California must fix its school inequality problem. Early screening for risk of dyslexia is a start

- Share via

California has received more than $22 billion in new federal funds for public schools since December that have not yet been accounted for in the state’s 2021-22 budget plan. Education leaders in the state are anxiously awaiting Gov. Gavin Newsom’s revision to the budget to see how those funds will be invested in communities and school districts across the state hard hit by the pandemic.

While many are asking when schools will get back to “normal,” we should be working toward a “new normal” of better educational policies that will replace some of the deep-rooted flaws and inequities in public schools, which were exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is an immediate need to address academic learning loss and the mental health needs of students and staff. There is an even bigger need to reinvent strategies of instruction so that the education system is focused on all students and results.

For many in disadvantaged communities, pre-pandemic public education was a ZIP code-based system with uneven opportunities across districts and within schools. In 2019, 63% of low-income — and 68% of Black American — third-graders could not read at grade level.

A great step to ensure that all children are prepared to succeed is early universal screening for risk of dyslexia as proposed by SB 237, a bill introduced by state Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-La Cañada Flintridge). Screening all students in early grades can help teachers and parents address one of the biggest challenges children have to academic success — the failure to read at grade level.

Early screening can identify students at risk of dyslexia and help them as soon as possible, rather than doing nothing and expecting them to “grow out of it.” Instead of waiting for failure, universal screening would push schools to offer earlier support and monitoring for at-risk students.

The cost of failing to learn to read grows each year because of the new information covered in each grade and the pace of brain development. Screening, which can take less than 15 minutes, coupled with evidence-based teaching such as sound-symbol association, word decoding strategies and ensuring each step builds on concepts previously learned have all shown to help students identified as at risk of dyslexia. Early intervention can improve student achievement, save money in costly remediation in later grades and reduce dropout rates.

Students who struggle to read are four times more likely to drop out of high school. In California, the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation reports more than one-half of adult inmates are functionally illiterate. Without early screening for risk of dyslexia at schools, children in families that lack sufficient resources may not be identified in a timely manner or receive the appropriate support.

California is one of only 15 states without a screening law and is behind other states in carrying out evidence-based strategies to help students who have been identified with reading dysfunction and at risk of dyslexia. In 2015, the Legislature passed a law requiring the development of California Dyslexia Guidelines and technical assistance for schools. But the recommendations are voluntary, and only a few school districts in the state use universal screening.

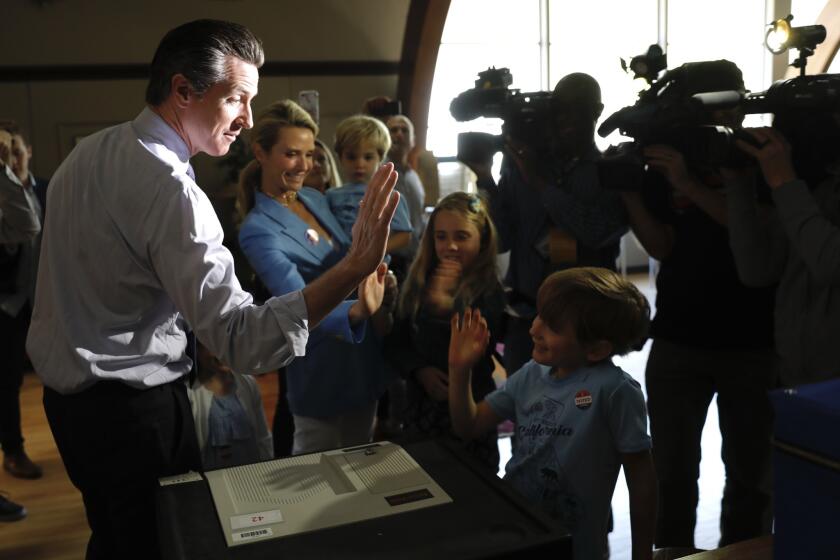

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said that he’s writing a children’s book for kids with dyslexia, a learning disability that affects him and at least one of his children.

As the 2021-22 budget is finalized in the weeks ahead, lawmakers must avoid the approach of first using new money on old programs and only trying new techniques if there are funds left over. Instead of “restore” and “return to normal,” they must reimagine and invest in prevention and equity of opportunity. Policymakers should redesign the system to ensure that all students get the attention and resources they need in the early grades to learn to read. They cannot afford to wait.

With a rare opportunity to improve the trajectory of millions of California kids’ futures, the state should take the long view and correct the educational opportunity gaps that have existed for decades. Back to “normal” isn’t good enough when it comes to our kids’ schooling. This year we have the funds to do something about it.

Contributor: When reading to learn, what works best for students — printed books or digital texts?

The pandemic hastened the rise of digital reading for school assignments. But for most students, print is the most effective way to learn.

Bill Lucia is the president of EdVoice, a nonprofit organization that advocates for policies to improve achievement of all students in California.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.