Corruption in City Hall is nothing new. So, what are we going to do about it?

- Share via

Tuesday’s arrest of L.A. Councilman Jose Huizar marks a long-awaited milestone in a multi-year federal investigation of corruption in L.A. City Hall. Now the question is whether the city’s leaders will dismiss it as an aberration, or have the guts and vision to finally curb the corrupting influence of money in politics.

The assistant director in charge of the FBI’s L.A. field office described Huizar’s operation as a “criminal enterprise [that] sold the city to the highest bidder behind the backs of taxpayers.” The former chair of the City Council’s planning committee, Huizar stands accused of pressuring real estate developers for hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash bribes, political donations and assorted favors in exchange for helping expedite their projects.

And it wasn’t just Huizar. Earlier, his former colleague Mitch Englander pleaded guilty to accepting $15,000 in illegal cash gifts, female escorts, and expensive food and drinks in out-of-town casinos and resorts.

Most of the city’s elected officials — and most of those seeking permits from the city — have not been implicated in the schemes to date. But that’s the problem with corruption. The whiff of it emanating from L.A. City Hall taints everyone who represents or interacts with city government. And it reinforces public cynicism about both politicians and the businesses that seek city approvals.

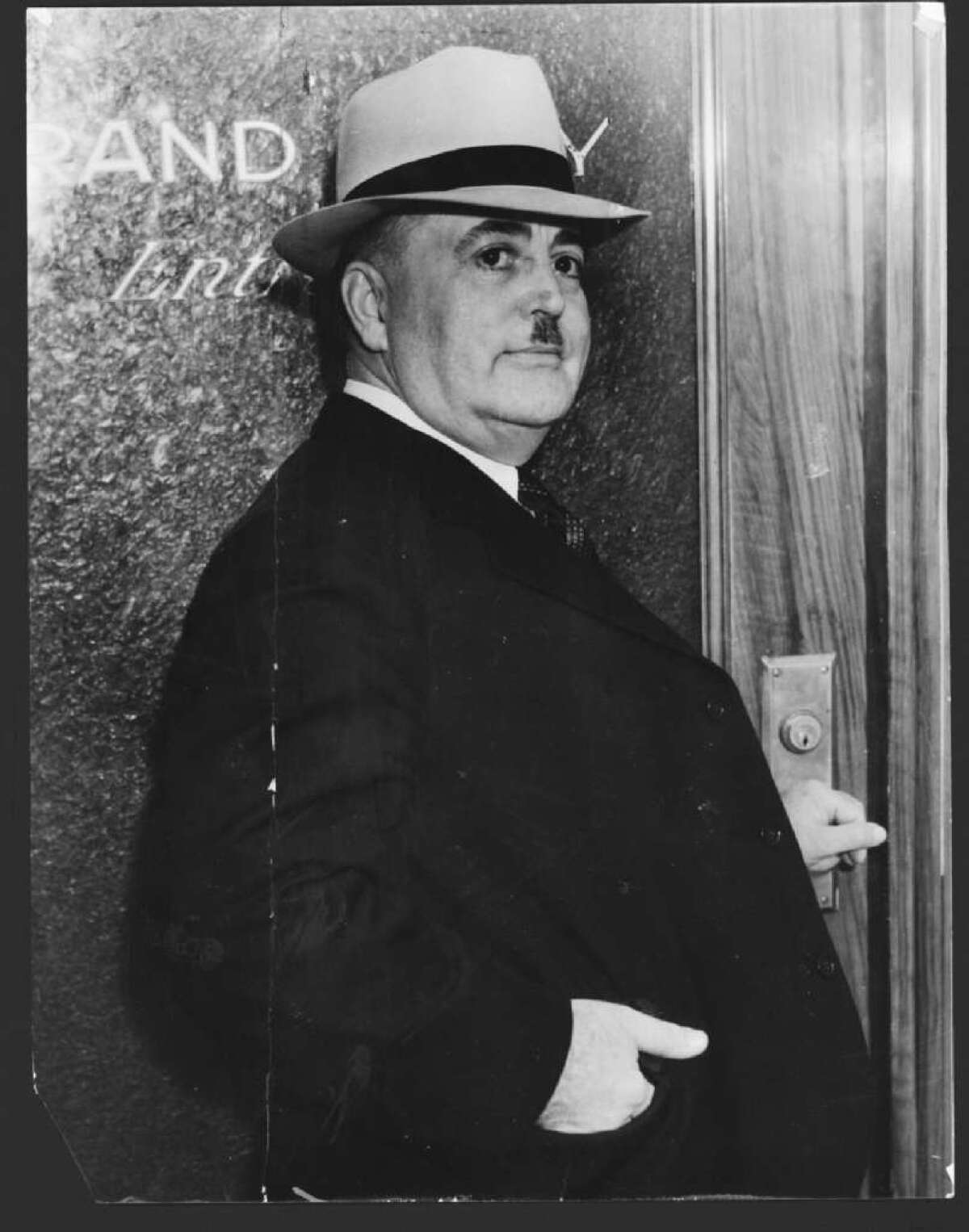

L.A. corruption is, sadly, nothing new. During the early 20th century, the city earned a reputation as one of the most crooked cities in the country. Madams, gamblers, bootleggers and gangsters paid off the whole chain of command, including at times the mayor, City Council members, the district attorney, county supervisors and LAPD Vice Squad officers. The absolute low point may have been during the term of Mayor Frank L. Shaw, where anything and everything was for sale. Disgusted, voters revolted in 1938 and forced Shaw out of office in the city’s only successful recall of a sitting official.

About 50 years later, another mayor of Los Angeles, Tom Bradley, became ensnared in a scandal involving consulting fees he was paid by a local bank. Bradley was arguably the most consequential mayor in L.A. history, responsible for many tangible advances that shaped 21st-century L.A. And his handling of the 1989 incident was very different from Shaw’s. Bradley stepped out in front of the crisis, initiating a process to come up with a solution.

Many of the allegations against Jose Huizar laid out by prosecutors have been described in previous court filings. But there are some new allegations.

The mayor reached outside City Hall to appoint an independent, blue-ribbon commission to propose ethics reforms. He tapped Geoffrey Cowan, a former chair of California Common Cause, to head the commission, and put other civic leaders in supporting roles including then-Cardinal Roger Mahony and former Secretary of State Warren Christopher.

