Human nature makes it easier to deny climate change than to confront it

- Share via

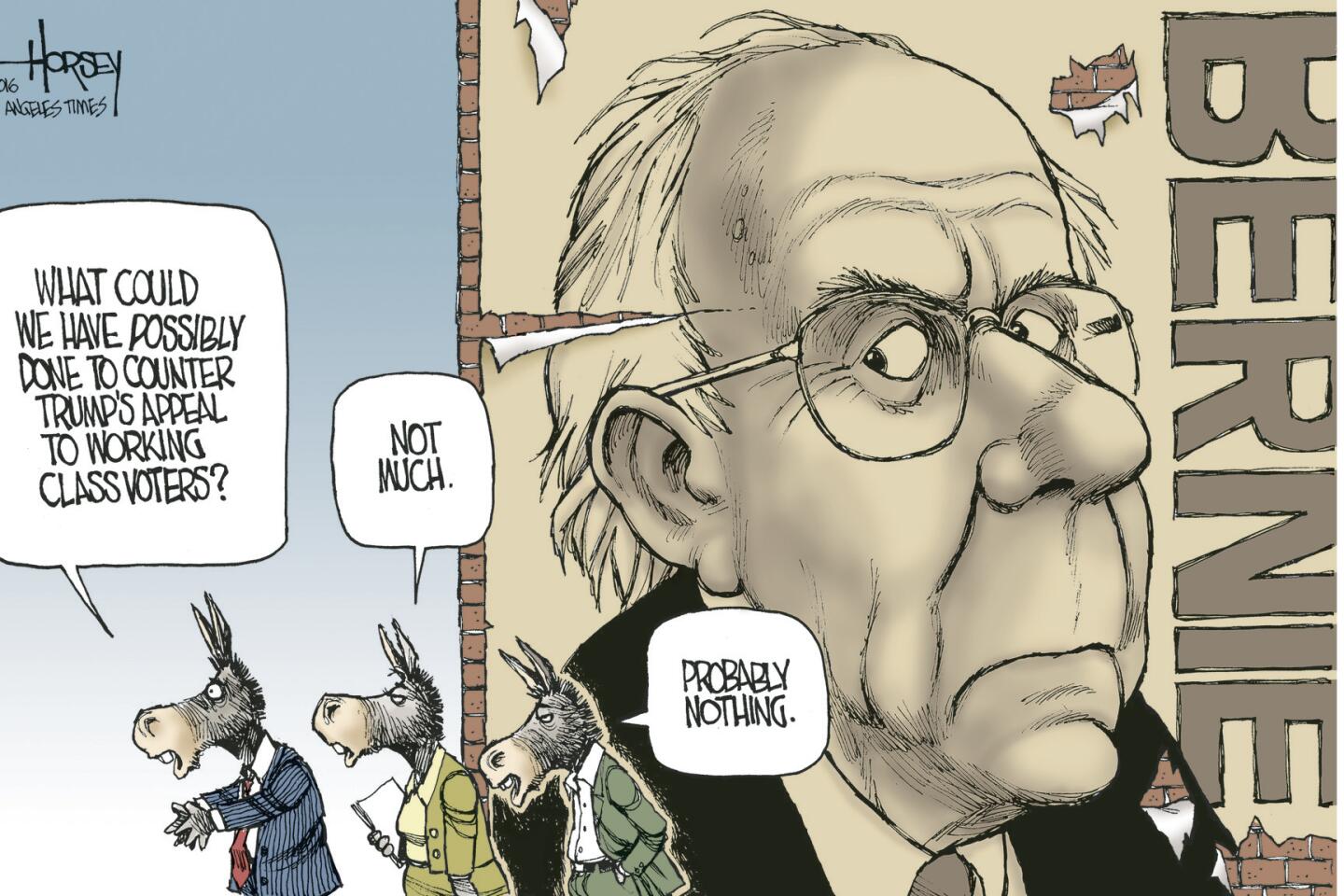

At one point in the Senate hearing to confirm Oklahoma Atty. Gen. Scott Pruitt as head of the Environmental Protection Agency, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders asked the nominee to share his personal views about climate change. Pruitt, a longtime ally of the oil industry and bane of the EPA, repeatedly evaded the question, saying policy and law, not his personal views, are what will be important as he carries out his duties.

