4 myths that make L.A. County’s homeless problem worse

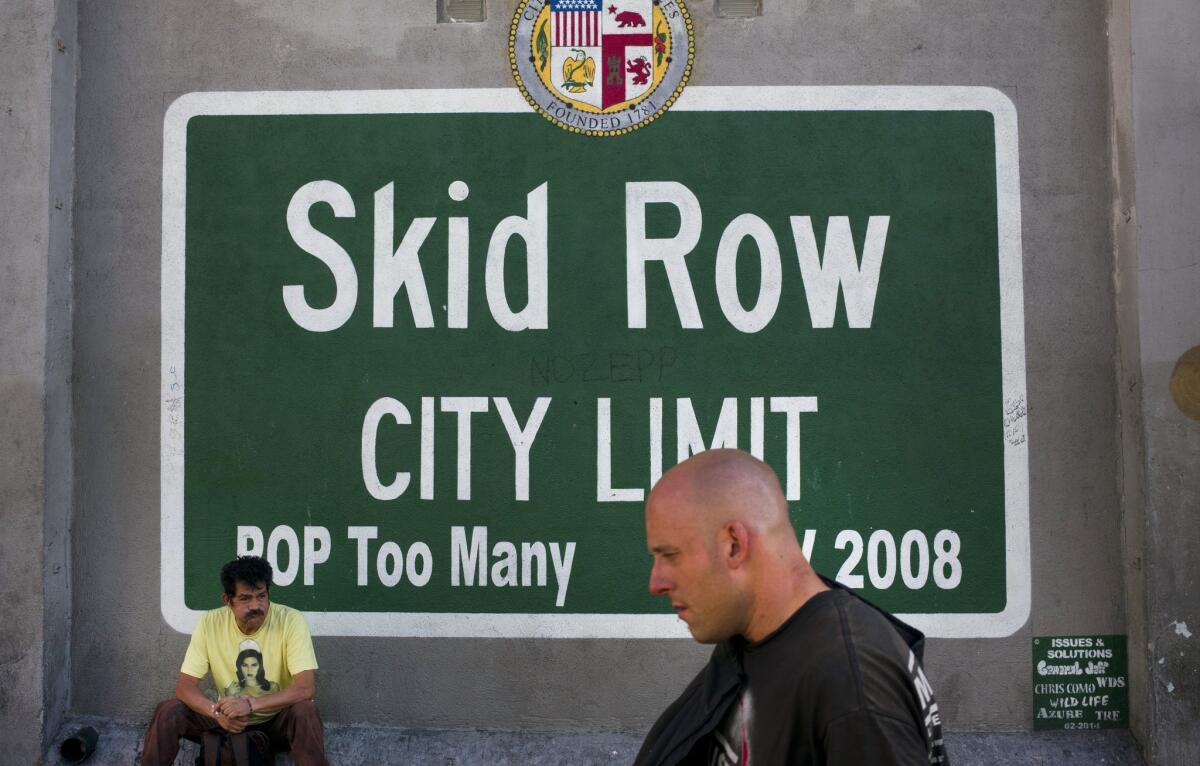

A man walks past a sign painted on a building in the Skid Row area of downtown Los Angeles on Nov. 17.

- Share via

Some myths about homelessness get repeated so often that they become accepted as true. But with more than 31,000 people sleeping in our parks and on our sidewalks every night here in Los Angeles County, we cannot allow fallacies to drive our homeless policies.

“Some people just want to live on the street” is perhaps the most dangerous myth about homelessness. Yes, some people resist moving into short-term shelters because that may require separating family members, losing one’s belongings, or submitting to religious proselytizing or demoralizing rules. But that is not the same as wanting to sleep outdoors.

Study after study confirms that money spent providing housing and services to those who are homeless (or at high risk of it) is recouped on medical care, policing and prisons.

If living without shelter is perceived as just a poor personal choice, punitive law enforcement approaches may seem reasonable. But they are not. Aggressive ticketing for loitering or jaywalking, bans against living in vehicles and sweeps of encampments criminalize daily life for those who have no place to go.

Almost everyone will agree to come inside if they are approached respectfully and offered actual housing, not just temporary shelter. Perhaps the clearest repudiation of the housing-resistance myth is Los Angeles County’s Project 50. Begun in late 2007, it sought to house the most vulnerable and chronically homeless adults living on skid row. Four years later, only 20 participants had left the project and 94 people were still living in stable housing.

A second, related myth: “People choose L.A. as a place to be homeless because of the warm weather.” Although many people move to Southern California for its climate, people who are homeless are no more likely to do so than others. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority found that only 7% of people who are homeless arrived in the county less than a year ago. By comparison, 8.5% of all L.A. County residents have lived here less than a year, according to the Census Bureau. People who are homeless are as solidly Angeleno as everyone else here. We did not import this crisis, nor can we export it.

“Most homeless people are mentally ill” is a third widespread misconception. In Los Angeles County’s most recent homeless count, 28% of those surveyed self-identified as struggling with mental health issues.

Mental illness is just one of many factors contributing to homelessness. People who are homeless most frequently identify the loss of a job, eviction and the high cost of housing as causing their homelessness. Consider that from 2000 to 2013, the median rent for an apartment in Los Angeles increased 27% while renters’ median income fell 7%.

The mentally ill need and deserve better treatment. But homelessness is primarily a symptom of poverty. In Los Angeles County, 289,144 people spend 90% of their income on rent and have household incomes that don’t even reach halfway to the poverty line. These families live on the precipice of homelessness.

“Homelessness is too expensive and complex to solve” is the final defeatist lie. The city of Los Angeles spends more than $100 million a year failing to deal with homelessness. One out of every seven people arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department is homeless. Last year, the L.A. Fire Department spent $2.4 million providing 2,209 ambulance rides to just 40 individuals — most of whom were homeless.

Study after study confirms that money spent providing housing and services to those who are homeless (or at high risk of it) is recouped on medical care, policing and prisons. In 2013, an Economic Roundtable study found that every $1 that Los Angeles spent on permanent supportive housing for the most costly homeless individuals reduced public costs $2 in the first year and $6 in subsequent years. An analysis of Project 50 from 2008 to 2010 determined the project cost $3.045 million, but saved $3.284 million.

Homelessness isn’t too expensive to solve; it’s too expensive not to solve.

We know what it takes to end homelessness. We know that raising incomes and creating more affordable housing ends homelessness. We know that providing rent subsidies, legal assistance and social workers to families facing eviction ends homelessness. We know that intervening early when people do land on the streets ends homelessness. We know that permanent supportive housing for the most chronic cases ends homelessness.

Homelessness is not inevitable. But we will not solve it until all of us — including our city and county leaders — move beyond persistent myths. We know how to dramatically decrease the number of people living and dying on our streets. The time has come to embrace these solutions and bring them to scale.

Adam Murray is the executive director of Inner City Law Center, which serves homeless and working poor clients from its office on skid row.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.