Does the death penalty deter would-be killers?

- Share via

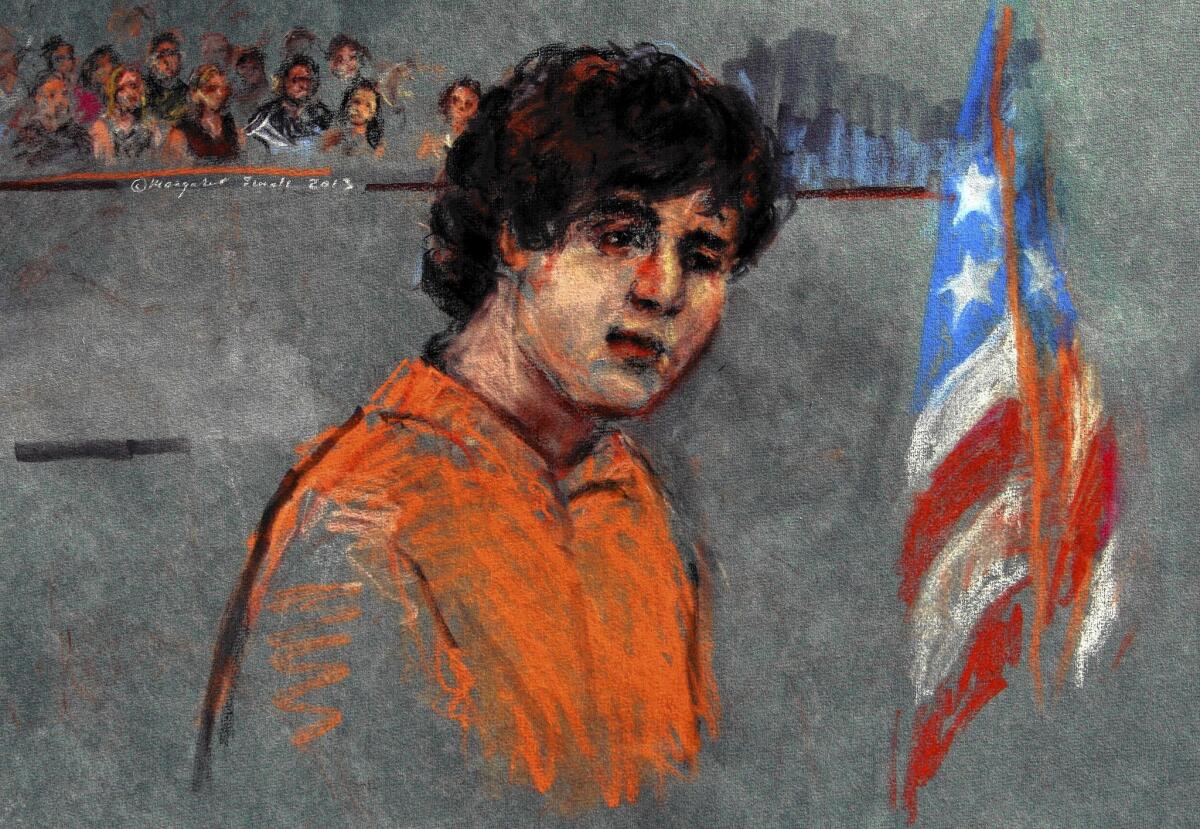

The Times’ editorial Sunday opposing the death penalty for accused Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev prompted Robert S. Henry, a retired capital case coordinator with the California attorney general’s office, to write a letter defending capital punishment:

“The Times says that life imprisonment without parole is sufficient for Tsarnaev because it ‘punishes the criminal while protecting society from future acts of violence.’ This limits the purpose of capital punishment.

“The death penalty is also there to deter others from committing murder. The prospect of having lifetime room and board for those contemplating murder is not much of a deterrent. Moreover, providing those benefits hardly seems to balance the moral scale when the victims have lost their lives.”

Editorial writer Scott Martelle responds:

On the surface, the deterrence argument seems logical and defensible. Who would commit a crime knowing that to get caught means your own death?

The reality: Studies have not shown a connection between awareness of the death penalty and a decision to act. In fact, given the simultaneous existence of the death penalty in the United States and our high murder rates (compared with other developed nations), it’s hard to see a correlation. The Death Penalty Information Center reports a general decline in executions from 98 in 1999 to 39 in 2013, a time frame over which the national murder rate dropped roughly from 5.6 per 100,000 to 4.7. Yet no one argues that reducing the execution rate reduces the murder rate.

When it comes to the death penalty, deterrence is a nonissue. People who are enraged, under the influence of drugs, suffering from mental illness or who, in some cases, lack the mental capacity to understand their actions usually do not stop to think of the consequences. And while some who premeditate murder might, on reflection, abandon the plan (an immeasurable occurrence), enough alleged murderers are accused of premeditation to suggest that the death penalty is considered and then discarded.

The more fundamental issue here is a moral one: Should we grant our government the power to execute people? No, we shouldn’t; a premeditated killing by the state is still a premeditated killing. And it’s striking that many of the same people who don’t think the government can get anything right believe it can get the death penalty right. As we’ve seen from the Innocence Project and other activist groups, there is sufficient error and manipulation in the judicial system to raise serious questions about whether all of the people executed in our names were, in fact, guilty. The dead have no right of appeal.

That isn’t the issue in the Tsarnaev case. There are no arguments (yet) over proper identification, coerced witnesses or access to capable legal representation. If Tsarnaev is found guilty, he should face the harshest morally defensible punishment we can exact: life without a chance of parole.

More broadly, as a nation we should end this embrace of barbaric blood-thirst for revenge and join the two-thirds of the world’s nations that do not use capital punishment. Because it is the moral thing to do.

ALSO:

Letters: Climate change and Keystone XL

Letters: Senioty-based teacher layoffs must go

Letters: Immigration reform not a priority issue

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.