Andrew Yang seems invisible to the mainstream media — just like most Asian Americans

- Share via

Asian Americans are often invisible in American culture, and judging by the experience of presidential candidate Andrew Yang, even more so in politics.

Many Asian Americans will relate: White people regularly cut ahead of me in line and then are surprised when I call them out. My Korean American assistant recently reported that a man tried to walk through her on the sidewalk as if she wasn’t there. An invitation on Facebook to talk about such invisibility filled up within minutes, with many Asian Americans saying that being ignored or dismissed happens on a daily basis.

For the record:

10:47 a.m. Dec. 1, 2019An earlier version of this story referred to Michael Bennet as a tech billionaire. He is not a billionaire.

Despite Andrew Yang qualifying for every debate so far, media outlets have left him out of various graphics so many times, a supporter created a visual history on Twitter accompanied by a #YangMediaBlackout hashtag on social media, believing this erasure is more than coincidence. Watchdog groups like Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting noted on Twitter, “@AndrewYang is tied for 8th place in the Democratic race — yet he’s not one of the 20 candidates included in @MSNBC‘s candidate graphic.”

Last week, Yang called out MSNBC for omitting him “12+ times” and vowed not to appear on any more MSNBC shows until this is acknowledged.

As a young child in an all-white town, no matter how much I raised my hand in school or tried to make my voice heard, I was ignored so often I learned to use quietness to my advantage. Perceptive teachers would break up whatever raucous clamor that was going on to say, “Let Marie have a turn.” Or they’d clear a path for me to have a chance to say what I wanted — it’s no coincidence the title of my first novel is “Finding My Voice.”

I am not a Yang partisan. I wrote an article in September criticizing him for using model minority stereotypes, such as calling himself “an Asian guy good at math.” But now, I’m wondering if Yang, denied visibility, is deploying stereotypes as a subversive way to actually get visibility.

The question that Asian American actors, and now politicians face, is is it worth it to take on a role that requires you to traffic in stereotypes in order to garner power, enough to put an Asian face in government, in the popular imagination?

There is no way to prove these omissions are related to Yang’s being Asian, but it’s impossible to miss the similarities with the micro (and macro) aggressions people in the Asian American community experience daily.

He has been mixed up with Jerry Yang, the founder of Yahoo.

He has been mixed up with John Yang, of NPR.

He has been mixed up with my friend and fellow writer, Jeff Yang.

Yang’s platform includes automation, cannabis legalization, a value-added tax for tech and, most famously, his plan to create a national basic income or “freedom dividend.” He is not running on foreign policy experience. And yet, during the first debate, the American-born (obviously: he’s running for president) Yang, who is of Taiwanese descent, was asked only two questions. One was about China.

