School safety officers don’t make students feel safe

- Share via

A widespread and justified fear of school shootings exists. The problem with this fear is that the American imagination often conjures a disgruntled teenage boy as the shooter. Instead, most people bringing guns to middle and high school campuses are uniformed officers paid to “patrol” schools. During the 13 years that Long Beach Unified School District employed me as a social science teacher, I witnessed the effects of their armed presence.

School security officers establish a militarized atmosphere. They also create a sense of imprisonment. This adversarial dynamic heightens student stress. At best, a militarized environment makes learning difficult. At worst, it makes learning impossible. When these officers use deadly force against youth, learning grinds to a terrifying halt, turning campuses, and their surrounding neighborhoods, into combat zones.

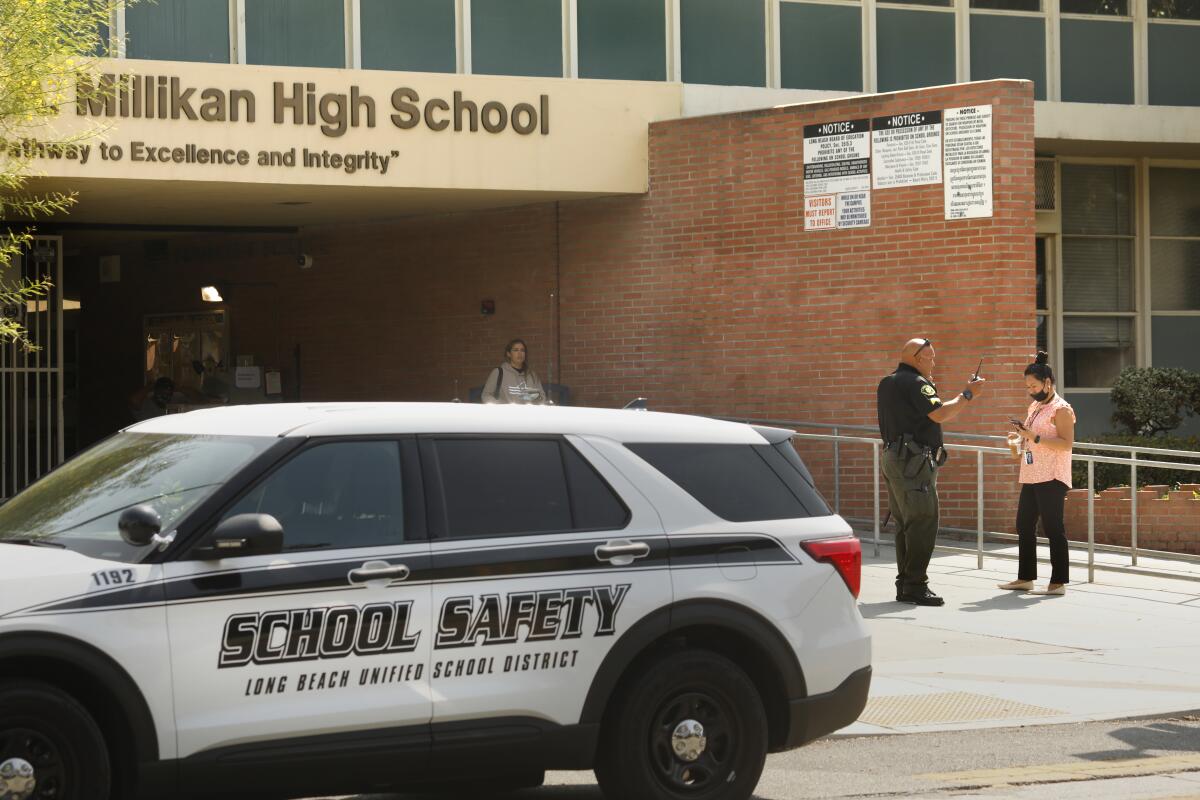

On the afternoon of Sept. 27, an encounter with a Long Beach school safety officer near Millikan High School sent Manuela “Mona” Rodriguez, 18, to the hospital. The officer arrived as young people argued near the corner of Spring Street and Palo Verde. Kids involved in the argument hopped into a car; Rodriguez was a passenger. The officer approached. As they drove away, he fired two shots that hit the car.

In video captured by a student, one hears witnesses screaming.

Rodriguez was struck in the head, leaving her brain dead. Her family announced Friday that she would be removed from life support. Rodriguez’s 5-month-old son will be motherless. During a news conference, her brother Oscar said: “What happened to my sister isn’t right. And we all know it. … She didn’t deserve this. … I don’t even wish death on the person who killed my sister.”

According to their job description, school safety officers are supposed to “think clearly and logically, use good judgment.” However, when faced with an everyday situation — teens behaving rebelliously — a school safety officer chose to discharge his weapon at a moving vehicle filled with youth. This officer not only lethally escalated a situation; he also made a spectacle of executing a child.

One message sent by this killing is that youth risk death for engaging in ordinary teenage activities. It suggests deadly stakes for defying authority. Most teenagers will, at some point during adolescence, defy and disrespect adults. Psychologists call this process individuation. During individuation, kids strive for autonomy, often through predictable and relatively harmless acts of rebellion, such as name-calling or disobeying instructions to stay put.

No child should be terrorized and threatened with lethal violence for engaging in developmentally normal behavior.

Teachers are unarmed, and we regularly face unpleasant behavior from teens. In fact, we expect it and defuse it. It’s up to caring adults to guide young people in learning how to negotiate limits, assert autonomy and cultivate trust. Such guidance occurs only in environments where young people feel safe and cared for. When teachers are perceived as enemies with the power to summon armed officers, trust withers.

The social justice group Black Lives Matter Long Beach recognizes that school militarization degrades the learning environment. In May 2020, representatives of the group met with the district’s superintendent, Jill Baker. They demanded that “LBPD officers and SSOs be removed from schools, because they … carry guns that could be potentially harmful to students.” The board of education agreed to remove three Long Beach Police Department officers from the schools, but allowed school safety officers to remain.

The “physical and psychological safety of over 68,000 students,” according to Black Lives Matter, remains “in clear jeopardy.”

BLM is right. I have witnessed officers behave in ways that students perceived as potentially life-threatening. For example, on two occasions, I observed officers tell students to put away phones. When defied, the officers reached for their guns, as if preparing to draw. I listened as one student pleaded with his classmate: “Put your phone away, man! It’s not worth it!” The officers’ gesture seemed violently absurd. Phones are a nuisance I’ve dealt with countless times. I’ve never reached for a weapon to facilitate compliance.

Such threatening interactions with officers traumatize students. We’ve seen their effects for decades, tragically. Since at least the 1950s, an ominous police presence has been a tool to suppress racial justice movements and enforce school segregation.

Today’s school militarization reaches far beyond Long Beach. Scholar Chelsea Connery describes the problem as countrywide: “In 1975, only 1% of schools reported having police officers on site, but by 2018, approximately 58% of schools had at least one sworn law enforcement official present during the school week.” Some school districts have even received military equipment through a Defense Department program.

Parents rightfully want to know how they may keep youth safe on and off campus. Pressuring school boards to demilitarize campuses and redirect funds to mental health resources will vastly improve learning environments. Armed officers do not keep children safe. While teens rarely bring guns to middle and high school campuses, adults often do — with the imprimatur of the government. They use them to intimidate and kill.

Myriam Gurba, a writer and former teacher in Long Beach, is the author of “Mean.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.