Op-Ed: Philanthropic naming rights, and naming wrongs

- Share via

Poor David Geffen. By giving $100 million to New York’s Lincoln Center to rename Avery Fisher Hall after himself, he’s become the new focus of a philanthropic debate that has gone on for decades.

There are three schools of thought when it comes to big-ticket charity. The first is the Purist School, which embraces the Biblical admonition to let not your right hand know what your left hand is doing in alms-giving, as well as the teachings of 12th century philosopher Moses Maimonides. In other words, the most noble form of giving is that which is done anonymously. Advocates of this position, as you might imagine, are horrified by Geffen’s apparent insistence on slapping his name on every theater, museum, hospital and building he touches.

But they miss the point that it was Lincoln Center’s leaders who were shopping around the naming rights for the concert hall. In fact, they negotiated a $15-million payoff for Avery Fisher’s heirs last year in order to start the bidding. Geffen was the highest bidder, that’s all.

The anonymous gift is pretty much extinct in 21st century America anyway. In fact it never got well-established here. Just ask John Harvard, Eli Yale, Leland Stanford and James Smithson.

The second school is the Honor/Obligation Group, which dominated in the 20th century. Money was always involved, but the naming of buildings was cloaked as an honor for services rendered to the institution or the field. In an old fundraising joke, a rich executive’s assistant is holding her hand over the phone mouthpiece, saying, “It’s your alma mater, sir. They want to give you an honorary degree.” “Tell them I’m sorry,” the boss replies, “but I’ve gotten all the honor I can afford this year.”

Avery Fisher fit perfectly into this Honor/Obligation philanthropic mold. He was an accomplished amateur violinist and revolutionized sound reproduction through his Fisher radios and phonographs. He served on the board of the New York Philharmonic for years and in 1973 gave Lincoln Center $10 million as an endowment for what was then Philharmonic Hall. They renamed the 11-year-old building for him and a few years later used much of the money for an acoustic renovation. Fisher may have agreed to share his name with the concert hall, but he didn’t buy naming rights. That Lincoln Center is sandblasting Fisher’s name off the building only 20 years after his death — and paying off his children to do so — may seem crass all around, but it is not illegal.

The third and currently dominant model is Transactional Philanthropy, or Charity by Lawyers. Here the charitable impulse is codified. You put your money down, sign here and your name goes on the building. Most big-ticket naming is formulaic. Want to endow a university professorship? That’ll be $5 million, $6 million at a top-tier school. Want your name on a building? That’ll be 25% of the construction cost, plus 5% more for long-term maintenance. Some fundraising insiders think Geffen got a bargain paying only $100 million for a $500-million project.

Transactional philanthropy contracts often spell out the terms of a gift with great specificity. There is certainly a minimum length of the naming obligation; perpetuity is usually off the table. There are default provisions as well, such as: What if the donor goes bankrupt or to the clink before the gift is completed? And, of course, details on branding. I don’t know who came up with calling the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts “the Wallis,” but I doubt it sprang up spontaneously from its Beverly Hills patrons.

Branding, which is at the heart of philanthropic naming, can be tricky. Will the full name David Geffen Hall stick? New Yorkers notoriously shorten even nicknames (A-Rod, MOMA, the Met). It could become the Geff.

But if our billionaire becomes displeased with his Lincoln Center agreement, there is another juicy opportunity awaiting him in his adopted home town. “Mr. Geffen, the Los Angeles Music Center is on the line. They want to give you an honorary baton.”

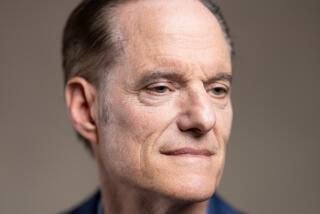

Jack Shakely is president emeritus of the California Community Foundation.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.