Op-Ed: In praise of California’s (disappearing) funky beach joints

- Share via

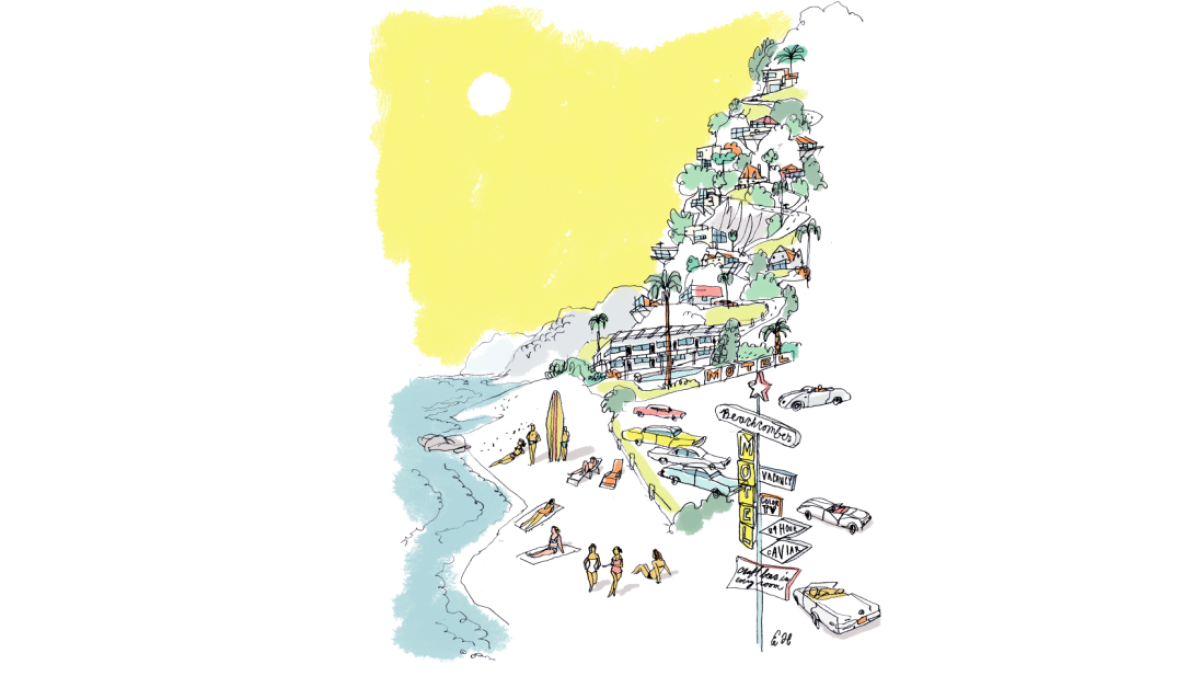

The first time I stepped into San Clemente’s Beachcomber Motel, the hairs on my neck rose with deja vu. The low-slung Spanish building, the tiny rooms with Venetian blinds and picture windows, the kitchenette with its lemon-chiffon tile, the black night and crashing surf — I felt transported into a 1950s noir movie about a dame who holes up with her gangster lover in a sleepy beach town after a big heist.

The fact that I had two toddlers, a respectable husband and a minivan only made the fantasy more delicious. The price was right too — just north of $100 for a room for four perched on a cliff overlooking the Pacific.

Years later, the Beachcomber still stands, but it’s been upgraded to an inn with king-sized beds, flat-screen TVs and studios that run $335 on high-summer Saturday nights.

I’m happy it’s still flourishing along our Golden Coast, where so many rustic beach spots have fallen victim to luxury redevelopment. And I don’t begrudge its owners for raising prices to what the market will bear. But I mourn the passing of an era when people without a lot of money could escape the heat of their valleys and suburbs and spend a few nights living like kings at the beach.

The coast used to be dotted with family-owned establishments that offered a taste of oceanfront living without rock star prices. But now I’m struck by how endangered this species is and how much less picturesque and egalitarian our shores become each time a homey fish joint or bungalow motel gives way to a hulking luxury hotel and fancy restaurant.

I’m not the only one feeling elegiac. Natives and longtime locals get a pensive gleam reminiscing about summer beach spots now relegated to memory and faded Polaroids. Then they lower their voices and tick off their faves that remain, like Walker’s Cafe, a scruffy biker bar on the cliffs of Point Fermin Park in San Pedro that offers unparalleled views to Catalina Island.

But the Universal CityWalk-ification of the coastline rolls on.

On road trips up the Central Coast, we always used to stop at a no-frills fish shack in Avila Beach called Pete’s Pierside Cafe. We adults ate plate after plate of velvety sashimi that probably came off the fishing boats that morning, while the kids gobbled tacos and marveled at the sea lions lounging on the pier’s lower deck, so close you could see seawater quivering on their whiskers. A few weeks ago, as my husband pulled up to the pier, he saw only a pile of rubble. It was the familiar sad refrain: In late 2013, Pete’s lost its lease and so, after 36 years, another coastal institution was no more.

Sometimes I wish there was a state agency devoted to buying these landmarks and keeping them running.

Instead, Larry Ellison of Oracle paid $20 million for the homey Casa Malibu Inn, shut it down last year and plans to reopen it as a high-end Japanese-style hotel.

David Geffen — notorious for locking the public out of access to the public beach that fronts his mansion — bought the Malibu Beach Inn down the road and renovated it into a luxe hotel that outprices most Angelenos.

I suppose the way these guys figure it, if the proles want ocean views, let them stay at campsites and RV parks that thankfully survive. And we do!

Still, we lose more than real estate when these places get torn down or priced out of the reach of regular people. We lose part of our collective soul, the unpretentious laid-back beach culture that weaves through the myths and stories we tell ourselves — the Endless Summer where we eat messy burritos at beach huts in flip-flops and T-shirts and prop wet towels and boogie boards against the weathered wood verandas before rinsing off under rickety outdoor showers and cracking a beer.

These vanquished landmarks were rustic and weathered like driftwood, and so were the people who ran them. They were the epitome of democracy because you didn’t need a gold card, designer clothes or fancy friends to get in the door. They were the essence of the Southern California dream. We should all lament their passing.

Denise Hamilton is an L.A. native, Fulbright scholar, former L.A. Times reporter and award-winning crime novelist. www.denisehamilton.com

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.