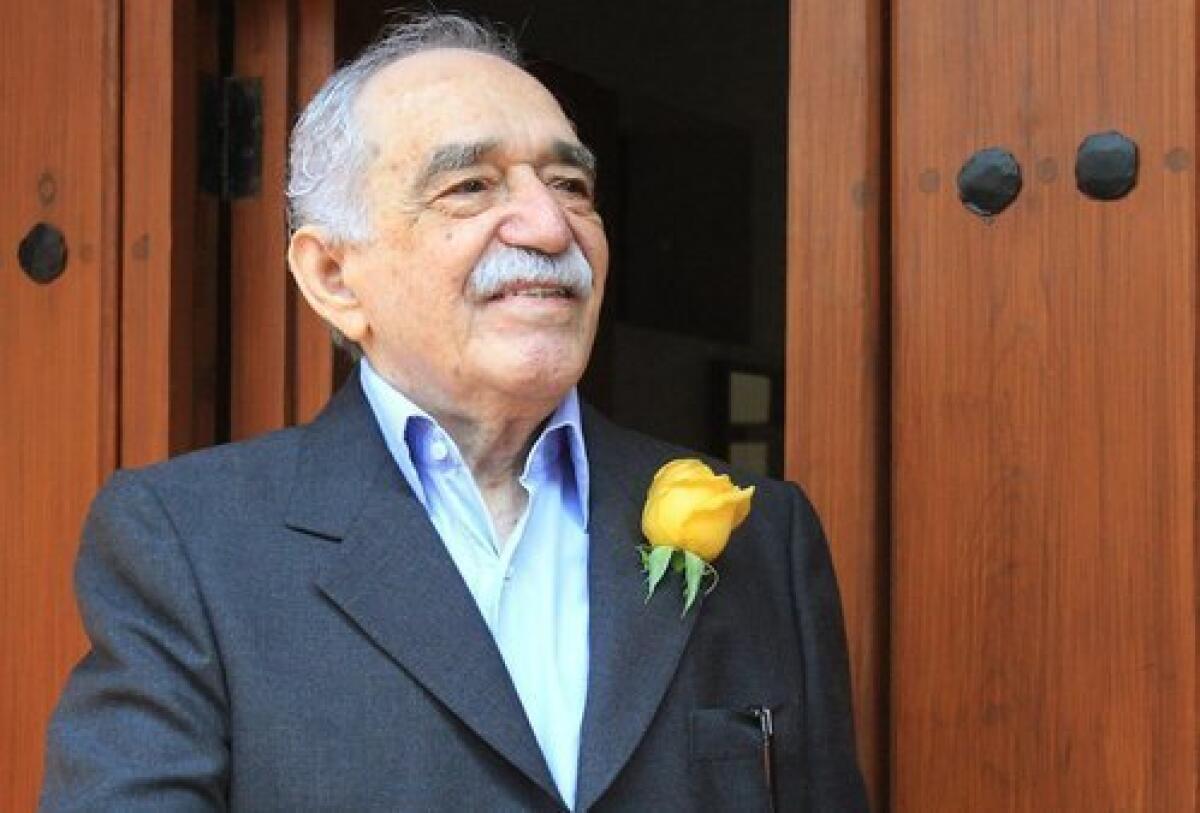

Op-Ed: Gabriel García Márquez takes his place in the pantheon

- Share via

Reporting from Mexico City — The first time I met Gabriel García Márquez, then an unknown writer in Mexico, was on July 6, 1962, in the office of the producer of Luis Buñuel’s movie “Viridiana.” I remember the date well because after noticing the headline, Gabo asked to borrow the evening paper I had just bought, exclaiming “Dammit, today my master died,” referring to William Faulkner.

Faulkner famously detested intrusions in his private life, and the funeral in his native Oxford, Miss., was sparsely attended by several dozen family members, his publishers and a few writers. In his chronicle of the event in Life magazine, William Styron describes the “monumental heat” as the procession drove past stores closed for the event and townspeople lining the streets, although, according to a local resident, “None of them ever read a word of him.” The coffin was buried “on a gentle slope between two oak trees.”

My wife, Betty, and I would occasionally run into Gabo at the Café Tirol, a writers’ and artists’ hangout in the Zona Rosa here. One afternoon in 1963, he gave us a ride home. When we got out of the car, he asked if I had read “Big Mama’s Funeral.” I had never seen the book anywhere. Throwing open the trunk to reveal stacks of copies, he said, “Take as many as you want; at least someone intelligent will read it.”

