Gettysburg Address plus 150: Are we letting Lincoln down?

- Share via

It was a dim, damp November Thursday in Gettysburg, Pa., 150 years ago, the ground muddied from rain, the weather much different from the July days of a few months before.

The people and the place too were stiller — no gunfire, no thunder of artillery, no shrill of trumpets, no rebel yells, no screams from men and horses torn to pieces.

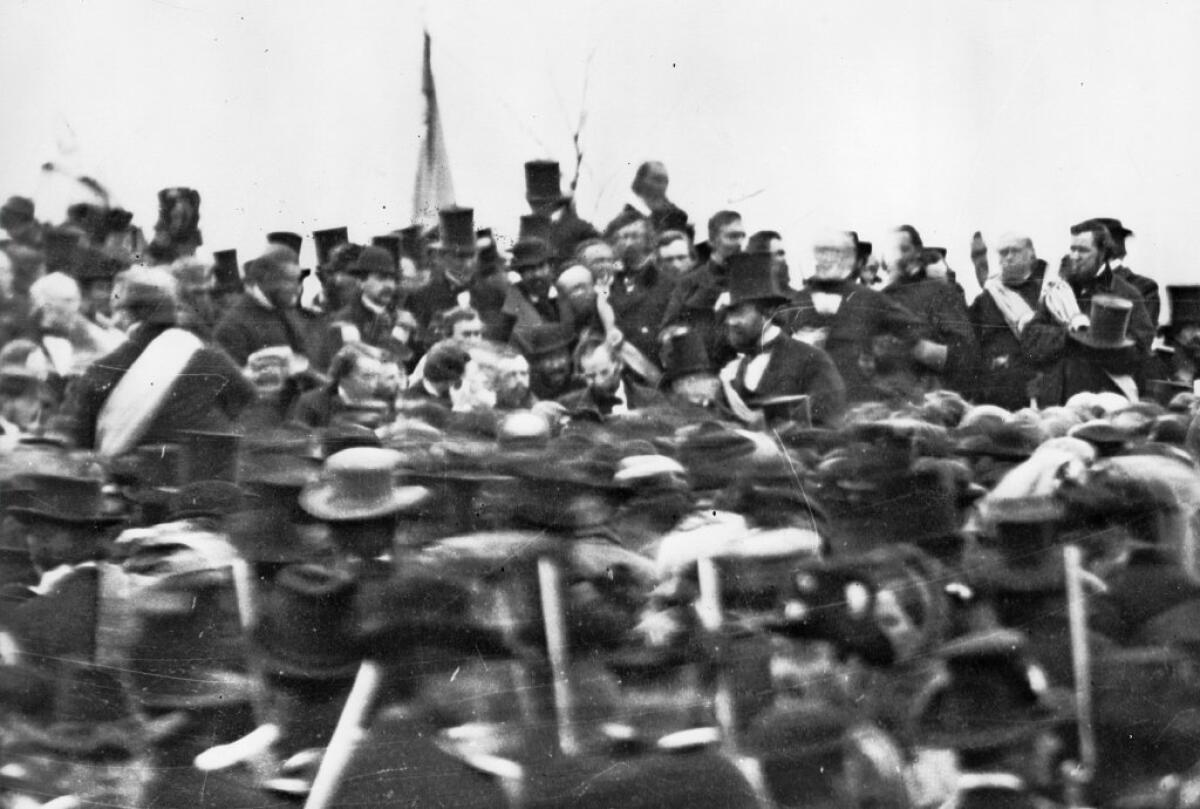

Some 15,000 people showed up at Gettysburg on Nov. 19, 1863, to hear other sounds — the speeches dedicating the new federal cemetery where many thousands had fought four months earlier, and where some 7,000 men had been killed.

Edward Everett was the star-turn speaker that day, and he did not let down his audience, holding forth for about two hours. It was an age of orotundity and rodomontade, words perfect for the era, when speeches were entertainment and were expected to last for as long as a feature film does now.

President Abraham Lincoln’s fabled back-of-the-envelope remarks — 10 perfect sentences, about 270 matchless words — were over before the photographer got a shot, before most in the audience had settled in for what they expected to be another good long disquisition. Here is what they got instead:

“Fourscore and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

“But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth.”

Lincoln got only one thing wrong that day, when he said “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” The world remembers. Winston Churchill said the speech was “the ultimate expression of the majesty of Shakespeare’s language” — language that Lincoln read often and loved.

As prose, it is so enduringly beautiful that a copy was left at every place at every table at last month’s International Women’s Media Foundation dinner in Beverly Hills. As politics, it is a sublime iteration of what this country is supposed to be.

Before the Civil War, I read, the phrase people used was “The United States of America are.” After the war, the plural became the singular: “The United States of America is.”

Look at us now, 150 years later, sundered by natural and manufactured divisions, and paralyzed by them. Do we remember these admonitions and cautions, except selectively and by lip-service? Shame on us that we don’t. Every member of Congress, every member of every legislative body, every American should stop Tuesday and sit together and read these words or hear them read.

One hundred and fifty years is not so very long ago. I once found myself only two people away from Lincoln and his speech. One day in the 1990s, I had read the Gettysburg Address on the air on KCET-TV, and an elderly man called me up afterward to tell me his story. When he was a boy of 8 or 9, a guest at his family’s dinner table was an elderly man who had been in Gettysburg and had heard Lincoln give that speech — with some of the same inflections I had given it.

My caller had never forgotten that, and now neither have I. Time is so thin a plane, and history a glass so easily broken.

It’s natural to regard the battle of Gettysburg as the fulcrum of the war, but the Gettysburg Address was the fulcrum of the peace. Today it feels like we are dangerously far from the vision of Lincoln’s speech. Our leaders have been playing the finely tooled keyboard of democratic governance with gleeful gracelessness and truculence, and no wonder the notes that come out of it are so jarring. Instead of finishing the work Lincoln laid out for us, we seem bent on undoing it.

ALSO:

Would you break the law for your family?

McManus: JFK: a presidency on a pedestal

Esperanza Spalding: Music to shine a light on Guantanamo Bay

Follow Patt Morrison on Twitter @pattmlatimes

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.