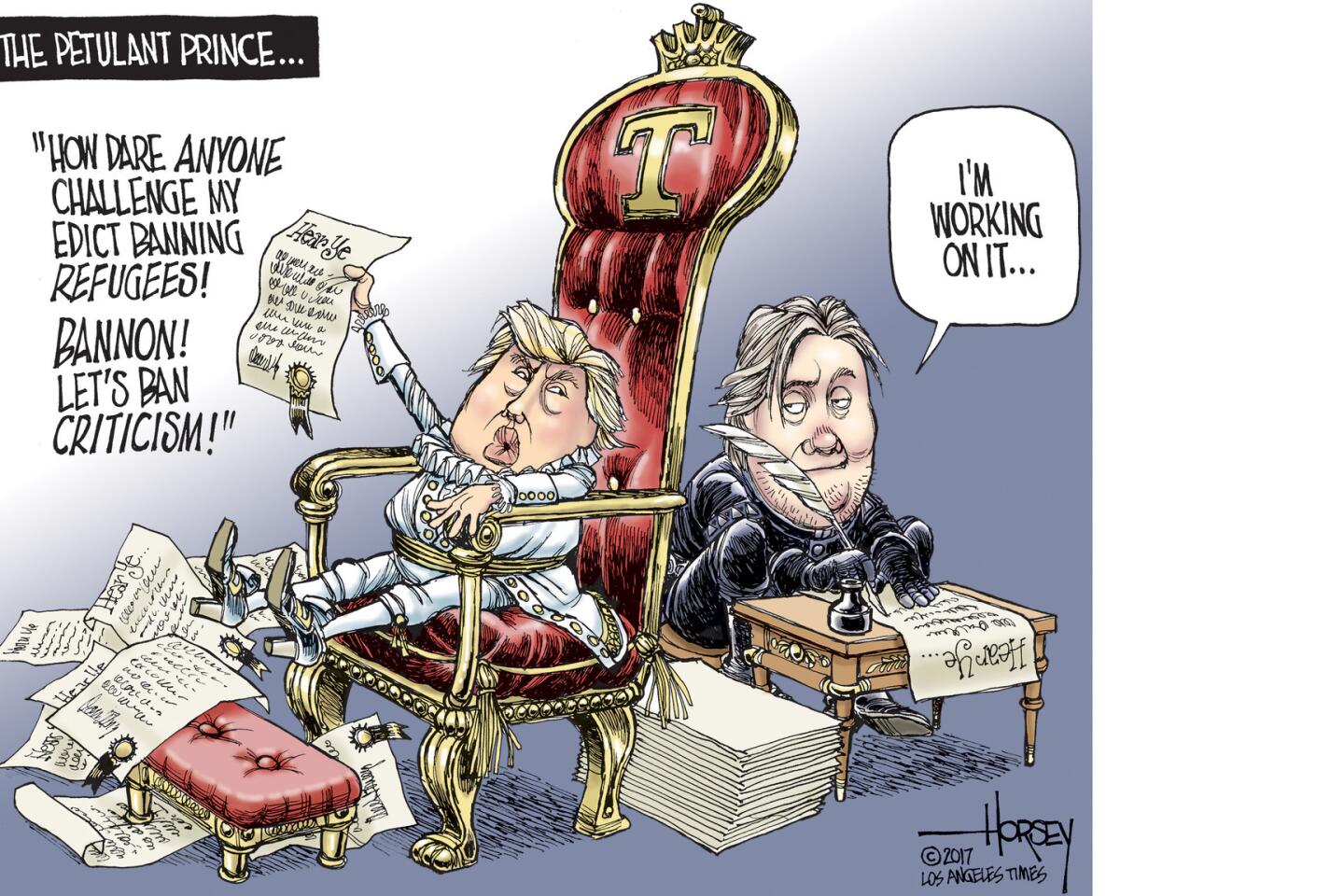

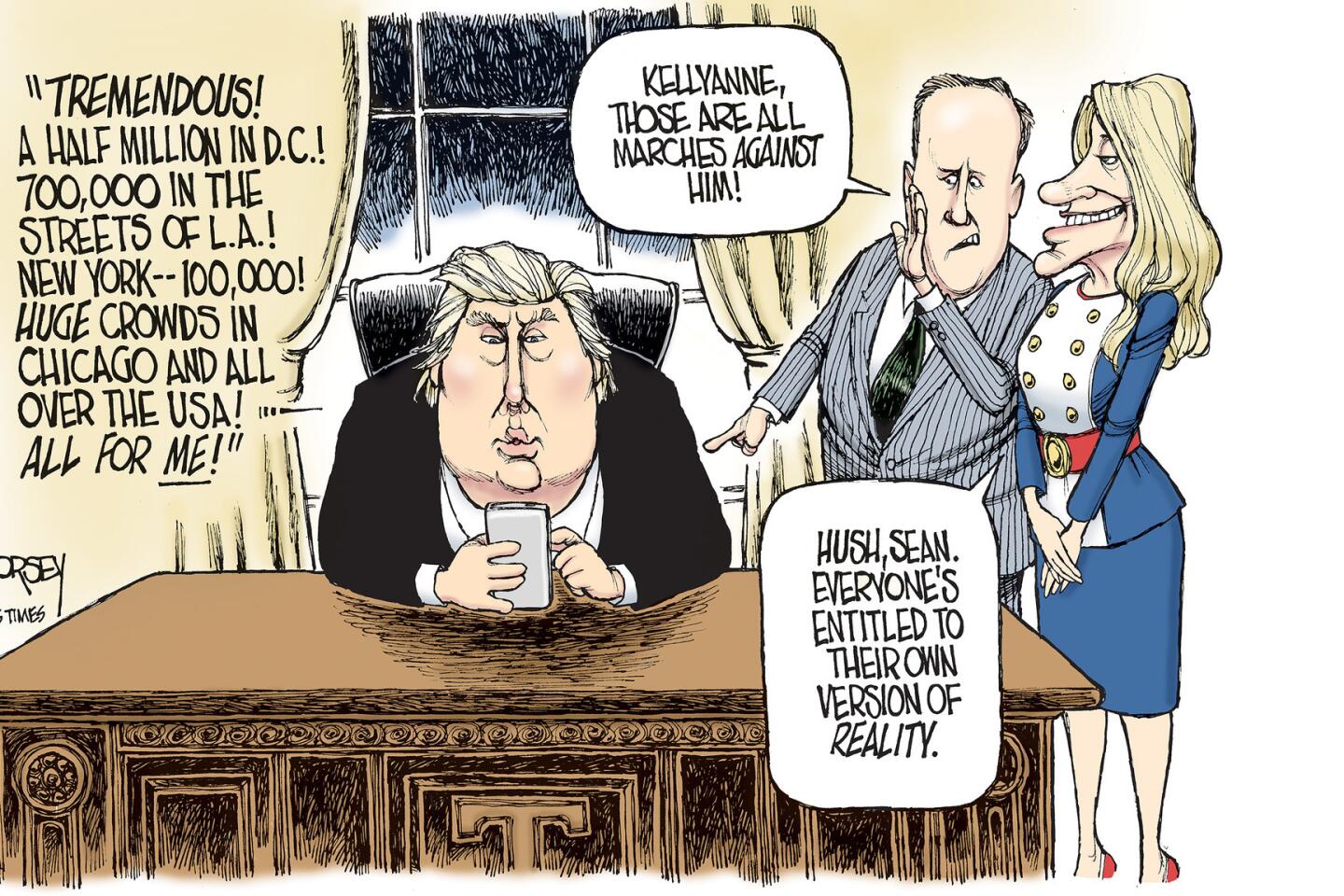

Sanders — and everyone who knows something about Pruitt’s record — scoffed at this. Pruitt is on record saying climate change science is “far from settled” and that climate “alarmists” should, perhaps, be prosecuted. But, really, Pruitt may be right. His personal views do not matter. What matters is what he does and, regarding that, there is no doubt.

