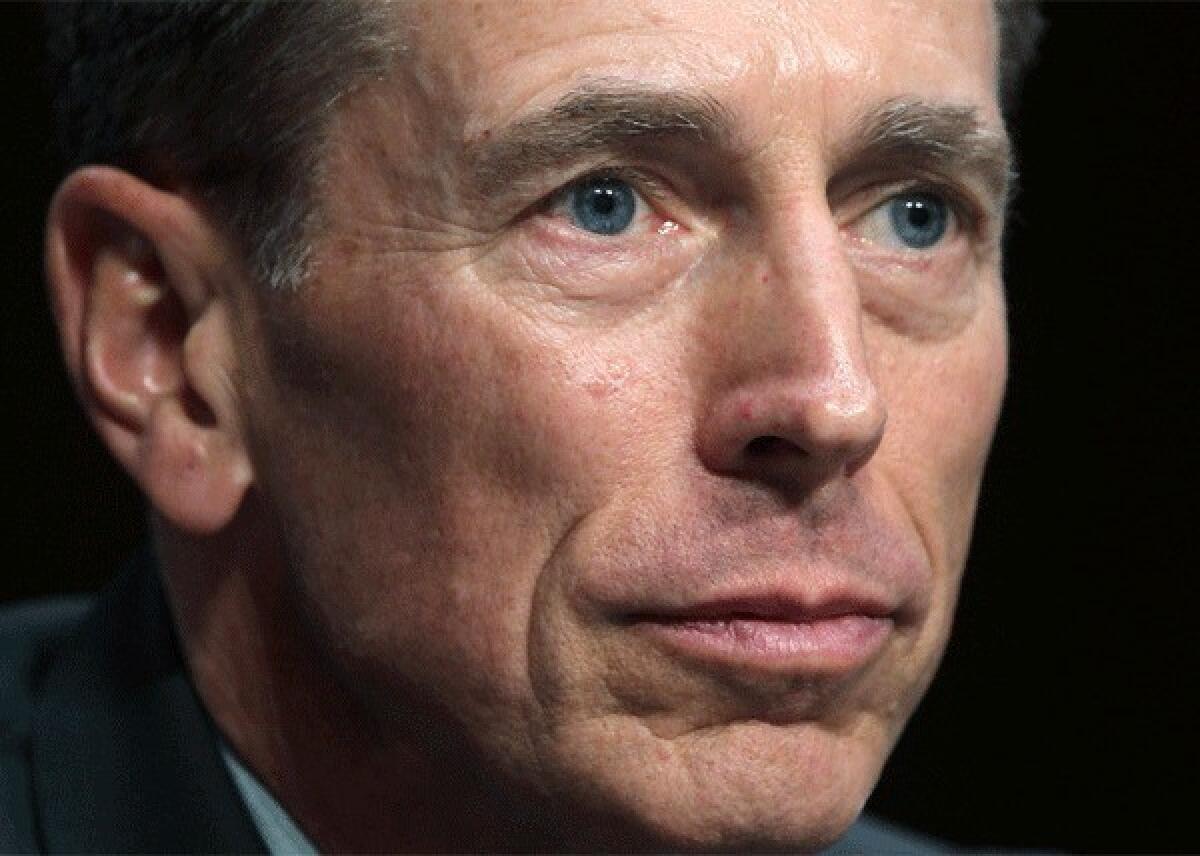

I’ve thought about this history during the ongoing scandal over former CIA Director David H. Petraeus, who resigned last week after admitting to an extramarital affair. If Petraeus had been an elected official — think President Clinton, circa 1998 — he might have weathered the storm. But adultery by such a high-ranking figure in the intelligence community was unpardonable, the conventional wisdom says, because it opened Petraeus to — you guessed it — blackmail.

But if that’s true, it’s as much the nation’s fault as Petraeus’. Call it the self-fulfilling prophecy of blackmail: The more we police purely private behavior, the greater the risk of public exposure.

Consider the Mann Act of 1910, passed to fight the “white slave trade” and prostitution. The measure made it a federal offense for a man to transport a woman across state lines for a sexual purpose, unless she was his wife.

It also made a great new line of business for blackmailers like “Dapper Don” Collins, whose gang extorted more than $200,000 from dozens of victims. Collins used young women to lure older, wealthy men into taking them from, say, New York City to Atlantic City, where they would be confronted by gang members who posed as policemen and demanded a bribe.

That’s why critics took to calling the Mann Act “the Blackmail Act”: In the guise of fighting prostitution, it promoted a vice at least as bad as the one it sought to interdict.

Ditto for government attacks on homosexuals, who were barred from federal civil service jobs in 1953. For the rest of that decade, about 60 employees were fired each month on suspicion of being gay. According to Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who spearheaded the Cold War hunt for subversives, “the pervert” — that is, the homosexual — “is an easy prey for blackmailers.”

Actually, as historian Angus McLaren has noted, federal investigators failed to uncover a single instance of a foreign agent blackmailing an American for being gay. But homosexuals did face blackmailing threats from domestic crooks, just as adulterers did during the Mann Act scare.

In 1966, for example, New York police arrested nine people for enticing men into gay trysts and extorting millions of dollars from them. Victims included teachers, professors, actors and businessmen as well as a congressman, an admiral and a general.

Even worse, some police officers engaged in blackmail instead of guarding against it. Interviewing gays in St. Louis in the 1960s, sociologist Laud Humphreys found that almost all of them had paid off the police at some point. Indeed, Humphreys wrote, “most blackmailing is done by law enforcement personnel.”

Would Petraeus have faced similar threats from blackmailers inside the government? I doubt it. According to news reports, FBI agents quietly investigated Petraeus’ affair for some time before deciding that there was no evidence of criminal activity on his part.

Compare that to the FBI’s tawdry record in the past, and you’ll see how far it has come. In addition to harassing suspected gays, agents recorded Martin Luther King Jr.’s adulterous liaisons. The agency’s files show they even sent a tape of King having sex with a mistress to his office in Atlanta, accompanied by a note urging him to commit suicide.

Fortunately, today’s FBI is much more cautious and judicious when it comes to sexual matters. Indeed, some members of Congress are complaining that the agency didn’t let them know about the Petraeus investigation early enough.

But they didn’t have to know, and neither did we. To be fair, it’s still not clear whether Petraeus shared any government secrets with Paula Broadwell, his biographer and mistress. Nor do we know what she included in the allegedly threatening emails she sent to Tampa, Fla., socialite Jill Kelley, which started the investigation. Based on what’s been reported, though, it’s hard to see how Petraeus’ behavior put national security at risk, any more than gays did during the Cold War. Some enterprising thug might have used Petraeus’ behavior to blackmail him, I suppose, but that wouldn’t work unless the rest of us thought adultery disqualified him for office. And I still don’t see why it should.

Writing in 1970, Humphreys noted that homosexuals were “discriminated against for being prone to blackmail.” So was Petraeus, a dedicated public servant done in for his poor private decisions. We’re all poorer without him.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches history and education at New York University. He is writing a book about sex education since 1900.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.