The American Revolution shows us how sad and thin Trump’s vision of the country is

- Share via

On July 4, 1970, President Nixon tried to claim America’s birthday for his “silent majority” by hosting Honor America Day in Washington, D.C.

It didn’t go well.

Crowds of Nixon supporters clashed with antiwar demonstrators, hippies swam naked in the reflecting pool, and the bitter divisions of that era ruined what has traditionally been a star-spangled but lighthearted day for hotdogs and baseball.

After nearly a half-century of nonpartisan Independence Days, President Trump is taking a page from Nixon’s playbook by hosting a Fourth of July “Salute to America” rally. “HOLD THE DATE!” he tweeted earlier this year, promising a “Major fireworks display, entertainment, and an address by your favorite President, me!”

We can also expect a story about the American Revolution that sounds much like the one featured in 1970, a narrative of our country’s founding that underpins Trump’s politics just as it did Nixon’s. You’ve heard it before.

For all its bluster about America’s exceptional role in history, this tale of national creation is actually quite tepid.

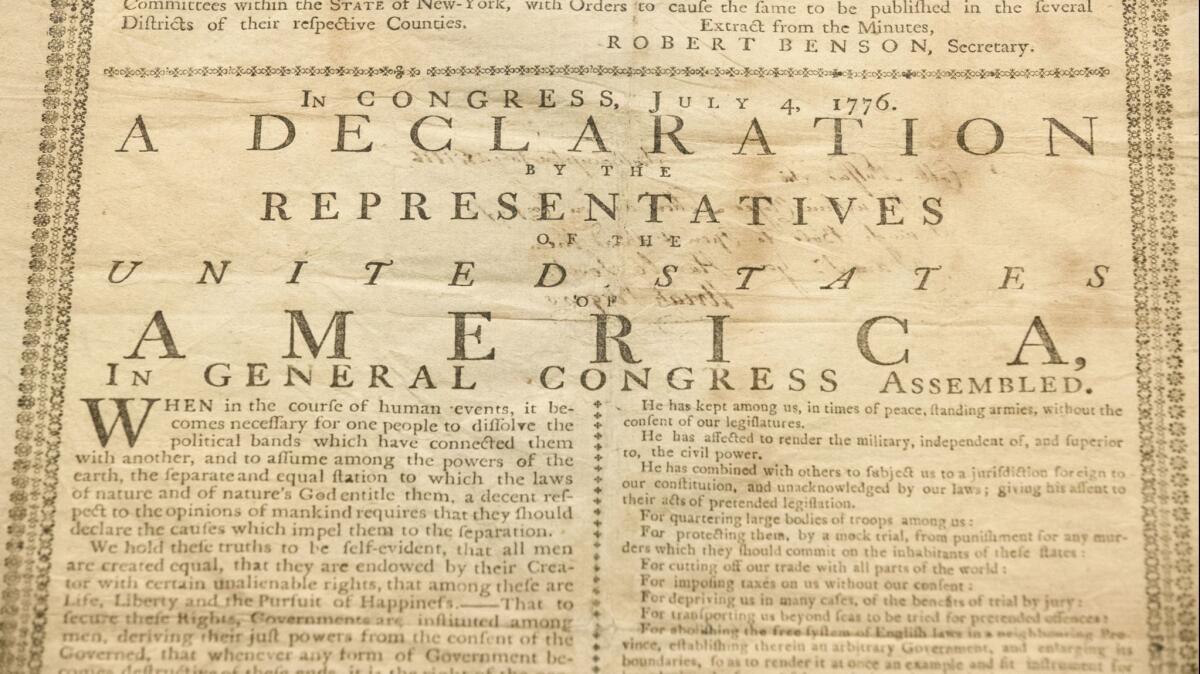

The story begins with a group of virtuous colonists, who began to protest King George III’s taxes and regulations in 1763. Eventually they had to do battle, producing two great documents along the way. One was the Declaration of Independence, released July 4, 1776, to inspire their new country, the United States of America. The other was the U.S. Constitution, released Sept. 17, 1787, to organize that country.

And that was that. Americans had no more need to protest or rebel, because their new government secured their God-given right to pursue happiness. Sometimes they had to “perfect” their union, but basically they rode off into the sunset, toward a Manifest Destiny of continental and then global greatness.

For all its bluster about America’s exceptional role in history, this tale of national creation is actually quite tepid. It assumes that the patriots simply wanted to keep what they already had — that they resolved to stop foreign impositions, not to revolutionize colonial society. It suggests that they were both united and conservative, not at all like wild-eyed French or Russian revolutionaries.

This recounting of the American Revolution isn’t exactly wrong. It’s just profoundly incomplete, because it leaves out the revolutionary part.

The colonial protests of the 1760s and early 1770s had many targets besides tea and taxes. North Carolina squatters attacked lawyers and landlords. South Carolina slaves alarmed their patriot owners by demanding “Liberty!” Baptists and freethinkers condemned elite Anglicans. Before writing “Common Sense,” Thomas Paine denounced imperialism in Asia and slave trading in Africa. “My country is the whole world,” he later declared, “and my religion is to do good.”

Hopes and plans for the new United States went far beyond separation from London. In 1780, the Massachusetts assembly seriously thought about confiscating estates larger than a thousand acres in order to foster equality. That same year, Pennsylvania lawmakers passed a gradual emancipation law, noting that the struggle against Britain had opened their hearts to “men of all conditions and nations.” Black slaves in northern towns walked away from their owners, and courts refused to send them back.

Virginia abolished aristocratic land tenures. Six states tried to ban English common law. Liberal reformers denounced “cruel and unusual” criminal codes as well as corporal punishment at home and school. Duly elected governors rather than crown appointees now shared power with larger, more democratic assemblies.

No single ideology drove these changes. Many revolutionaries took their inspiration from the Bible, while others called religion a farce. Some sounded like the radical “Levellers” of 17th century England, raging against privilege in the name of equality. Others preferred the reasoning of the 18th century Enlightenment, citing Swiss diplomats and French philosophers as a guide to progress. At least 20% of the colonials backed the king, and a similar number tried to stay neutral.

In short, the American Revolution was a genuine revolution — a period of dramatic and unplanned changes. It was chaotic and violent, forcing at least 60,000 Loyalists to flee to England, the Caribbean and Canada. It was a calamity for indigenous peoples and black Americans who lived south of Pennsylvania. Without the crown restraining them, white settlers and speculators charged into the West, often to grow cotton with enslaved workers.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Other vulnerable people also lost customary rights. For example, a battered wife in colonial America could seek protection from her husband in the name of “the King’s peace.” After all, she was a subject just like he was. But in the new United States she was regarded as a noncitizen, a mere dependent in an independence-crazed country.

Nonetheless, the revolution gave rise to a healthy tendency to demand new rights and reject old rules. It encouraged cheekiness. Indeed, British visitors to the “land of republican liberty and equality” saw the archetypal American of the early 1800s as the common servant girl who when asked to fetch her master replied tartly, “I have no master.”

Now more than ever, we Americans need to recall how daring we once were. We need to embrace our revolutionary roots, warts and all, and realize that they reached out in all kinds of directions, to all kinds of futures.

Remembering and sharing bigger, braver stories about how our country came to be might also help us, in these dark times, to push back at our president’s thin, cruel notion of what America is — and should be.

J.M. Opal, who is an American, teaches in the department of history and classical studies at McGill University in Montreal.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.