Two LAUSD students sharing a cellphone to find math quizzes? That’s not school

- Share via

When school was dismissed because of the pandemic, 12-year-old Evan, a sixth-grader at 99th Street Elementary School in Watts, used his phone to simulate school as best he could.

“I would find things on the internet like sixth-grade math quizzes,” Evan told me. “I would do that for 30 minutes to an hour, then I would pass the phone to Noah.”

Noah, his 9-year-old brother, is in fourth grade.

Neither boy, according to their mother, Angel Clayton, 32, had been sent home with promised packets of schoolwork that were supposed to last two weeks, until teachers and principals got some training on how to teach from home. Nor were they equipped with laptops.

“They were given nothing,” Clayton said.

The Android phone, passed between the brothers, became their lifeline to academic work.

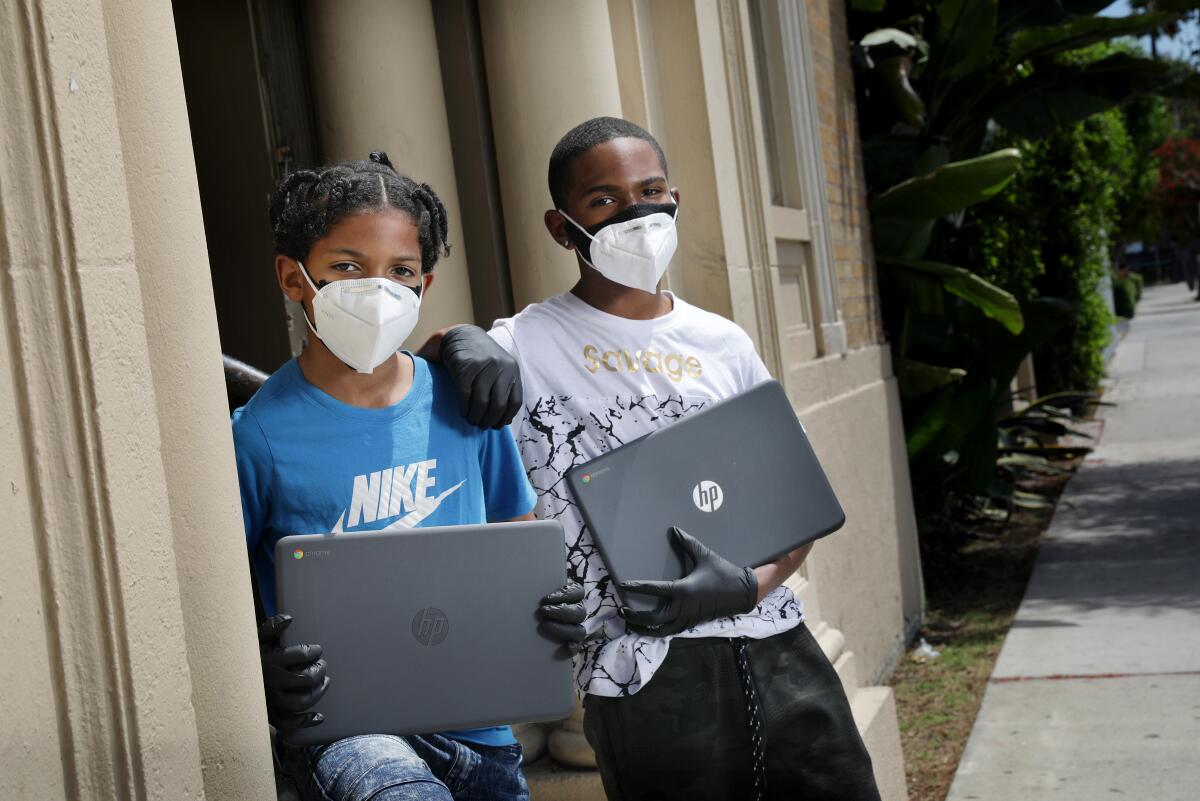

“I wanted to do my work, and he wanted to do his work,” said Evan, as we sat at a table in a conference room at the Watts Community Center on Wednesday morning. Evan, who has asthma, and Noah wore double masks and gloves.

