The cyberattack on Los Angeles schools could happen anywhere

- Share via

Education technology enhances classroom learning. It also risks exposing up to 53 million K-12 students nationwide to costly disruptions. As the Los Angeles Unified School District experienced in the last month, learning and basic school functions can grind to a halt if systems aren’t properly secured.

As school districts keep adding technology, they increase the risk of ransomware attacks. Products such as Google’s laptops, assignment apps and writing tools — some of which were already being used in more than half of classrooms as of 2017 — have introduced a wealth of confidential information about students into the tech ecosystem of K-12 schools, on top of data from staff and contractors. The pandemic accelerated use of virtual learning tools that increased schools’ vulnerability, and there’s been an uptick in the frequency and complexity of attacks.

Both affluent and low-income communities are targets. A 2020 report found that although large districts and those serving wealthier communities are most likely to experience a cybersecurity incident, districts with a greater proportion of students in poverty were also likely to be hit, possibly because hackers know those districts receive federal funding to bridge the digital divide.

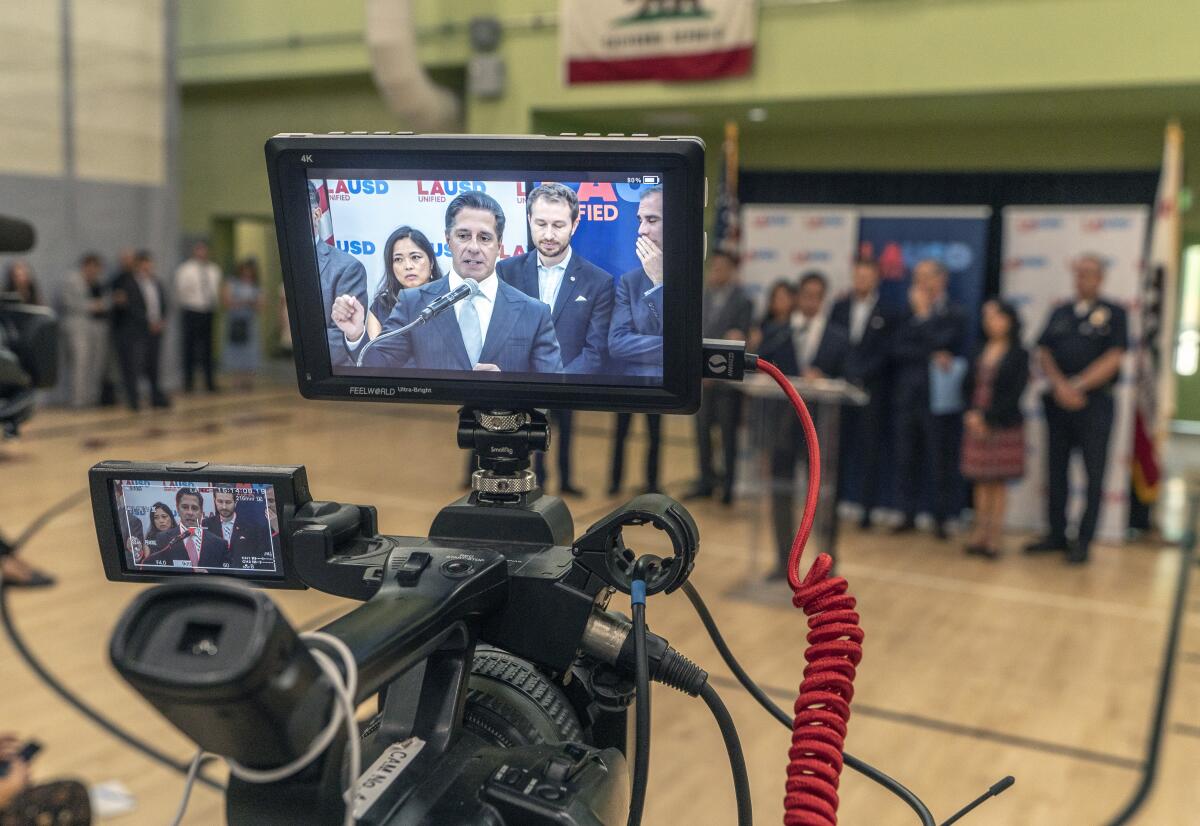

L.A. Unified leaders say people should breathe easier over a hack that was largely unsuccessful, but some experts talk of continued cause for concern.