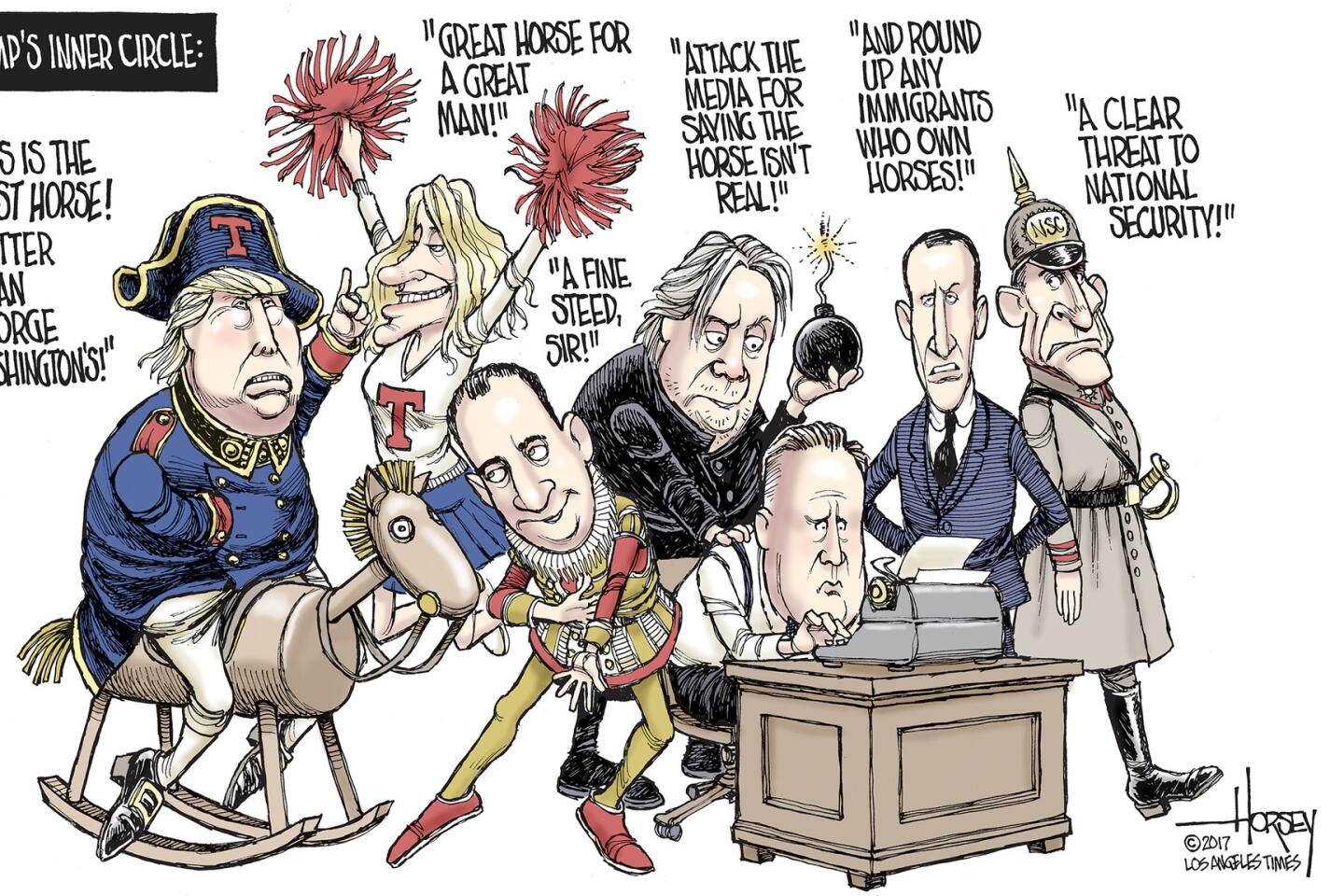

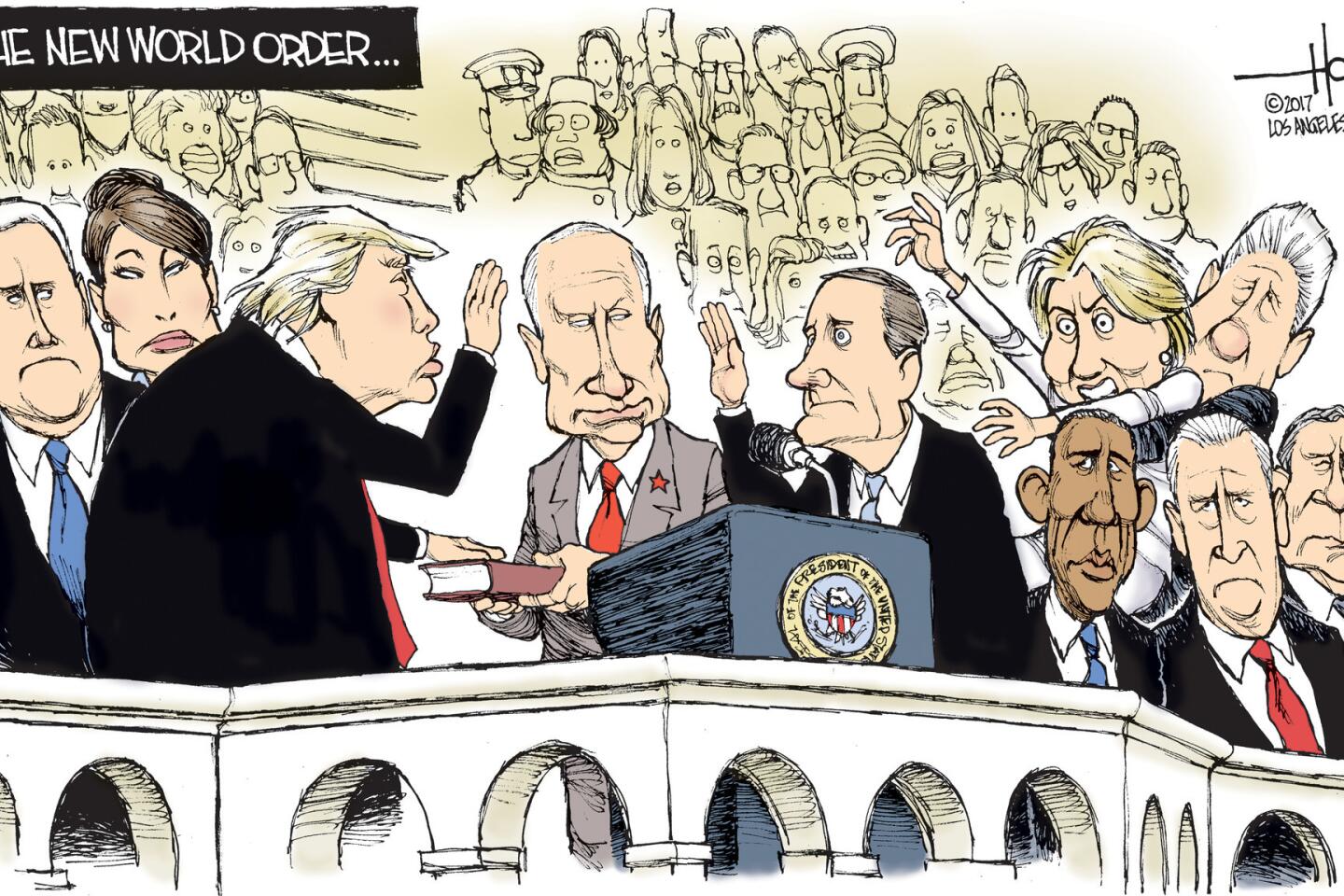

Pruitt, like many of his pals in the oil industry, may secretly accept that civilization is threatened with collapse if global temperatures continue to rise. He may know in his heart that human activities based on fossil fuels are the engine of the increase. He just doesn’t care. And neither does anyone else in the Trump administration.

