War on terror: Life, death and drones

- Share via

On Friday, a federal judge in Washington will hear a challenge to the Obama administration’s approach to targeted killings. I find myself frustrated by how little progress we’ve made.

In 2004, I represented Guantanamo Bay detainees in the Supreme Court in Rasul vs. Bush, challenging President George W. Bush’s claim that he could hold noncitizens at Guantanamo without judicial review based on the administration’s unilateral claim that the detainees were enemies of the United States. I argued that the president’s position presented a profound threat to the role of the courts in safeguarding the rule of law, and that the prisoners were entitled to due process, including judicial examination of the government’s reasons for holding them. The Supreme Court agreed, reaffirming that an asserted “state of war is not a blank check” for the executive branch when civil liberties are at stake.

When campaigning for office, then-Sen. Barack Obama agreed with the court’s decision and criticized Bush’s abandonment of basic checks and balances in the so-called war on terror. Yet today, President Obama has taken his predecessor’s assertion of executive fiat even further. His administration says it has the power not just to detain suspected terrorists but also to kill them without any judicial oversight or accountability.

POLL: How do you feel about the FBI using drones?

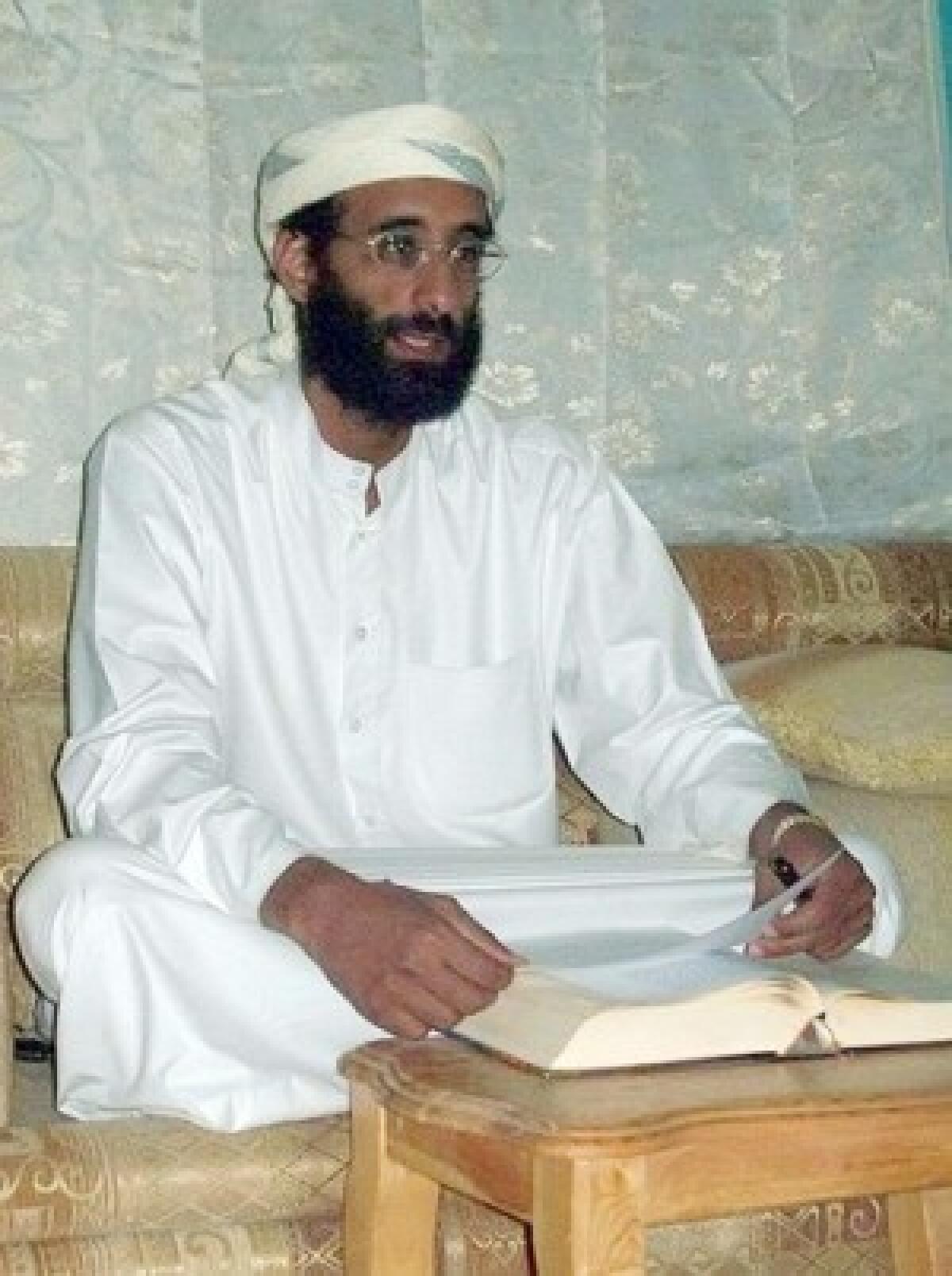

That dramatic claim of authority is at issue in a lawsuit brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights and the American Civil Liberties Union, which challenges the 2011 extrajudicial killing by drones of three American citizens, including an alleged (but never criminally charged) terrorism suspect, Anwar Awlaki, his companion Samir Khan — and, two weeks later and hundreds of miles away, 16-year-old Abdulrahman Awlaki, Anwar’s son, whom no one had accused of wrongdoing. The lawsuit charges that the killings violated the Constitution, including its most elementary protection against the deprivation of life without due process of law.

Seeking to dismiss the lawsuit, the Justice Department has maintained that such killings are immune from judicial review. The administration argues that due process does not require judicial process and that we should trust the executive’s judgment when it takes the lives of its own citizens abroad. That position — that the government should be able to use lethal force against individuals it deems to be a threat based on a secret executive process using standards and evidence that are never tested by a court — is disturbingly familiar. Indeed, it is just as much an affront to the rule of law as it was in 2004 when it was defended by the Bush administration.

