Biden’s abortion flip-flop shows how fast and far Democrats have shifted

- Share via

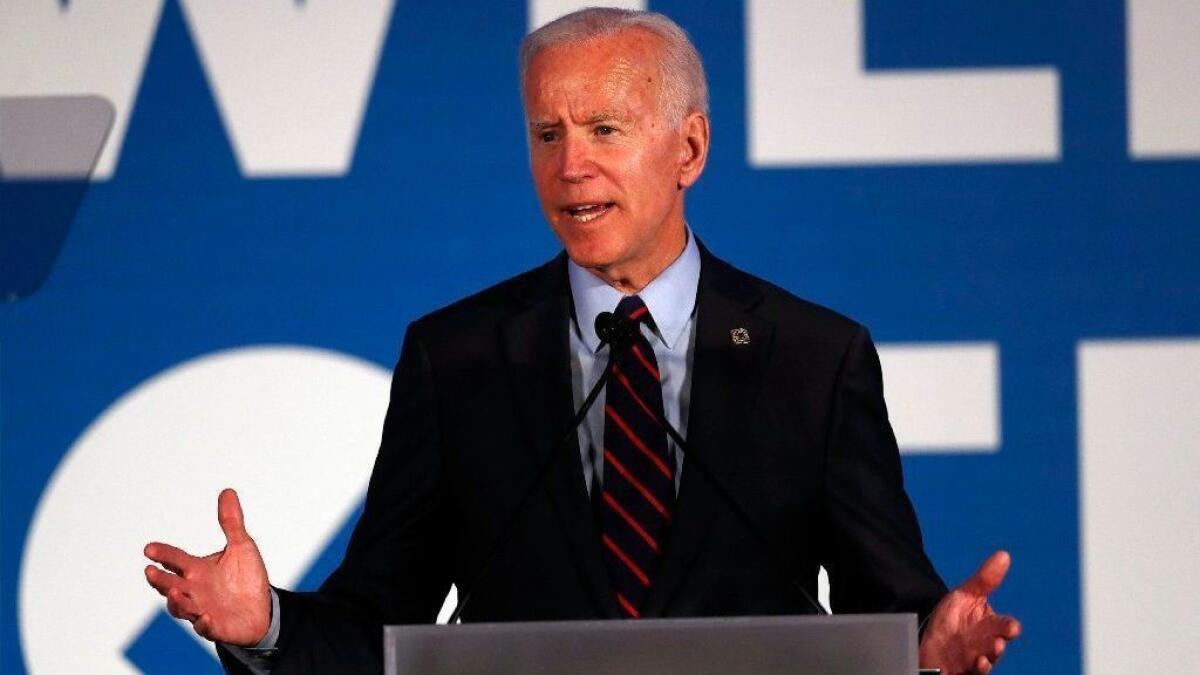

Reporting from Washington — Joe Biden’s announcement this week that he had reversed decades of opposition to using federal funds to pay for most abortions capped a rapid move within his party against what had been one of the few compromises in abortion politics.

On Wednesday, the Biden campaign said he still supported the longtime ban on using taxpayer funds to pay for abortions under Medicaid, a health program for low-income persons. After an outcry from other Democrats and abortion-rights supporters, he reversed course Thursday, bringing him in line with his party’s official policy.

Biden’s flip-flop, as inelegant as it may have been, illustrated how brisk the Democratic Party’s shift on the issue has been. The change also highlights the growing influence in the Democratic Party of women of color, who over the last decade led the movement to shift the party’s stand on abortion funding, as well as the widening gap between the two parties on abortion.

The Democrats essentially did a 180-degree turn on federal funding while Biden was serving as vice president and in the two years that he was out of office.

The last time Biden cast a vote in the Senate — 2008 — the ban on federal funds for abortion, known as the Hyde Amendment, was widely accepted by Republican and Democratic lawmakers, as well as mainstream abortion-rights groups.

By the time the Obama administration ended, by contrast, Democrats had adopted a call for repeal of the Hyde Amendment as part of their 2016 party platform.

“The conversation about abortion is just so different” today, said Destiny Lopez, co-director of the All* Above All Action Fund, a group that has advocated for ending the Hyde Amendment since 2013.

When the group started its advocacy, “the talking point was that Hyde was the law of the land — that was from so-called pro-choice folks,” she said. “You were able to be pro-choice and support the Hyde Amendment.”