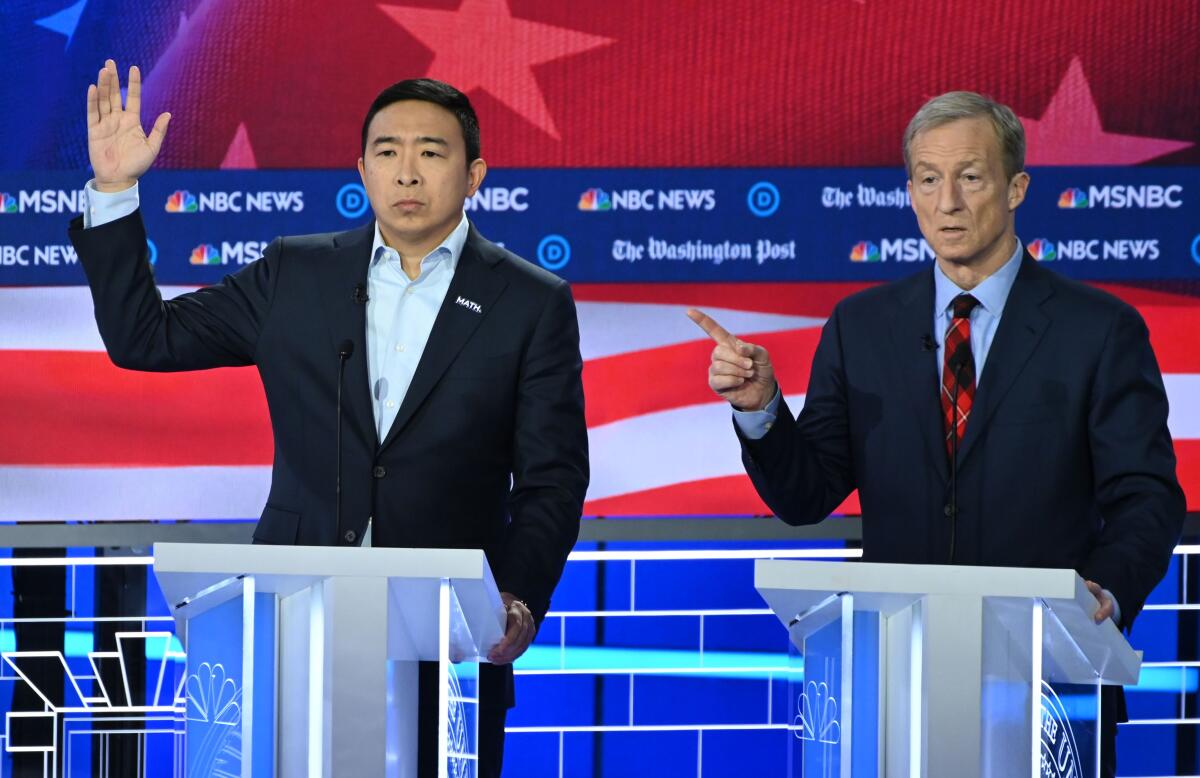

In the most recent debate on Nov. 20, Yang was ignored for 30 minutes before being asked a question. While still on the debate stage Yang tweeted that in four out of five debates, he’s been allotted the least amount of time (6.9 minutes), despite polling ahead of longtime senators Cory Booker and Amy Klobuchar.

The “bamboo ceiling” is a term used in academic circles to describe disadvantages in the job market, where qualified Asian Americans “haven’t been able to climb up the professional ladder,” according to Columbia sociologist Jennifer Lee, author of “The Asian American Achievement Paradox.”

I can’t help but recall during my years in investment banking, how many times I was spoken over, mixed up with the only other Asian person in my department of 200. My ideas were stolen, and I was overlooked for promotions. Invisibility is hard to pin down precisely because you can’t see it. When few Asian Americans are in the top tier of leadership, the visual narrative conveys we are somehow not qualified.

Van Tran, a City University of New York sociologist whose work focuses on Asian Americans and social inequality, characterizes Yang’s candidacy as a tale of two extremes: “Asians from certain groups have exceeded whites in education and income, but are still behind whites in terms of wealth and power.”

I live and work in New York City, where some Asian groups are among the city’s poorest. Yang has been portrayed as an Asian tech zillionaire when his actual net worth, according to the candidates’ own filings, is among the lower tier, near that of Bernie Sanders, while Elizabeth Warren is near the top along with Michael Bennet.

To underscore the idea of Asian American invisibility: Yang is not even the first Asian American candidate to run for president. That was Hiram Fong, a Republican, who ran in 1964 and 1968 but did not have significant support outside his home state of Hawaii. The same went for Patsy Mink, a Democratic congresswoman from Hawaii who ran in 1972. Former Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal sought the Republican nomination in 2016.

Kamala Harris is also running a national campaign. But in the visibility narrative, she has been described by the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times, among others, not as Asian but as the second black woman elected to the U.S. Senate. Her mother is of Tamil Indian descent, and her father is black.

Yang’s candidacy may tell our Asian American children that one day, they, too, can run for president. Or, it may tell them that even if you work hard and play by the rules, there’s only so far you can go. A candidate who can’t be seen can’t win.

Marie Myung-Ok Lee, author of the forthcoming novel “The Evening Hero,” teaches fiction at Columbia University, where she is writer in residence at the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race. @MarieMyungOkLee

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.