In the recent L.A. case, hackers launched a ransomware attack over Labor Day weekend, in line with the strategy of “back to school” and holiday attacks that target stressful times when, against FBI advice, administrators may be more likely to pay ransom to restore systems and recover data.

L.A. schools refused to pay ransom, and the hackers responded by releasing district data onto the dark web Oct. 1. Although officials report that relatively few individuals had sensitive data revealed from the attack, the information includes Social Security numbers for what the district said was a “limited” number of facilities contract workers. The attack also led to some disruptions on the first days of school.

These cybersecurity threats aren’t caused just by hackers: Old equipment, reliance on third-party tech contractors, inexperienced staff and a failure to follow basic security protocols can cause breaches. Legacy technology in many schools — past-its-prime IT infrastructure, including hardware, other devices and software — often can’t support modern security needs.

Unfortunately, the very IT professionals contracted to protect computer systems end up causing at least 75% of data breach incidents in public K-12 school districts, data from the last few years show. That’s partly because of a shortage of expert staff who can effectively vet and monitor vendors to ensure that they adequately manage risk and reduce schools’ vulnerabilities. Districts’ reliance on a bunch of different tech vendors means that something, somewhere, is always broken, according to Rotem Iram, chief executive officer and co-founder of At-Bay, a cybersecurity insurance provider in California. And hackers know that’s the case in schools.

Students, teachers and contractors at LAUSD could have sensitive personal information on the dark web. Here are the steps you should take to protect yourself.

There were at least 166 identified cyber incidents in 2021 affecting 162 schools in 38 states, according to one report. Why haven’t our schools adopted better cybersecurity?

In their rush to install digital teaching tools, most districts haven’t carried out the more tedious task of installing robust cybersecurity systems and protocols. Few enforce basic cybersecurity hygiene such as two-factor authentication. In these information-rich environments, simple protocols can make a massive difference in protecting students’ personal information.

As for districts’ technology, several obstacles work against upgrades: budget cuts and limited funding, a lack of vision among school-district leaders and the need for approvals by school boards and union negotiations, according to an industry brief by Ultimate Kronos Group, a workforce management software vendor. When UKG experienced a massive hack in December that affected thousands of employers, it illustrated the extent of the risks K-12 districts face in relying on vendors.

Efforts are underway to protect schools’ data. This year President Biden signed into law the State and Local Cybersecurity Improvement Act, authorizing $1 billion in grants to state, local and tribal governmental entities — including school districts — to address cybersecurity threats and IT system risks. This step follows last year’s K-12 Cybersecurity Act tasking the Department of Homeland Security with reviewing cybersecurity threats to schools and issuing recommendations.

In addition to these funds and recommendations from the federal government, an incentive program might help — specifically via insurance policies. It’s difficult for any institution to qualify for cyber insurance without having sound security systems in place. The public education sector is considered a very high-risk industry for cyber insurance, according to Iram: “Security scans often reveal that the education sector has low resilience to cyber risk exposure.” And the premiums are high.

But it’s worth the investment to avoid or minimize debilitating business losses; many policies provide free or discounted pre-loss risk mitigation services and resources including legal counseling, PR specialists and IT forensics. The federal government can wield this tool by offering financial support for cybersecurity insurance — but only to those districts that align their systems with best practices.

The heavy toll of ransomware attacks on our schools’ finances, time and privacy makes clear that districts’ lack of preparedness is a recipe for disaster. It demands support from the government, tech industry and even the cybersecurity-insurance sector to fix.

Heidi Boghosian is an attorney and author of “‘I Have Nothing to Hide’ and 20 Other Myths About Surveillance and Privacy.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.