There’s no magic bullet for Alzheimer’s, but there are ways to keep your brain healthy

- Share via

In recent years, one promising Alzheimer’s drug after another has failed to produce results in clinical trials. At the same time, the growing number of older adults with cognitive problems is reaching a crisis point. In 2018, there were 5.7 million people in the United States living with Alzheimer’s disease. That number is projected to grow to 13.8 million by 2050, threatening to overwhelm the U.S. healthcare system.

One problem with the search for treatments to date has been our limited understanding of what causes dementia. In 1906, when Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist, first described a patient with an unusual disease that caused her mental deterioration and premature death at 55, he noticed accumulations of plaques on her brain that had previously been found only in much older, senile patients.

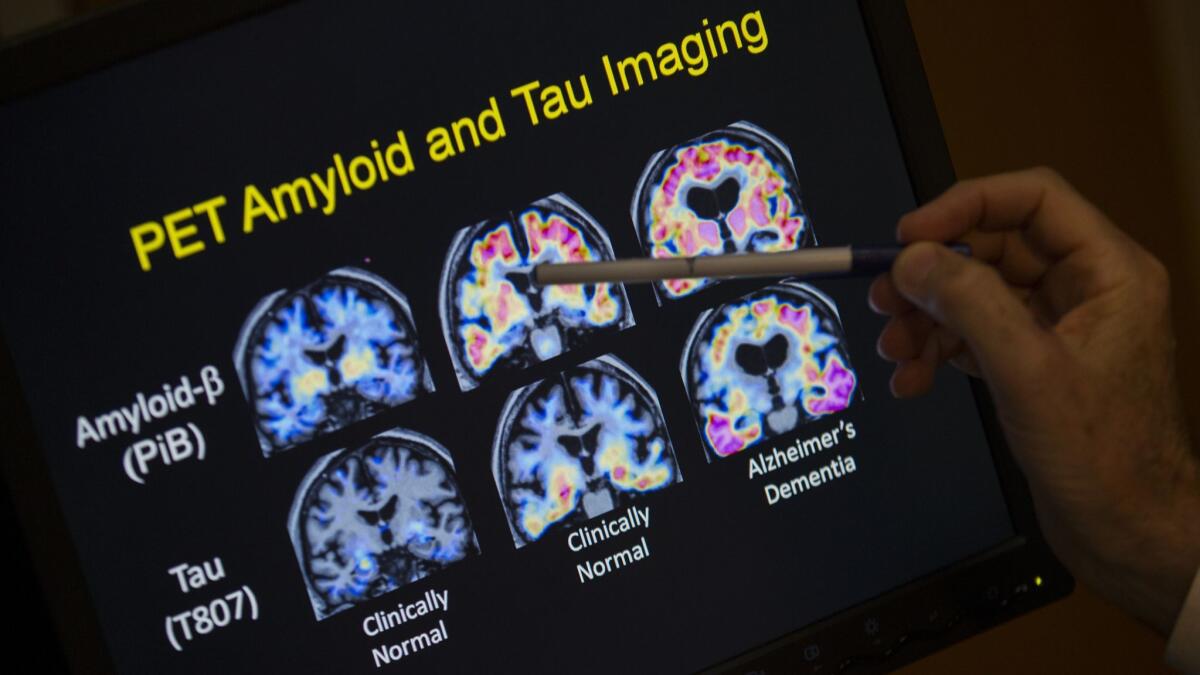

Working from that starting point, scientists began diligently looking for the substances causing the brain changes. In 1984, George Glenner identified a protein called amyloid that builds up in the plaques of Alzheimer patients’ brains.

For the past three decades, the bulk of dementia drug development has been based on that discovery. New drugs have been aimed at decreasing the amount of amyloid in the brain, and some were successful in doing so. The problem was that even with lowered levels of amyloid, memory loss persisted, according to two papers published in 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

High blood pressure can begin as early as age 40 and can be a major cause of brain damage if poorly controlled.

The failures have made clear that amyloid is only part of the problem and that research must also focus on other factors contributing to memory loss.

Fortunately, we have clues. One dates back to a 1997 study by David Snowdon and his colleagues at the University of Kentucky. Snowdon recruited 678 members of the Roman Catholic School Sisters of Notre Dame, an order of non-cloistered nuns who taught children in different parts of the country. He tracked the sisters to see which of them developed dementia and then examined their brains after they died.

The sisters were an excellent cohort for research because of the similarities in their lifestyles and because each woman’s medical history could be matched with extensive records kept by the order. This rich information continues to reveal new indicators for brain health later in life. Some of the brains Snowdon studied had amyloid, the pathological indicator of Alzheimer’s disease, some had signs of vascular disease, and some had evidence of both. The sisters who had amyloid plaques and vascular problems in combination were far likelier to have lost cognitive function when they were alive.

The results of that study were ignored for many years because of the singular focus on amyloid. But researchers are now looking back at the so-called “nun study” for new scientific insights into this terrible affliction.

Several large autopsy investigations published recently from the National Institute on Aging’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers have dovetailed with Snowdon’s findings, demonstrating that many patients who displayed symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease while alive had accumulations of amyloid as well as other markers of brain disease. A large percentage of those patients had cerebrovascular — or stroke-related — changes in their brains along with the amyloid. The autopsies showed that patients with more cognitive impairment in life were more likely to have both amyloid and cerebrovascular brain damage.

With the decline of the amyloid hypothesis as the dominant theory about what causes Alzheimer’s, the emphasis is shifting to the vascular system. Hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, smoking and sleep apnea can all damage blood vessels and increase the risk of small strokes, which have emerged as a major co-factor that adversely affects cognition in old age.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

The importance of this realization is that, even as researchers continue to search for a definitive cure for Alzheimer’s, we also have something today to offer patients hoping to avoid or mitigate dementia: lowering vascular risk factors. High blood pressure, for example, can begin as early as age 40 and can be a major cause of brain damage if poorly controlled. But we have effective treatments.

Many vascular problems can be reduced with exercise, and there is some evidence that moving itself can have a beneficial impact on memory. One recent study done at Einstein College of Medicine found that dancing three times a week could slow the advancement of Alzheimer’s, for example. Early diagnosis and treatment of problems like sleep apnea and diabetes also can help.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle and aggressively treating known vascular problems may not be the silver bullet for attacking dementia that we would like, but it’s becoming increasingly obvious that they are a key part of what’s essential to preserving a healthy brain long into old age.

Gary Rosenberg is a physician and director of the University of New Mexico’s Memory and Aging Center. He is also a professor and former chairman of neurology department at the UNM Health Sciences Center.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.