A love letter to the love letter

- Share via

For the last couple of years I have been writing a love letter to the love letter, a pleasurably nostalgic if doomed task. I’ve been pondering what we stand to lose if we abandon pen and stamps forever and just stick to email and social media. How much easier life would be: No fretting about festive greetings cards; minimal delay between sad news and the digital condolence note. And of course in our dotage we’d spend many tear-stained hours grasping all those old love emails to our breast.

We are not there yet, but surely it’s not long now. Those of us who still write letters know that we are a dying breed. To teenagers, it’s as if we still rode on steam trains.

But how much we stand to lose. These days, the arrival of a letter, rare as this is, is a gift in itself. As a form of communication, it has withstood everything we’ve thrown at it for 2,000 years, from the deepest emotions to the cattiest witticisms, from the only written description of the eruption of Vesuvius to the finest pen-and-ink sketches of great artists. Digital alternatives, so open to abuse and prying, really can’t compete in matters of art or the human heart.

YEAR IN REVIEW: 10 tips for a better life from The Times’ Op-Ed pages in 2013

Searching for solace from this imminent loss (a deficit both to family historians and biographers), I found it in abundance among the correspondence of our most celebrated poets. So let us imagine it is November 1820, and John Keats is unwell. He is traveling from Naples to Rome in search of a milder climate and respite from the London fog, but his prognosis is grim and his tuberculosis has taken a fatal hold. To top it all, he is homesick and lovelorn, desperately missing his love, Fanny Brawne. He resolves not to write to her directly (too painful), but he writes often about her to Charles Brown, his good friend in London.

“The persuasion that I shall see her no more will kill me.... My dear Brown, I should have had her when I was in health, and I should have remained well. I can bear to die — I cannot bear to leave her. Oh, God! God! God!”

Keats died three months later at the age of 25. What we know of him beyond the poetry derives principally from his letters, a cascade of insight into an impressionable and intoxicating mind.

And now let’s ask ourselves this: How would his missives have appeared had they been emails? Would they have been as considered or emotional? Would they have carried (as did his scratchy letters) as much progressive insight into the manufacture of his poetry? Would they have been weighty enough to carry his notions of “Negative Capability” and his “Mansion of Many Apartments”? And would they have survived at all, to be pored over and admired by scholars and fans?

The answer, I suggest, is no. Just as Emily Dickinson wouldn’t have written her wonderful, coquettish letters about her formative verse in any other medium, possessed of the slow cerebral whirring required when sitting down for an hour or two at a desk and taking in the week’s events with the soul-searching almost invariably lacking from instant messaging. (And where would Jane Austen’s novels be without the dramatic turns provided by letters on almost every page?)