Our constitutional system of separation of powers demands a role for courts when individual liberties are at issue. This premise is not only made plain by the 5th Amendment’s guarantee of due process, it has also been repeatedly vindicated by historical experience.

The Bush administration defended the secrecy surrounding Guantanamo detainees — and its contention that due process was unnecessary in their detention — by saying its actions were justified by danger the men presented. The administration insisted that the courts should simply accept its determination that all of them were hardened terrorists or the “worst of the worst” — a once-popular claim that was proved manifestly false after the Rasul decision permitted legal access to the men. Likewise, the Bush administration’s solicitor general tried to reassure a skeptical Supreme Court to trust its unilateral executive authority by proclaiming that the “U.S. does not torture” — a claim dramatically belied by pictures from Abu Ghraib released just days later.

The Obama administration is following a disturbingly similar course, attempting to reassure the public that it is making life-and-death decisions with careful deliberation and concern. But hidden processes that lack sufficient transparency and meaningful checks inevitably produce errors. The killing of 16-year-old Abdulrahman Awlaki, whom the government has said was not “specifically targeted,” is but one example that makes this all too clear.

Equally important, we sacrifice a core requirement of our constitutional republic when decisions about such grave deprivations of life and liberty rely solely on the judgment of one branch of government, no matter how well-meaning it may be. As Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson warned in a landmark case decades ago, claims to unreviewable executive power predicated on an amorphous and unlimited state of war are particularly dangerous because “such power either has no beginning or no end.”

In Washington on Friday, lawyers for two families who have lost relatives to U.S. drone strikes will ask a federal court to continue the judiciary’s long-standing and vital role in our constitutional system. In doing so, the court can remind the executive branch that a fair and open legal process is most important when it comes to matters of life and death.

John J. Gibbons, a director of a New Jersey law firm, is the former chief judge of the U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.