One day in 1964, Ramón Xirau, editor of the literary magazine Diálogos, where I was assistant editor, invited Gabo and me to a fancy restaurant for lunch. For an hour Gabo and I stood waiting by the cash register, until Gabo suggested that I invite him to lunch myself. I didn’t have a cent, as Xirau was supposed to pay me that day. Gabo didn’t have any cash either. Finally we called Xirau’s house, to be told by the maid that he was lunching with his in-laws. Gabo and I went to our homes to eat alone, for our wives had made other plans.

Everything changed for Gabo in 1967 with the publication of “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” greeted with rabid enthusiasm by readers and reviewers. In New York, I saw a Puerto Rican talking to a lion in the Central Park Zoo, shouting “Hey, Charlie, hey Charlie” as he pounded on a copy of “Cien Años de Soledad.” Aracataca, Gabo’s birthplace in Colombia, had metamorphosed into Macondo, midwifed by Rabelais and Kafka, Faulkner and Juan Rulfo, whose “Pedro Páramo” and “The Burning Plain” had been pressed on him by the Colombian novelist Álvaro Mutis with the admonition to read them and learn how to write.

During the first Ibero-American Summit, held in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 1991, Gabo and I presented a proposal for a continental environmental alliance to the assembled heads of state, including King Juan Carlos of Spain, Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and Secretary-General of the United Nations Javier Pérez de Cuéllar. Protection of forests and a pact to save the Amazon were among our priorities, along with migratory species such as sea turtles and birds.

On Aug. 24, 2005, we met in the Church of Santo Domingo at the funeral service for Natasha Fuentes Lemus, Carlos Fuentes’ younger daughter, who had been found dead two days earlier. Gabo turned to me and said, “Damn, I’m not going to write anymore.” His wife, Mercedes Barcha, asked, “Why do you tell Homero that?” to which he replied, “If I don’t tell Homero, whom should I tell?” And indeed, “Memories of My Melancholy Whores,” published in 2004, was his last book.

At 3:18 p.m. today, April 21, the funeral procession with Gabo’s ashes departed from his home of the last 30 years on Fuego Street, escorted by a phalanx of traffic police on motorcycles for the 12-mile drive to the ornate Palace of Fine Arts in downtown Mexico City, where long lines of fans patiently awaited their chance to stand guard beside the urn for a moment, after passing through strict security procedures. Prolonged applause greeted the urn when it was placed on a pedestal shortly after 4 p.m.

Live coverage on national TV had begun in midafternoon. Inside the palace a string quartet played excerpts from Gabo’s favorites: Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, Dvorák and Mendelssohn, while outside a trio playing the popular Colombian folk music known as vallenato alternated with readings from Gabo’s books. A storm broke as luminaries from the world of literature and politics gathered in the palace waiting for Enrique Peña Nieto, president of Mexico, and Juan Manuel Santos, president of Colombia, to make their entrances and give their speeches. Absent from the cultural diplomacy and presidential homage was Fidel Castro, Gabo’s friend since the 1960s.

As the special guests exited the Palace of Fine Arts, a blizzard of yellow paper butterflies was blown over the crowd, still looking forward to a few seconds of Gabo’s magical aura.

Word has it that as a son of both countries, Gabo’s ashes will be shared by Mexico and Colombia, unlike those of his great friend Carlos Fuentes, who chose to be buried in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris, where the remains of Natasha and his son, Carlos, already lay, or those of his fellow Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz, thought to still be in the possession of his widow.

Another Latin American Nobel winner, poet Pablo Neruda, died in Santiago, Chile, on Sept. 23, 1973, 12 days after the CIA-backed military coup against Salvador Allende’s government. All public meetings were forbidden, but when his widow, Matilde Urrutia, set out from their house, which had been vandalized during the coup, with his coffin and a military escort, she was joined along the way by some 2,000 people. Upon arriving at the cemetery, they began to sing the socialist anthem “The Internationale.” Neruda’s death had prompted the first open protest against Augusto Pinochet.

When Victor Hugo died in 1885, he was hailed as a hero of the Third Republic and his body lay in state under the Arc de Triomphe and military regiments and bands escorted the funeral carriage down the Champs-Élysées, past chestnut trees in blossom, and across the Pont de la Concorde to his final resting place in the Panthéon. Two million people were reported to have followed its progress.

Surely that many and more followed today’s homage to Gabo on television. One thing is for certain, however: Magic realism has died with its most wildly imaginative practitioner.

Homero Aridjis is a poet, novelist, environmentalist and former Mexican ambassador to UNESCO, and the author of “A Time of Angels.” This essay was translated by Betty Ferber from the Spanish.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.