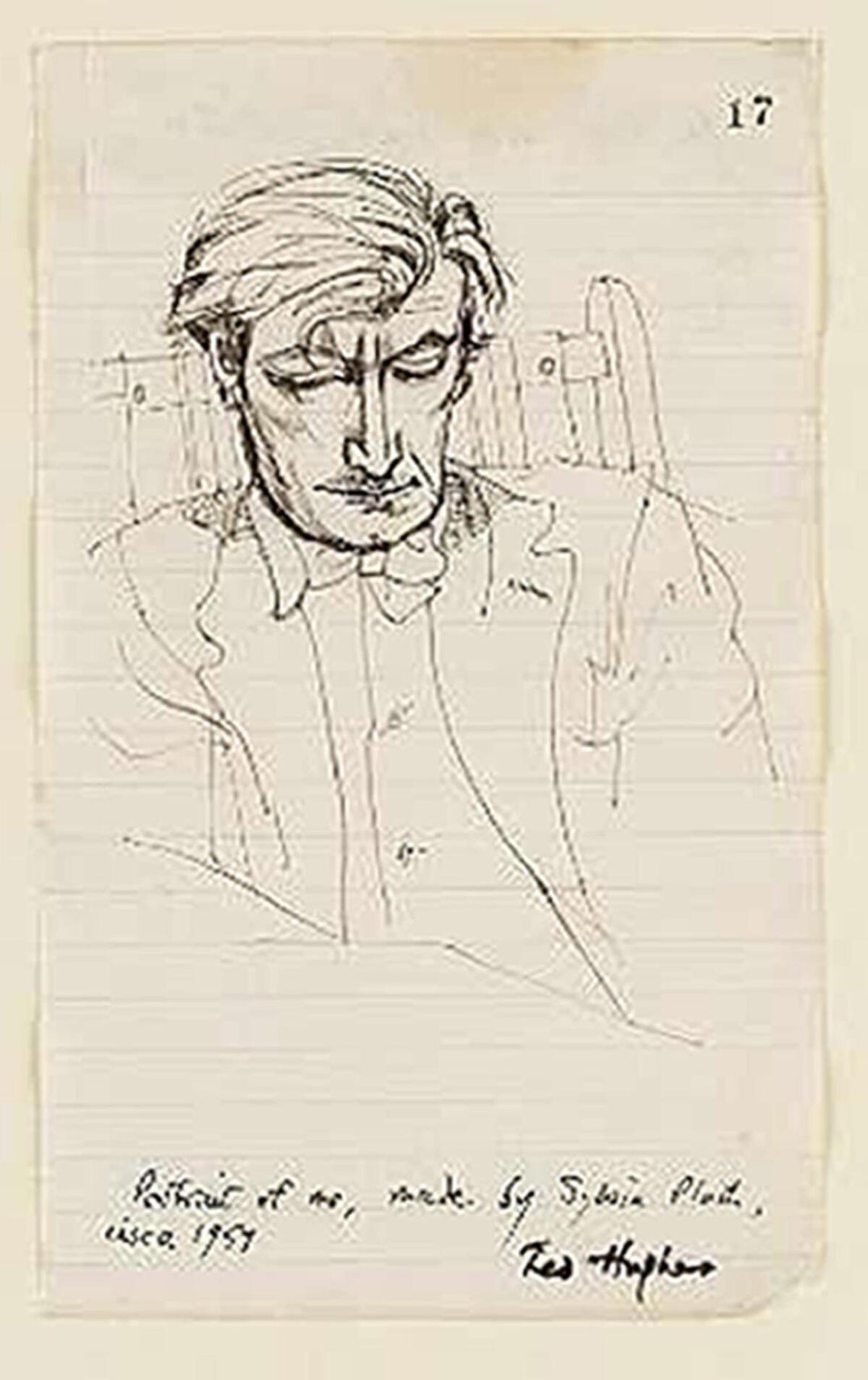

My favorite poet-as-letter-writer is my fellow countryman Ted Hughes. Hughes was once sent a computer by his publishers, Faber & Faber. Hughes was having none of it; he would continue to write only by hand.

His editor told me that he was actually rather glad at the rejection. Hughes’ letters were wonderfully generous and would have appeared far too rigid and forced in any other format. In 1975, for example, he wrote to his daughter, Frieda, at school, describing his summer activities in Devon.

“The rain came just as we were finishing loading the bales,” he recorded. “We had a wild rush to get them in … bales into the horsebox, bales into our ears, bales into the backs of our necks, bales in our boots, bales down our shirts. So we tottered home towering & trembling & tilting & toppling & teetering. And there in front of us was some other tractor creeping along with a trailer loaded twice as high as ours, like a skyscraper. All over the countryside there were desperate tractors crawling home under impossible last loads in the very green rain.”

And if we replace simple letters with their instant always-on alternatives, we relinquish so much epistolary architecture too. The elegant opening address and sign-off, the politeness of tone and the correct grammar and spelling. And before this there is the nice flowing pen and the stationery, and after it the scuttle for the stamp and the rush to the last post. And if we manage all this, we may find the effort is repaid, with a letter back and a personal connection that is reassuringly human.

Are we too late to fight back? I hope not. We could begin, perhaps, with proper thank-you notes for all those holiday presents. And next year we may find our gratitude rewarded.

Simon Garfield is the author of, most recently, “To The Letter: A Celebration of the Lost Art of Letter Writing.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.