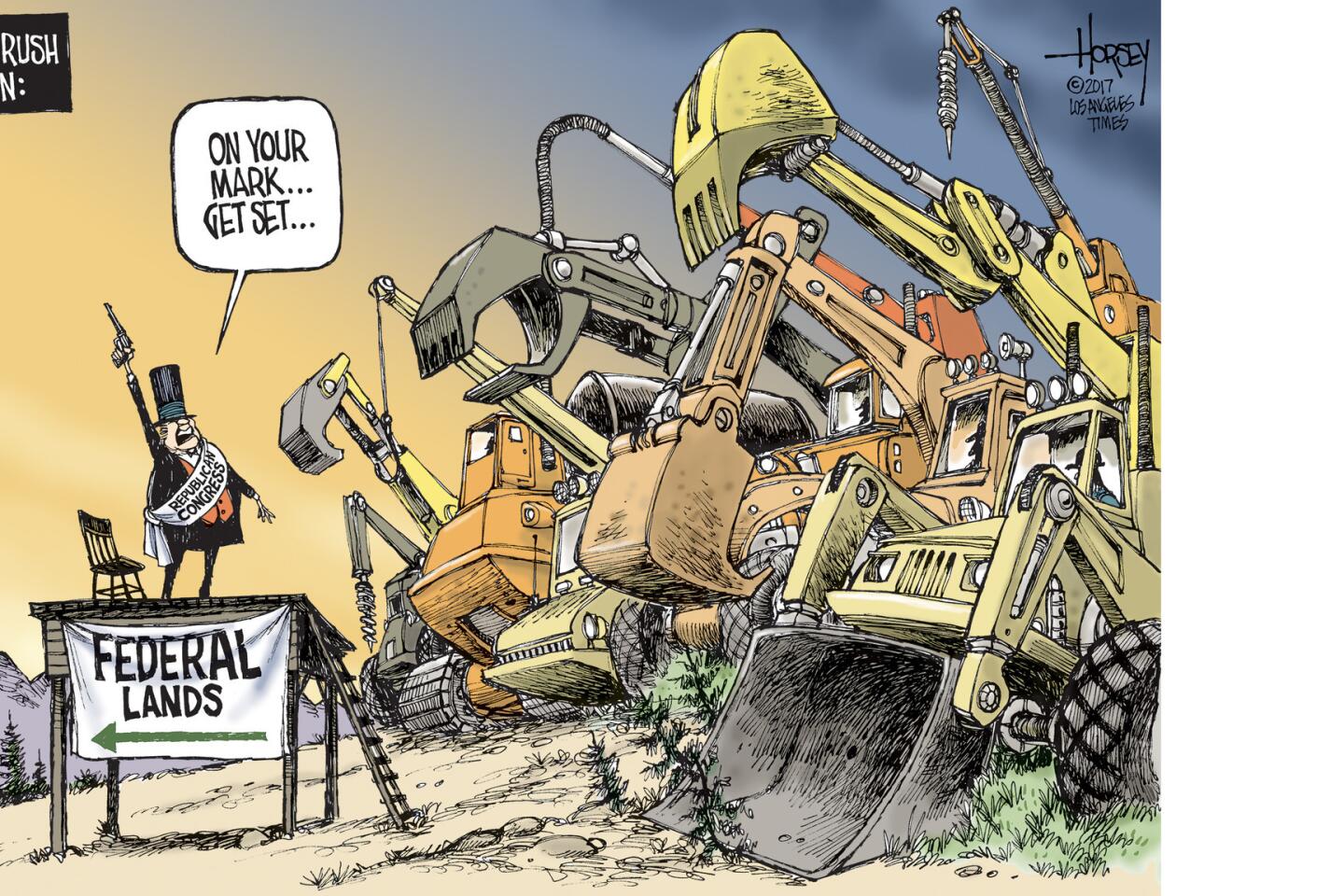

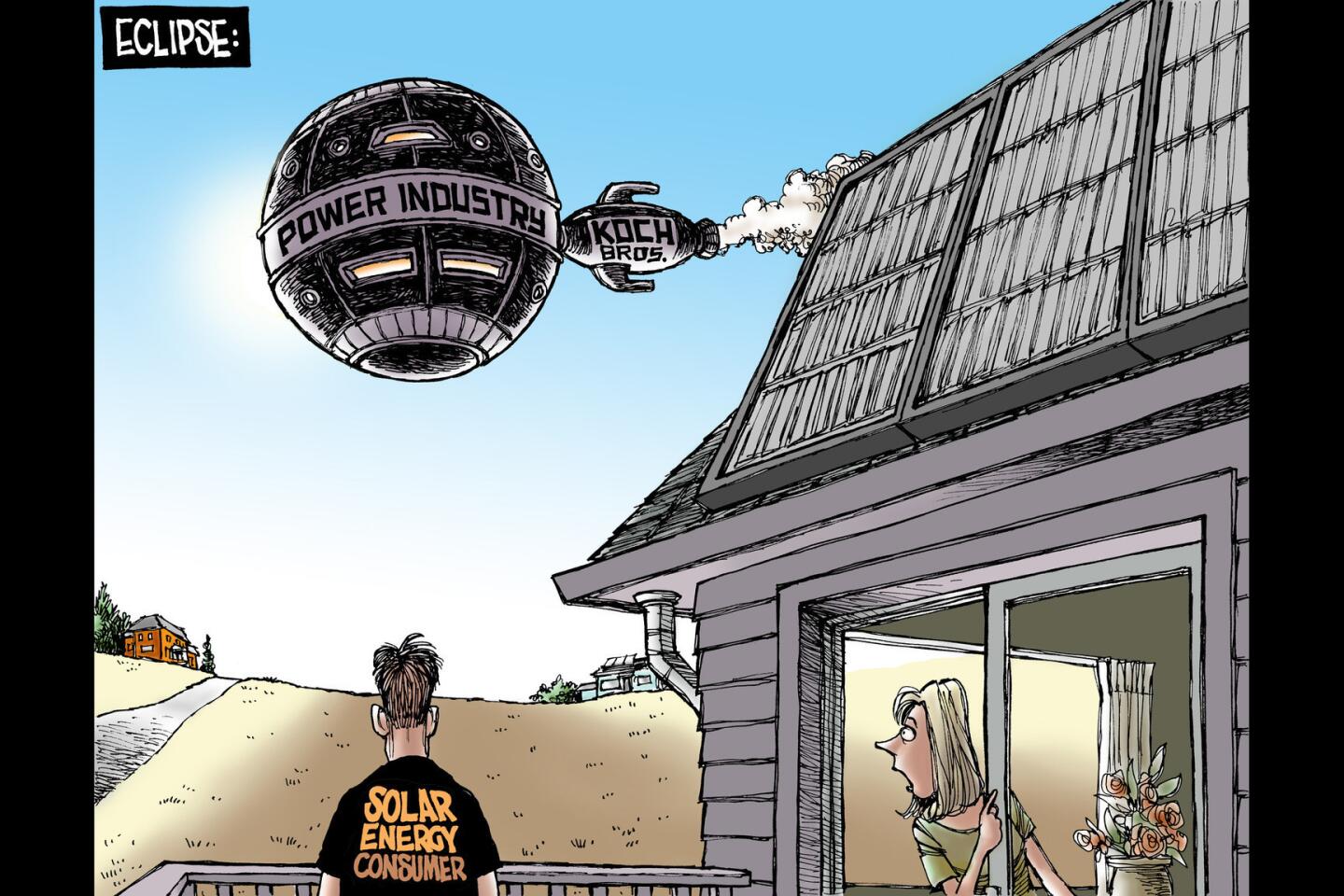

Frackers, miners, drillers, pipeline builders and refiners are going to be liberated from government restraints during the next four years because the new president and his appointees believe exploiting traditional American energy resources will bring jobs, profits and a booming economy. Stress over what may happen 50 or 100 years from now does not keep them awake at night. They care about immediate gains, not apocalyptic losses that will befall humanity after they are dead.

It is easy to condemn this selfish attitude, but it must be admitted that President Trump, Pruitt and their allies are not alone when they whistle cheerily as the graveyard comes into view.

