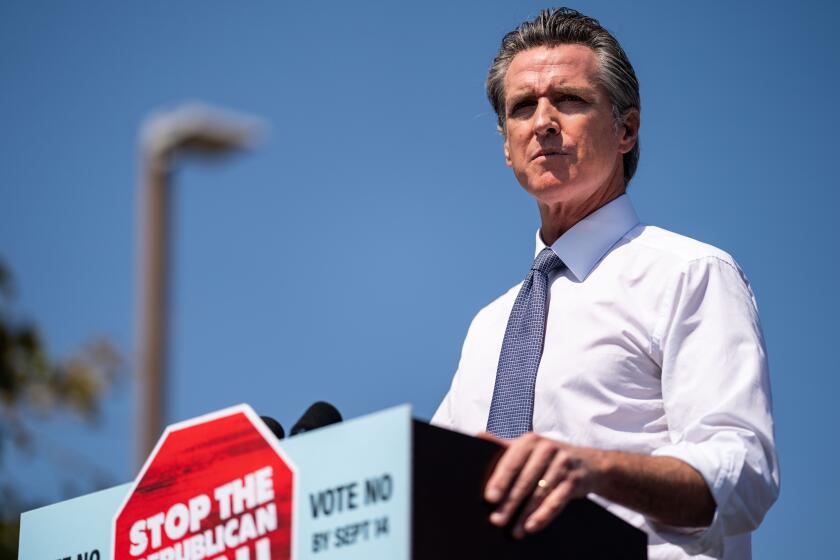

Newsom crushed the recall. Let the phony fraud investigations begin

- Share via

The attempt to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom should never have occurred in the first place.

It did nothing but shred $276 million in taxpayer funds, distract from our real problems — the resurgent COVID-19 virus, homelessness, poverty, drought — and virtually guarantee that Newsom will be reelected in 2022.

The misbegotten effort proved that Republicans, so dramatically outnumbered in California, will go to absurd lengths to undermine a duly elected Democrat. Let the “audits” and the “fraud” investigations begin!

With the recall’s failure, California has dealt another blow to the forces of Trumpism, embodied by Larry Elder, the conservative talk show host and Trump clone, who emerged as the Republican frontrunner among the dozens of candidates vying to replace the governor.

Elder vowed to be the anti-Newsom, promising to overturn mask and vaccine mandates. But unfortunately for him, early exit polls showed that voters’ No. 1 concern was COVID-19, and they mostly approved of the way Newsom has handled it.

Still, Newsom should take this moment to reflect on his shortcomings. Welcome as his victory is, we need to get to the bottom of California’s unemployment department scandal, where fraudsters made off with billions of dollars while deserving Californians were left high and dry on his watch. And we need to know why, exactly, he slashed the budget for wildfire prevention at a moment when the state is going up in smoke.

The recall’s failure also shines an unforgiving light on the shortfalls of the process itself.

When this election is officially settled, our state legislators must find a way to initiate reforms.

Some have suggested the formation of a bipartisan commission charged with developing policy proposals to present to voters. They could do things like raise the number of signatures needed to place a recall on the ballot, which, at 12% of votes cast in the previous gubernatorial election, is indefensibly low. Or allowing a recall only if an elected official has engaged in illegal or unethical behavior.

The election provided California voters an opportunity to judge Gov. Gavin Newsom’s ability to lead the state through the COVID-19 pandemic, a worldwide health crisis that has shattered families and livelihoods.

In July, pollster Mark Baldassare of the Public Policy Institute of California said most California voters support raising the recall bar.

::

For months after the recall campaign launched in February 2020, Newsom seemed to be floating above the fray. He had successfully dubbed the endeavor a “Republican recall” and everyone knows Republicans don’t win statewide campaigns in California. What, me worry?

His steady rise from serving on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to mayor of the city to California lieutenant governor to governor seemed almost preordained. He was elected governor in 2018 with almost 62% of the vote in a state where Trump lost each of his presidential elections by about 30 points.

But the confluence of unpredictable events and self-inflicted wounds meant that Newsom ended up in the fight of his charmed political career.

First, the pandemic hit, and with it, Newsom faced the unforgiving task of weighing public health considerations against the toll that business and school closures would take on Californians.

The governor, as he vowed ad nauseum, met the moment.

He took the responsible, if unpopular steps — ordering lockdowns, school closures and mandating masks, which became outrage triggers for Trump-loving Republicans. Those voters may represent a sore-headed minority in California, but they nevertheless constituted more than 6 million members of the California electorate in 2020. And they were mad.

Still, the recall was suffering from a lack of momentum, and the deadline for obtaining enough signatures to qualify for the ballot was fast approaching.

Just when things looked bleak for recall proponents, two things happened that may have changed the course of events.

On Nov. 6, when Newsom probably thought the recall effort would never make the ballot for lack of signatures, he joined a bunch of lobbyists for a fancy wine-country birthday dinner. As we all know, the guests were unmasked and sitting close at the very moment he was urging Californians to stay in and stay apart.

Newsom quickly apologized for what he called “a bad mistake” and that might have been the end of it.

Unfortunately for him, two days after his apology, on the recall petition deadline of Nov. 17, a judge agreed that the pandemic lockdowns had unfairly crippled signature gathering — and extended the deadline for another four months, until March 17. It gave Newsom’s detractors time to hammer him relentlessly for his pandemic response and his French Laundry folly, neither of which had been on his antagonists’ radar when they began plotting his demise.

::

I watched a documentary airing on the official recall website that chronicled the monthslong effort to gather 1.7 million valid signatures to get the recall on the ballot.

It starred Orrin Heatlie, the retired Yolo County sheriff’s sergeant, who explained that the recall effort was sparked by his frustration with Newsom’s unilateral decision to put a moratorium on the death penalty in California, despite voters twice voting to retain it, and his support for immigrants.

Among the volunteers who came together in scenes around kitchen tables to process petitions was a palpable sense that they were doing God’s work, that they were saving California from a fate worse than Venezuela’s, that Newsom had to be removed from office because he was “the head of the snake,” a tyrant, a dictator, a bully, a would-be king.

“Letting the people intercede in the middle of somebody’s political term is pretty awesome,” said Randy Economy, then a recall spokesman. “It’s kind of the cornerstone of democracy.”

Actually, no, the cornerstone of democracy is free and fair elections.

This recall might have been free and fair, but it was a waste of time, a waste of energy and a waste of money.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.