After deliberating for six months, the Cowan Commission agreed on a bold strategy that reached far beyond the conflict-of-interest case that had triggered the process. The group’s report called for a pioneering voluntary system of public financing of campaigns and for campaign spending limits to reduce the need of candidates to constantly raise private donations (frequently from donors doing business with the city).

I served on the City Council at the time, chairing a new ad hoc committee on ethics reform, and it fell to me to try to round up the council votes for the reform package. I learned a bitter lesson about what happens when you ask a political body to reform itself.

Many council members found something to object to. Some questioned why rules for council members should change when it was the mayor who took questionable payments. When the reform package came up for a vote the first time, it fell short of a majority and was pronounced dead. But we kept at it, carefully crafting a few amendments. Another vote was scheduled, and in a dramatic turnaround we cobbled together a majority to put the reforms package on the ballot. Subsequent approval by the voters gave Los Angeles the furthest-reaching municipal ethics and campaign reform law in the country.

Now City Hall is beset with a new generation of unethical conduct. Corruption is an ever-present threat wherever power and money converge, adapting like a virus to changes in a host cell. But that doesn’t mean the people of Los Angeles are helpless to control it.

The city needs once again to get ahead of the corruption. One crucial step would be appointing an inspector general — a fearless enforcer who would be politically independent (not relying upon the mayor or the City Council for a job or operating budget), uninterested in acceptance by “the city family,” and empowered to initiate criminal investigations. At the federal level, President Trump’s recent firings of five inspectors general are an unintended testament to the power of independent watchdogs to shine a spotlight on corruption and waste.

Council member David Ryu, who started calling for a ban on campaign contributions from developers before he was elected four years ago, has introduced two new reform proposals. One would empower an investigator/auditor who could become City Hall’s inspector general. The other would take away the power of the City Council to override decisions of the L.A. City Planning Commission.

Reformers should seize upon the current infection of City Hall’s body politic to embrace these initiatives and come up with others. And if the elected officials fail to act decisively, let’s use the power of the ballot box to replace them with leaders who will. The ensuing debate on cleaning up City Hall could set the reform agenda for the next mayor and council members to be elected in 2022.

Michael Woo was a member of the Los Angeles City Council from 1985 to 1993.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.