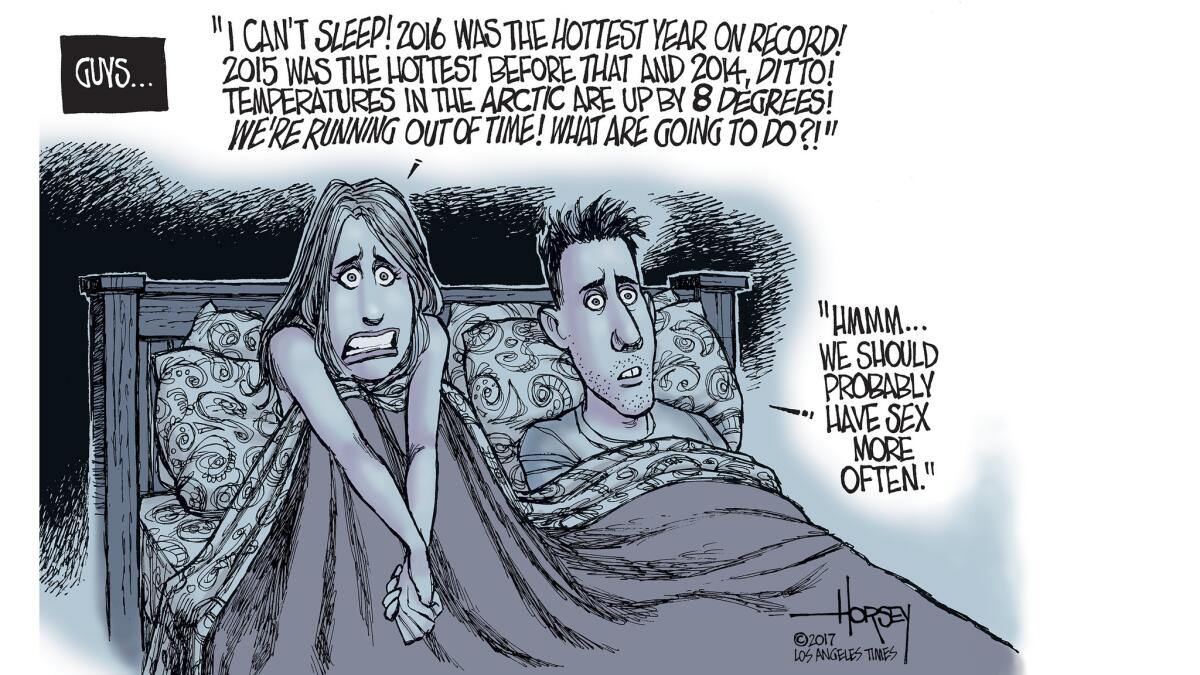

It may be that most human beings are psychologically incapable of confronting a danger that is monumental but just far enough distant that it can be ignored. It is a bit like death. All of us know death is inescapable, but we push back at thoughts of mortality and carry on as if we will live forever. Even in our dying days, we cling to optimistic fantasies that we might find a pill or procedure or a miracle that will give us a few more years. Personal obliteration is unimaginable — or maybe too imaginable — so we avoid thinking about it. We are deniers.

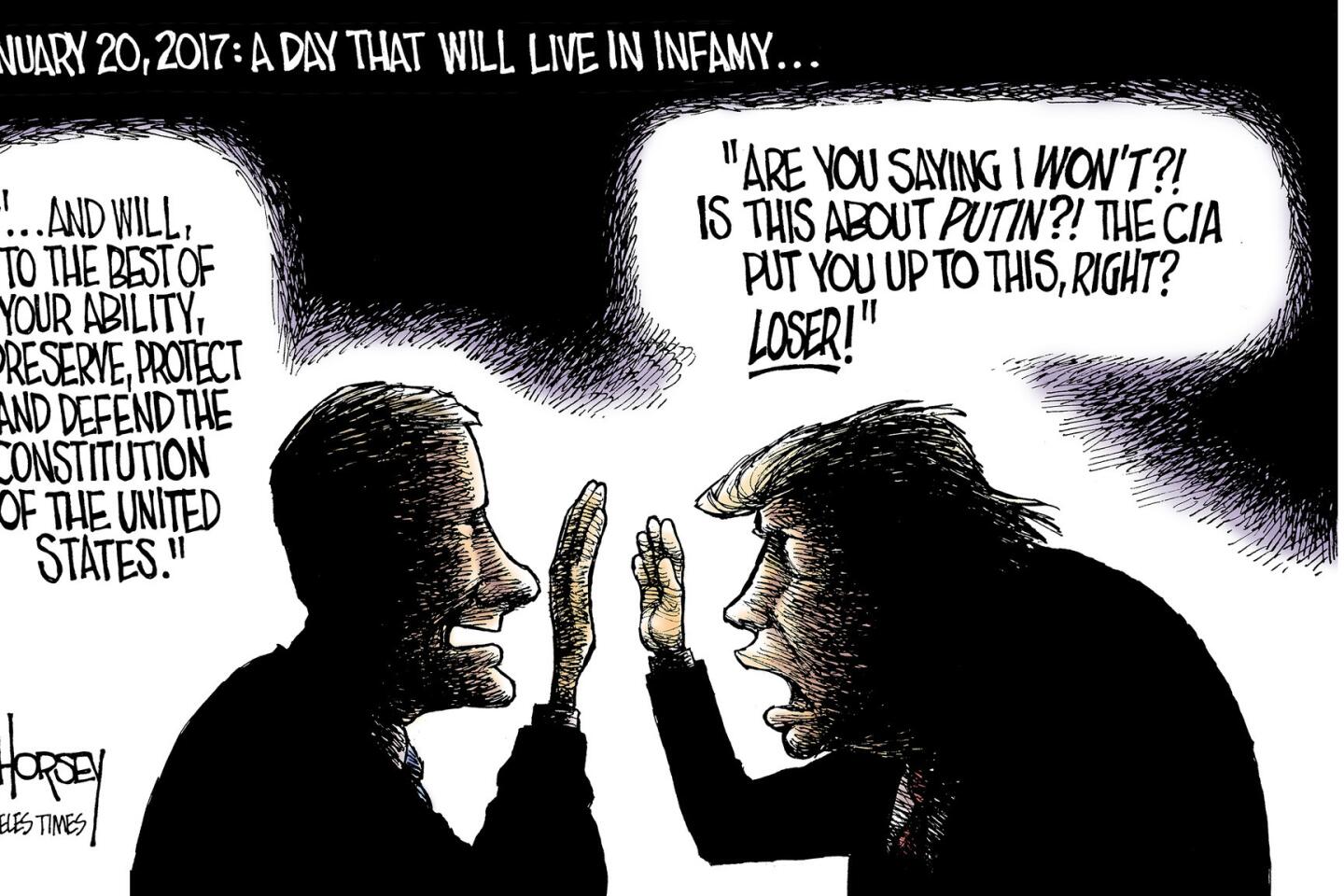

The world-altering effects of climate change are not as inevitable as death — at least not yet — but if one accepts the prevailing scientific consensus, we have precious little time to do the necessary things that might prevent its worst effects. A significant, hopeful step was taken by President Obama when he signed the Paris agreement, along with leaders of nearly 200 other countries, and pledged to take significant steps to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. Some environmental activists said the accord was not nearly enough, but it was a good start.