As you can imagine, their mother was not happy to see them relying on one phone.

She had technical trouble helping them log into platforms such as Google Classroom — passwords didn’t work, class codes were incorrect. The boys were losing precious school time.

She said she was surprised to learn that one of their teachers appeared not to be aware of Zoom, the videoconferencing website that is being widely used across the country to simulate classrooms.

Marissa Borden, 99th Street’s principal, said she could not “comment on personnel matters,” but said the school is making every effort to support students with technology and other help.

In the middle of April, a month after school was canceled, the boys were talking to Lara Drino, a prosecutor in the Los Angeles city attorney’s office who spearheaded an intervention program that serves children who have been exposed to gun violence. Drino met the boys last December at the Watts Winter Carnival, where she had an information booth. In April, she visited them outdoors, masked and gloved, with a group of coaches from the Watts Rams, a sports and mentoring program created by officers in the Los Angeles Police Department’s Southeast Division.

“How’s school?” she asked.

She was so taken aback by what they told her that she bought each of them a laptop a few days later.

Now they can use their laptops to attend Zoom classes if their teachers choose to hold them. Many of their classmates have not been so lucky.

In fact, it was not until Friday — two months into the shutdown — that second-graders through sixth-graders at 99th Elementary were scheduled to receive laptops from their school, according to an email they received from their principal. Children in transitional kindergarten, kindergarten and first grade are scheduled to receive theirs on Tuesday.

::

As the Los Angeles Unified School District has scrambled to convert itself from a bricks-and-mortar enterprise, with classrooms, playgrounds and libraries, to an online instructional concern, many thousands of children have found themselves without the tools they need to continue their educations.

That’s not surprising. The emergency decision to suspend classes was made with little warning, and LAUSD schools — especially elementary schools — simply didn’t have enough equipment to provide all of the district’s students with a computer. And even when computers were available, many families didn’t have internet connections.

Obviously, children whose parents could afford laptops and internet service were in much better shape than their less fortunate peers. But most Los Angeles public school students — 80% — come from families that live below the poverty line.

Principals took inventory and dug through school cabinets. I know one who found a cache of outdated tablets from the district’s ill-fated 2013 iPad program, though some parents found they no longer worked and had to return them.

Ten days after schools closed, LAUSD Supt. Austin Beutner announced that the district would spend $100 million on new equipment, including computers and Wi-Fi hot spots for those who lack internet access at home. The district estimated that 200,000 of its approximately 500,000 K-12 students lacked devices to access online instruction from home.

High school students were the top priority, followed by middle-schoolers and elementary students, who were last in line.

By the end of this week, the district says, 98% of its students will be provisioned, although it’s not clear how the district will keep track of who is actually tuning in to school.

Teachers, as it happens, are not required to conduct live online classes.

An agreement struck between the teachers union and the district on April 8 specifies that teachers must work at least four hours a day on “instruction and student support,” which can include phone calls, emails and texts.

“The use of live video is encouraged,” it says, “but shall not be mandatory.”

This is a shame. Live video should be mandatory.

As the parent of a Los Angeles public school fourth-grader, I can tell you that her daily 90-minute Zoom classes have become an important and meaningful part of her day.

While the situation is far from perfect, she is able to maintain an emotional connection to her teacher, her classmates and the academic process itself.

It’s a simulation of normalcy; children raise their hands and are called on, Ms. Johnson reads to them from a book about the Gold Rush, and she chides them for goofing off. Small groups of students gather in “breakout rooms” to work on projects.

The last two months have been a steep learning curve for all of us, and the district has done some magnificent work, both in securing equipment for kids and in feeding struggling families.

But it hasn’t been easy.

Evan’s teacher did not respond to an email requesting comment for this column. On Monday, Angel Clayton received a text from him. The teacher wrote that he had been sick over the weekend, was still feeling under the weather, and would not host any Zoom classes for the week, nor give any new homework.

“Take this time to finish any missing assignments,” he wrote.

There was no mention of a substitute teacher, which Evan found disappointing.

“My online schooling hasn’t been so good,” he said.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.