Our immodest proposal

- Share via

The Times ran an Op-Ed article on Dec. 28 with the headline “Crayons, pencil, gun: What’s missing from the typical kindergartner’s backpack? A pistol.” The writer, Daniel Akst, was responding to what he considered an absurd suggestion by the National Rifle Assn. to install armed guards in schools. But rather than write about the NRA proposal directly, Akst wrote about the issue satirically, suggesting that we go a step further and arm children.

“We make vaccinations mandatory for most children; why not firearm training?” he asked. “To be admitted to kindergarten, a child would have to demonstrate basic proficiency with a pistol. After that, no child should be able to advance a grade without meeting certain weapons milestones.”

The article was intended to be so absurd that readers would see it as humor rather than as a serious proposal, and many readers wrote to say they enjoyed the joke.

Some, however, assumed Akst meant what he wrote.

“Seriously, does Akst really believe that a group of elementary students with pistols could possibly protect themselves against a predator with an AK 47?” one reader, a veteran educator, wrote. “We already have too much violence, and adding to it by arming our students is ludicrous.”

Another reader asked, “What was Daniel Akst smoking when he wrote this horrible article?”

Should we have made it clearer that Akst was writing tongue-in-cheek if clearly intelligent readers didn’t get the joke?

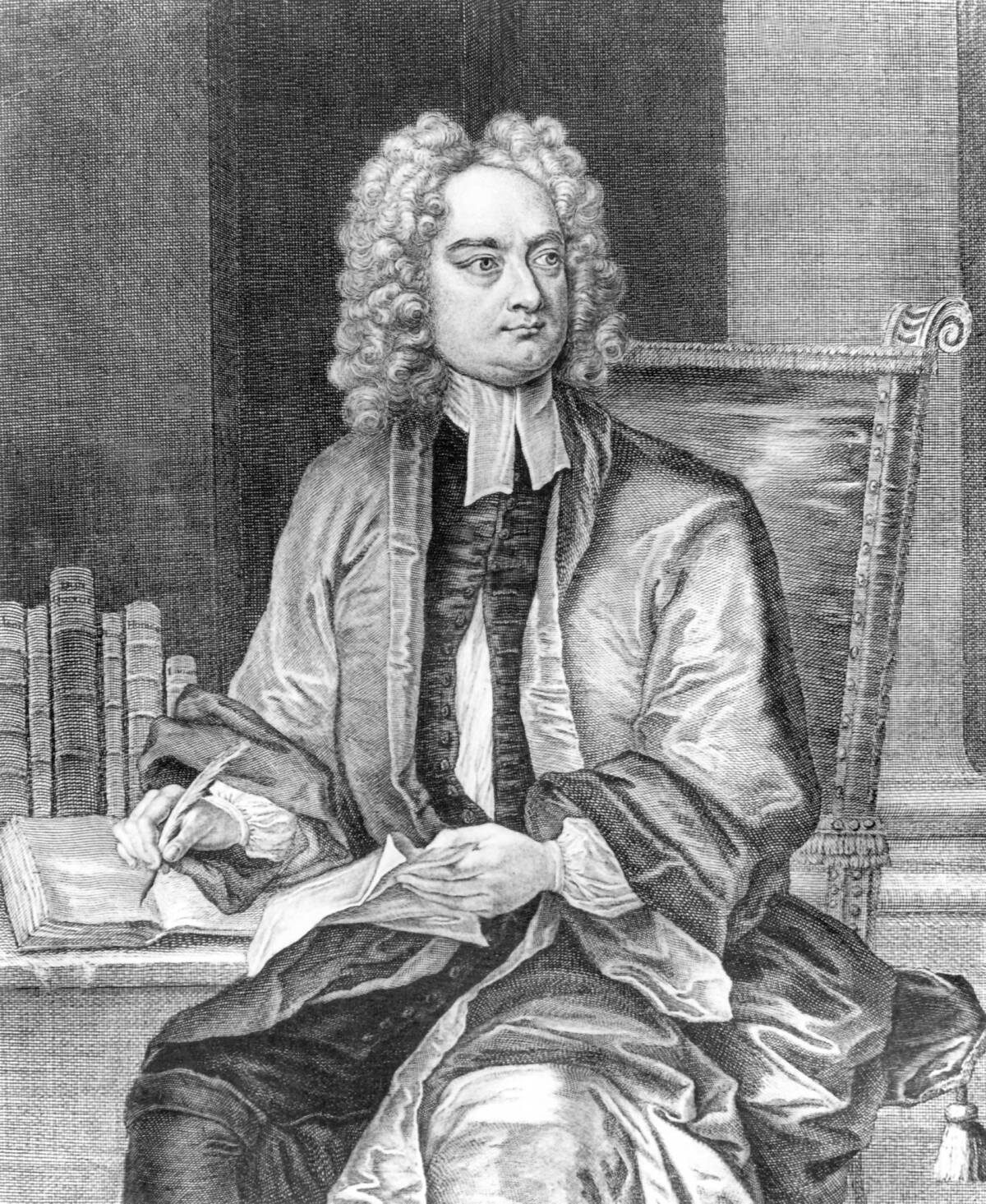

It’s not a new dilemma. Perhaps the most famous piece of satire ever written, Jonathan Swift’s 1729 essay “A Modest Proposal,” was intended to lampoon the indifference of the affluent toward extreme poverty in Ireland. In the treatise, he proposed that the babies of poor Irish families should be purchased and eaten by the wealthy, which would make for fewer poor children, while at the same time providing a ladder out of poverty for families.

Swift’s argument was so arch he assumed it would be understood as satire. “A young healthy child,” he wrote, “is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.” Not only would the proposal relieve the streets of child beggars “importuning every passenger for an alms,” he suggested; it would also be “a great inducement to marriage,” since parents would be lured into matrimony by the financial inducement of producing and selling babies.

Though many of Swift’s readers got the joke, his “modest proposal” was attacked by others as heartless and cruel, and Swift himself was called a cannibal and worse. Even today, when the essay is assigned to high school classes, some students are outraged rather than amused.

By their very nature, satiric pieces run the risk of being taken seriously. That risk could be eliminated, of course, by making the joke clear in an introduction. But underlining humor in that way can also undercut it.

We do like to run the occasional piece of satire in Op-Ed, and we intend to continue to publish it. But we will also continue to look for ways — through headlines, say, or visual presentation — to better tip the reader to the joke. If we fail occasionally, as we almost certainly will, we apologize.

Sue Horton is The Times’ Op-Ed editor.

ALSO:

Letters: Losers in the ‘fiscal cliff’ law

Letters: State legal fund does its job

Letters: The filibuster and the framers

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.