Today, more than 150 Democratic lawmakers in the House and Senate — and with Biden’s switch, all the major 2020 presidential candidates — endorse ending the policy.

Biden has had to quickly catch up to where the Democratic base is today. Biden once voted to ban certain abortion procedures conducted late in pregnancy and was proud of his “middle of the road” position against the federal funding of abortion, as he wrote in his 2007 book, “Promises to Keep.”

“I take him at his word now that he has heard the will of the people,” Dr. Leana Wen, president and chief executive of Planned Parenthood, said Friday on C-SPAN’s “Newsmakers.”

Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Oakland), one of the most prominent advocates for repealing the Hyde restrictions, said she was in disbelief when she heard Biden supported the policy. She called his change of position proof of “democracy at work” but added a note of skepticism: “Given his inconsistencies in the past, I can’t read minds.”

The Hyde Amendment policy was crafted three years after the 1973 Roe vs. Wade Supreme Court decision, which legalized abortion nationwide. The restriction has been a part of federal spending laws ever since. While it was named for a longtime opponent of abortion, Rep. Henry Hyde of Illinois, the policy was viewed for years by both Republicans and Democrats as one of the few things the parties could agree on regarding abortion: The federal government wouldn’t pay for it.

Supporters of the ban, including some who were otherwise abortion-rights advocates, argued that in a society with a wide divergence of views on abortion, taxpayers should not be required to help pay for a procedure that many regard as immoral.

When the amendment passed, it was not controversial; abortion-rights supporters assumed the Supreme Court would knock the policy down. It didn’t.

For decades afterward, the Hyde Amendment stood as a compromise that neither party was eager to touch. The ban initially applied to Medicaid, but it has become a key point in debates over many other aspects of healthcare, including passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and even a small attempt to change the law last year.

Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times 2020 election calendar »

Since the late 1970s, abortion-rights advocates tried a few times to eliminate the ban. President Clinton briefly tried to do so, only to be turned down by Democrats in Congress.

Beginning in 2011 and 2012, however, organizations representing women of color began pushing to end the policy. They framed their message as a reproductive justice movement, arguing that the legality of abortion meant little if low-income women, many of them minorities, couldn’t access the procedure.

The Hyde Amendment “is discriminatory against people with low incomes and it also specifically discriminates and further silos out abortion care and treats it as different than any other aspect of healthcare,” said Wen.

Initially, mainstream abortion-rights groups, including Planned Parenthood, were reluctant to embrace the push to end the ban. But when Lee introduced a bill to end the policy in 2015, mainstream abortion-rights groups signed on.

Lee, who was a staffer on Capitol Hill when the Hyde Amendment was enacted, said she had tried for years to push back on the policy but didn’t have enough support from other lawmakers. She credited activists for pushing the issue and said GOP-led abortion restrictions had helped convince people that the time had come to end the restriction.

The calls to repeal the Hyde Amendment come as both sides of the abortion debate have largely given up trying to win over middle-of-the-road voters, reflecting a widening division in American politics on that and many other issues.

This year, several Republican-majority legislatures have moved to ban all abortions in their states, in some cases trying to prohibit the procedure as early as six weeks of pregnancy and without exceptions for pregnancies that result from rape or incest, an idea that was once considered too extreme to even think of and remains a step too far for many Republicans.

Last year, the last two House Republicans who broke ranks on abortion policy — Reps. Charlie Dent of Pennsylvania and Rodney Frelinghuysen of New Jersey — left office, with no similar replacements. On the Democratic side, abortion-rights groups have tried to oust one of the last antiabortion Democrats in the House, Rep. Dan Lipinski of Illinois.

While Democrats are coming to consensus on opposition to the Hyde Amendment, they aren’t ready to vote against omnibus bills that include the restriction. Nearly every sitting lawmaker has voted at least once for a bill including the Hyde restriction.

The prohibition on federal money for abortion is routinely attached to the annual bill that funds all government health programs, for example. If Democrats drew a firm line against it, they would put at risk billions of dollars in other programs, such as Title X family planning money.

“Opposing the Hyde Amendment in principle in 2020, especially in a Democratic primary, is logical,” said Mary Ziegler, a Florida State University law professor who has written extensively on the history of abortion politics.

“2020 would need to remake the landscape dramatically for this to be a realistic conversation. History shows it’s hard to get rid of the Hyde Amendment.”

More stories from Jennifer Haberkorn »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.