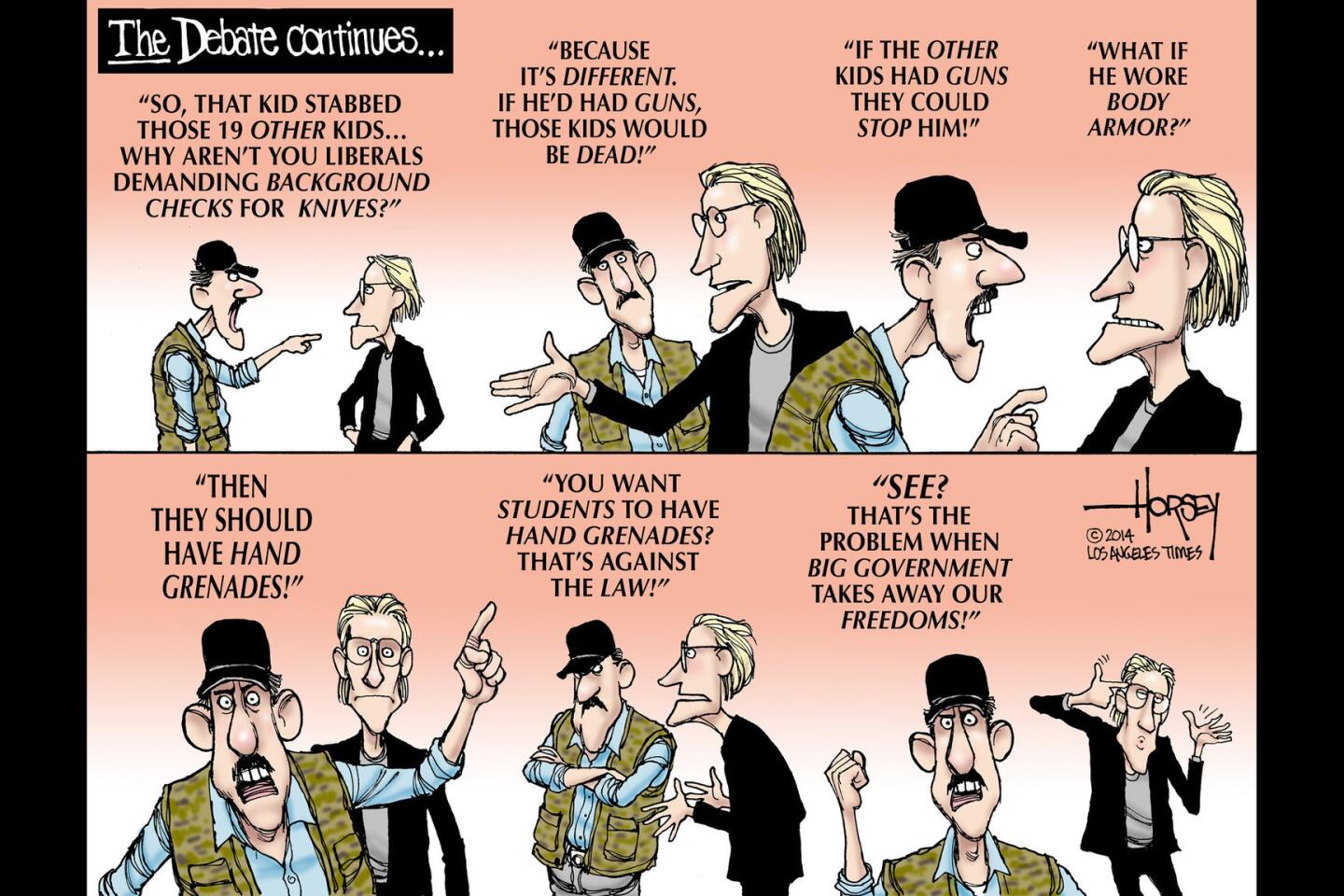

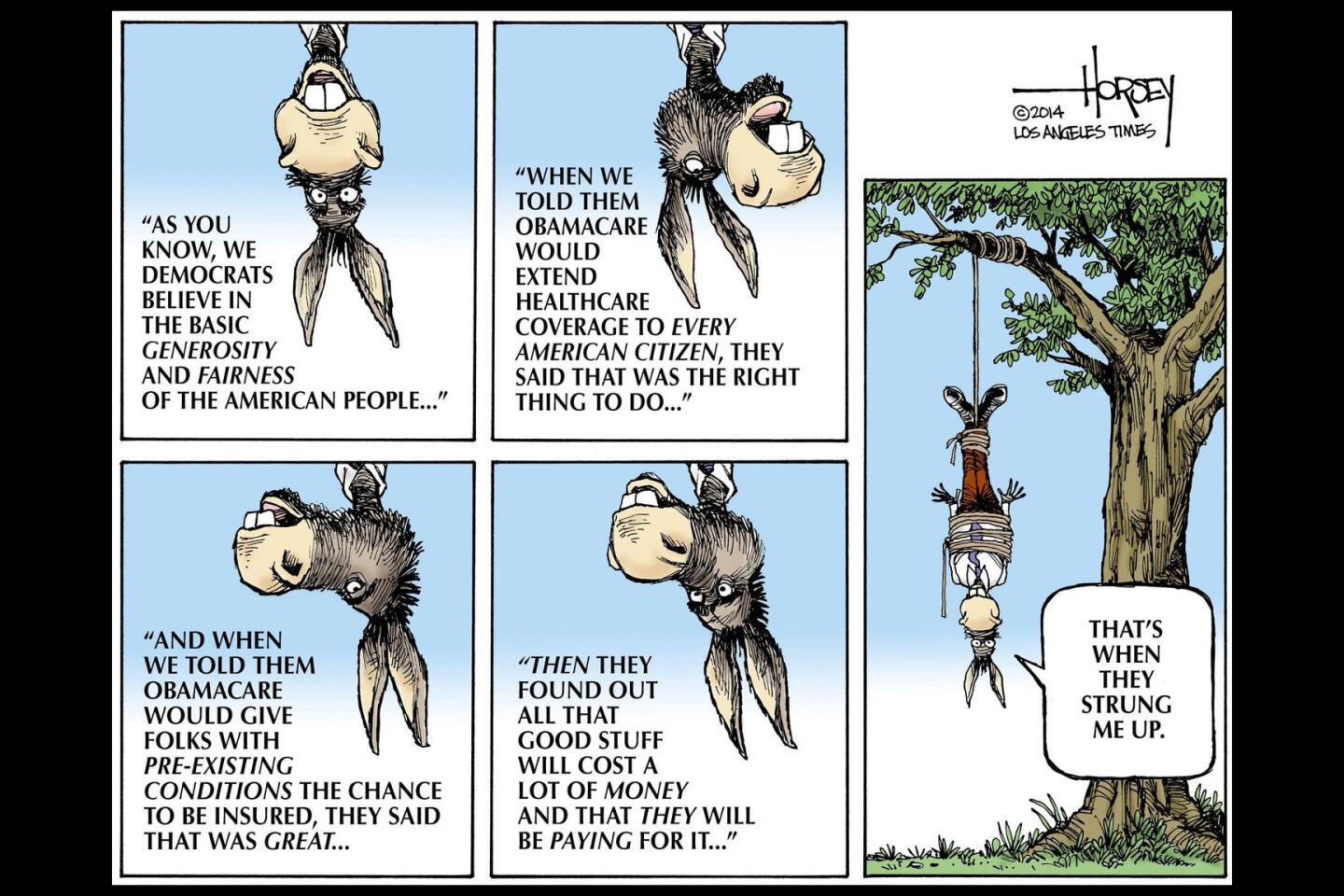

However limited the deal may be, does anyone think Trump will stick to the bargain? Snowballs have more chance in hell. Yet, I’m not sure his failure to act, as well as his unstinting support of the fossil fuels industry, will provoke the level of outrage that is justified. Democratic politicians will go to battle over healthcare. Thousands will turn out in the streets to protest police shootings or to support immigrants. Those are issues of immediate concern. But who will be there for the future of the planet?

