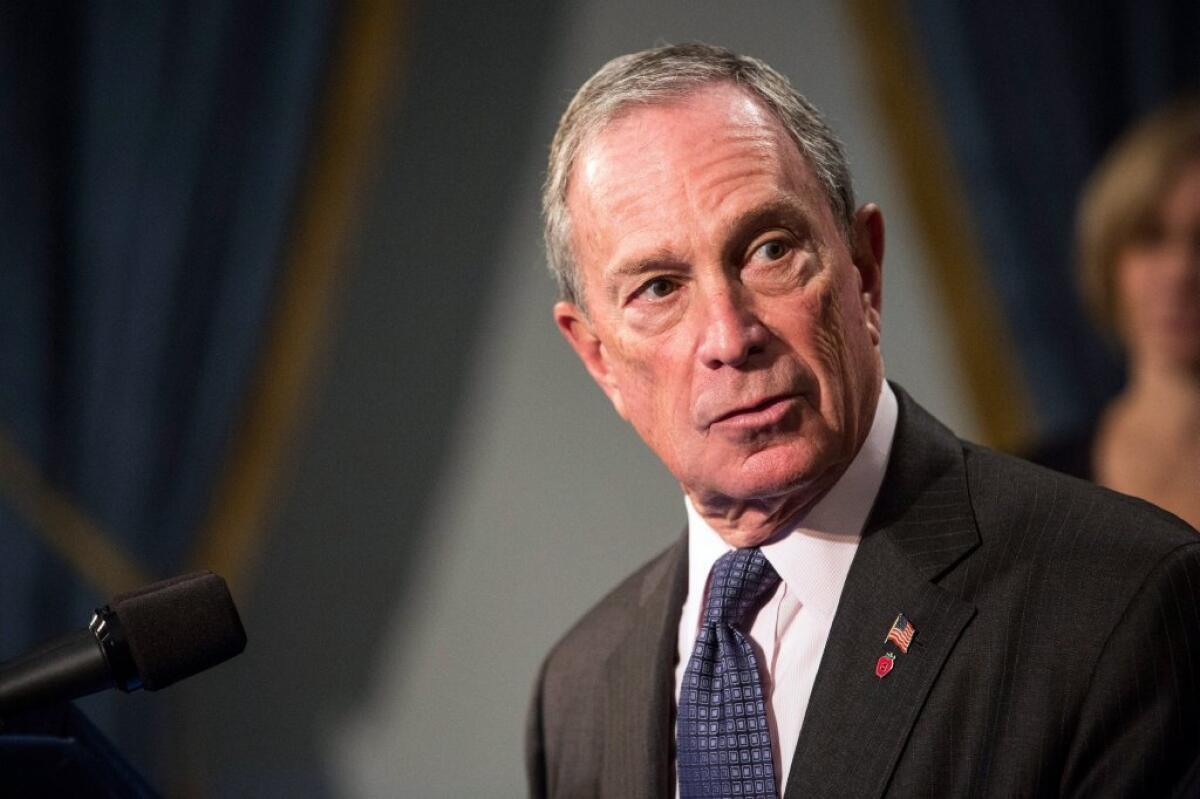

Running against Bloomberg isn’t easy. I know. I was his opponent in the 2001 New York mayoral race

- Share via

Three weeks before the New York mayoral election in November of 2001, I got a call from Mark Mellman, the pollster working on my race against Michael Bloomberg.

“Well, I have good and bad news. The good news is that I’ve never had a client 20 points ahead this late in a campaign who lost. The bad news is that Bloomberg is spending a million dollars a day — not a month but a day — and gaining a point a day.” I quickly did the math and shuddered.

I lost the race by a margin of 50% to 48%, after being outspent $73.9 million to $16.3 million. Ironically, I raised more money than any other U.S. mayoral candidate in history, making 30,000 phone calls and receiving 11,000 contributions. But Mike, who didn’t have to make phone calls, spent the most money ever on a mayoral campaign. He simply wrote checks.

It’s no great surprise that after buying the mayoralty, Bloomberg decided to see if he could do the same with the presidency. There have been other self-funded candidates, of course, and they have all failed. Ross Perot spent $79 million in 1992 and Steve Forbes $60 million in 2000.

But if Mike gets the nomination, his spending already has dwarfed what they spent. He is a bank posing as a person.

It’s hard to imagine a candidate less able to win working-class votes than Michael Bloomberg

I know what that looks like. In the closing weeks of our 2001 race, I had the helpless feeling that there was no strategy that could counter his spending. Everywhere I went I saw or heard a Bloomberg ad: in between innings during the Yankees’ World Series games, on hip-hop stations, on walls in Chinatown, on the rotating billboard at a Knicks game, on mailings that piled up in the lobbies of buildings across the city. He even sent small radios with his name on them to potential voters.

The fact that Bloomberg won in New York in November of 2001, two months after 9/11, is of course quite different from winning a national election in 2020. For one thing, after the attacks, the focus of the election that year changed from the standard city issues of education, crime and housing to a laser focus on safety and security. According to Bloomberg’s media advisor, the late and famous David Garth, the attacks, along with an endorsement from a suddenly revered Mayor Rudy Giuliani, boosted Bloomberg dramatically. Ideally, there will be no such disruptive calamity in 2020.

Also, it was one thing for the then-Republican Bloomberg to sway just enough outer borough Catholics, who generally voted Democratic, to win a general election of New Yorkers in 2001. It’s something entirely different to win a nomination contest where only Democrats are voting, many of them liberal Democrats.

Bloomberg does have some solid liberal credibility — on climate, guns and public health — but on many core issues his record is a liability. He has called Social Security “a Ponzi Scheme.” He opposed raising the minimum wage. He blamed the 2008 Great Recession, in part, on laws against predatory lending. He denounced Obamacare and Dodd-Frank. He enthusiastically endorsed the Bush-Cheney ticket in 2004, was an apologist for the Russian takeover of Crimea and has a long record of making demeaning comments about women. And, as late as last year, he was still advocating a “stop-and-frisk” approach and defending his record on the practice.

Given Bloomberg’s shaky performance in the Nevada debate, it’s hard to feel confident he can reassure liberal Democrats on those issues.

If Bloomberg or Sanders wins the nomination, the Democratic Party might never be the same.

Based on my knowledge of him from our own two debates, as well as his record as mayor and now presidential candidate, I have three questions about his prospects for 2020:

First, will his ability to carpet-bomb the country with ads be enough to overcome the liabilities of his record in the minds of millions of Democrats? Maybe. That certainly worked in New York City in 2001.

Second, if no candidate wins enough delegates to secure a majority, will Bloomberg have a large enough bloc of convention delegates to influence who the party’s choice of a nominee will be on a second or third ballot? Again, the answer is maybe.

Finally, in the event that Bloomberg secured the nomination, would liberals embrace him if Trump is the alternative? Here, there’s no maybe, even for a Warren supporter like me. After four years of watching Trump try to destroy democracy, the answer is yes.

Mark Green served as New York City’s Public Advocate from 1993 to 2001 and was the Democratic nominee for mayor in 2001. He is the founder of @ShadowingTrump and co-author (with Ralph Nader) of the recent book “Fake President: Decoding Trump’s Gaslighting, Corruption and General Bullsh*t.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.