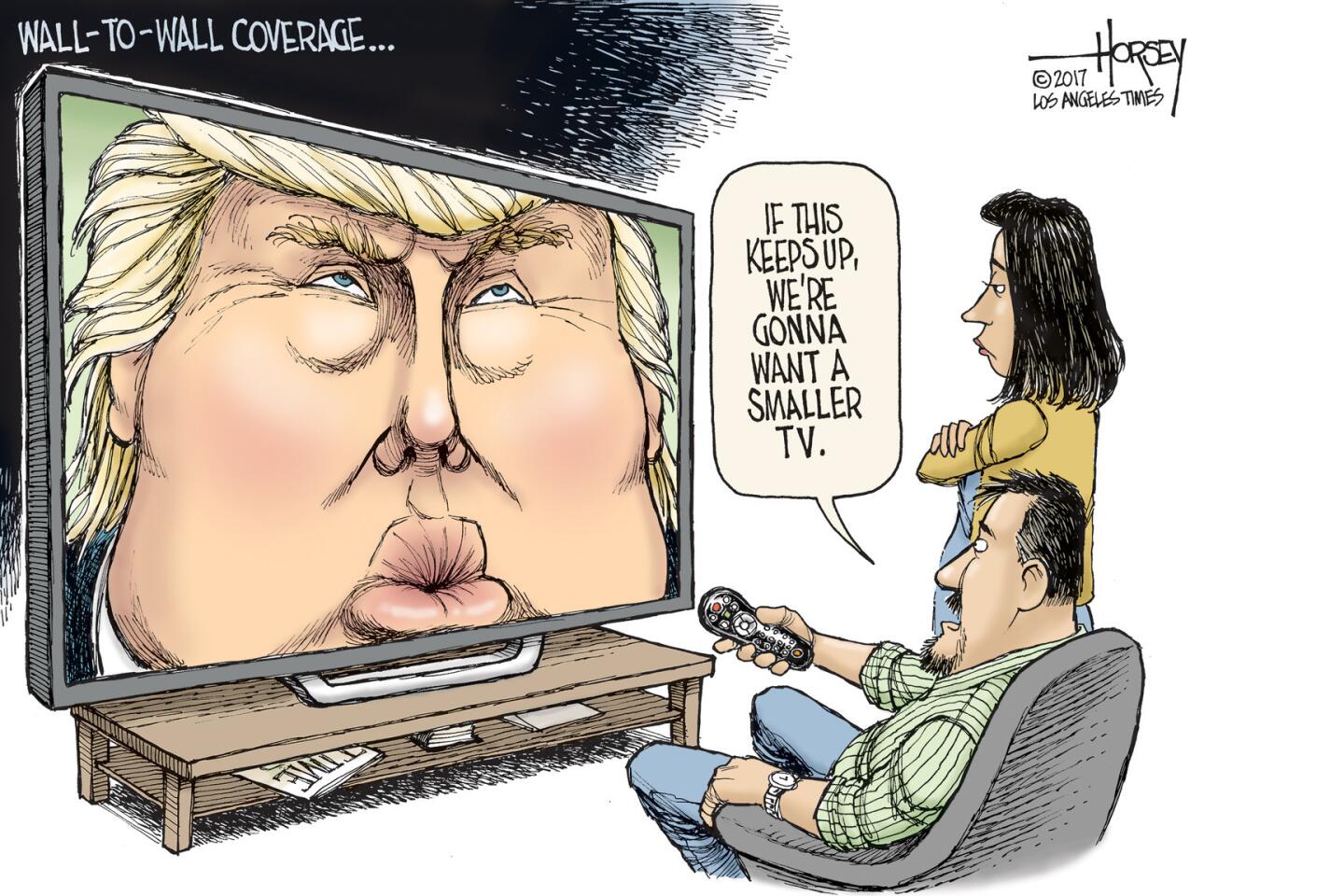

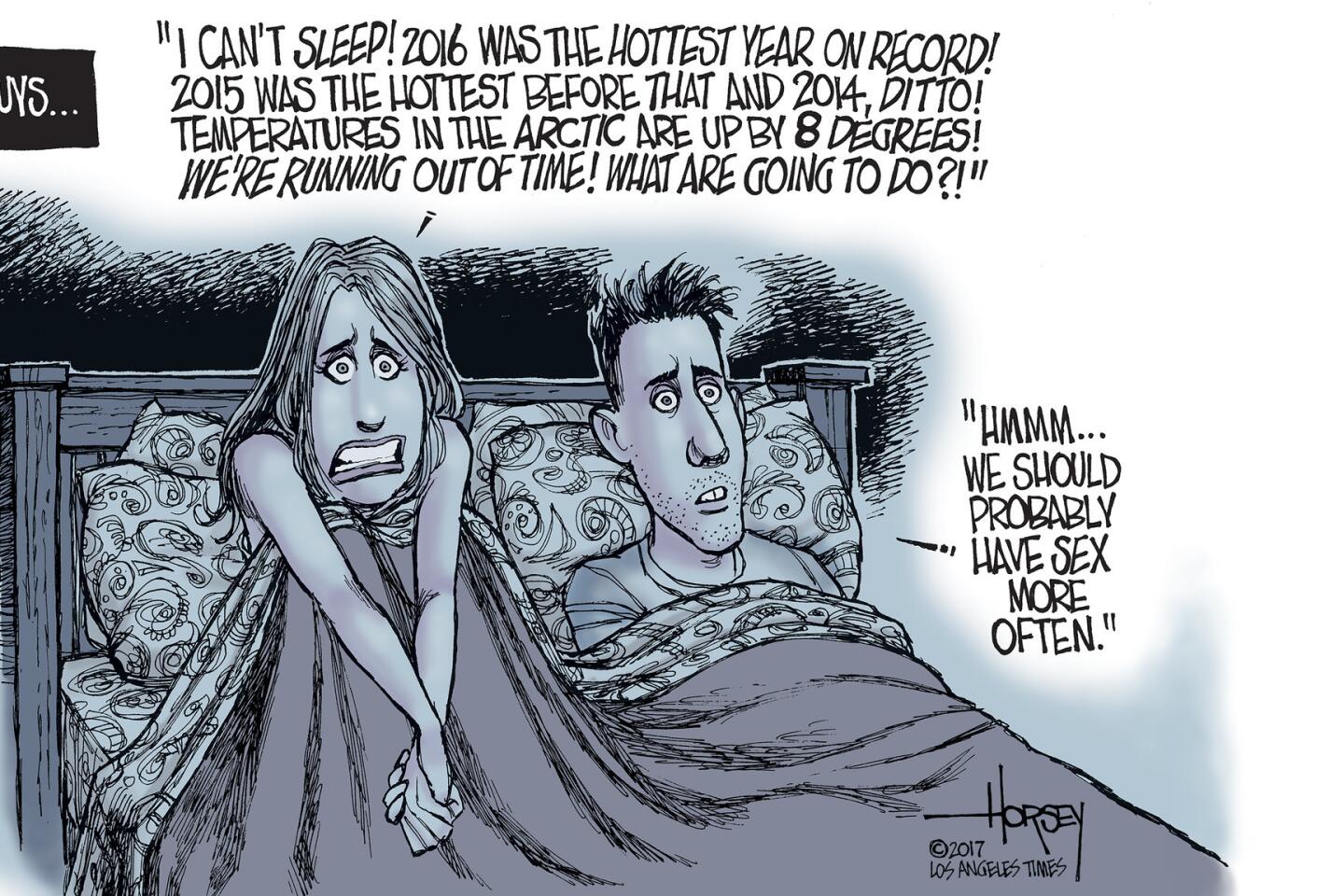

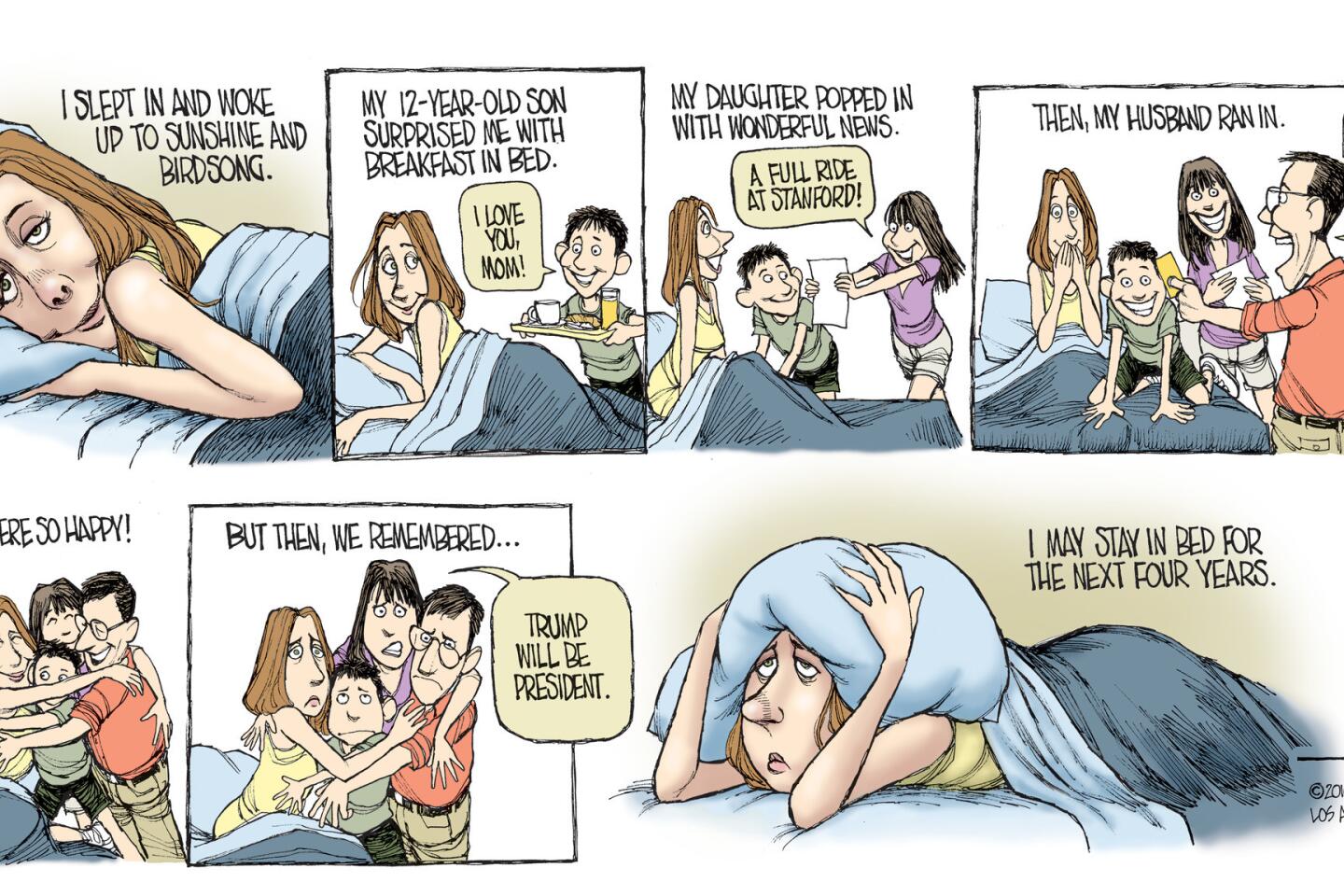

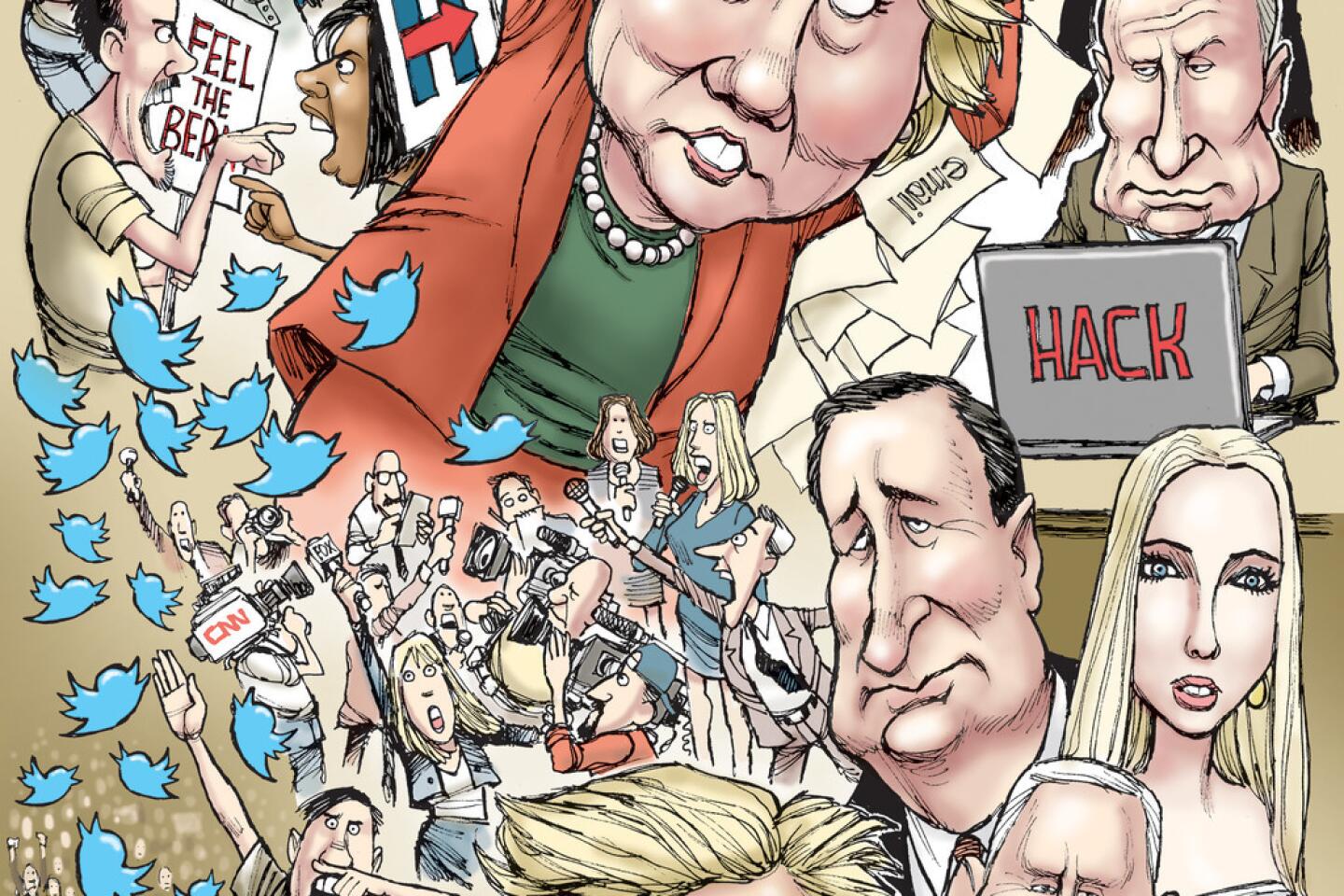

Putting climate change at the top of the political agenda where it belongs requires us to put it at the top of our consciousness. I am not sure we are willing to do that. Impending doom is a deeply disquieting companion. It is easier to concentrate on our child’s next soccer game or binge-watch some TV or think about sex or food or travel or be appalled by the president’s latest tweet.

Without leaders who show they understand the climate change threat and are committed to doing all they can to mitigate it, it feels hopeless. It is easier to avoid thinking about it, hope for a technological miracle that will fix it or, like Scott Pruitt, blithely deny it is there.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.