Supreme Court this year gave a preview of things to come: Wins for Trump, employers and Republicans

- Share via

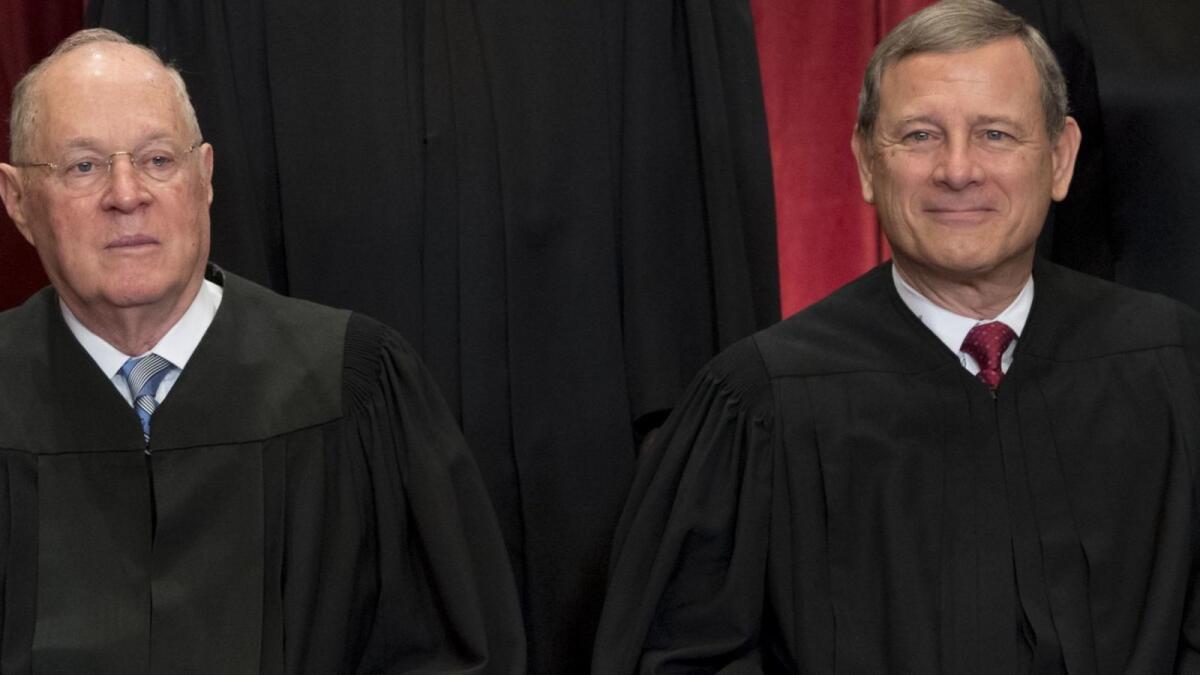

Reporting from Washington — The Supreme Court term that ended last week gave a preview of the new era ahead, when Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. may finally lead a solidly conservative majority — that doesn’t include an unpredictable justice sometimes willing to go his own way.

In the past two months, the justices strengthened President Trump’s power to enforce border controls, gave employers the power to block wage claims from groups of workers and refused to block partisan gerrymandering that helped Republicans keep control of Congress and many state legislatures.

They also upheld a Republican-led state’s drive to purge occasional voters from the rolls and effectively dealt a big budget cut to the public-sector unions that tend to support Democrats.

In nearly every key decision, the five Republican appointees were in the majority, while the four Democrats dissented.

One exception was in the area of privacy. Roberts has a libertarian streak, and he is concerned about the government’s power to amass huge amounts of data on nearly everyone. The chief justice spoke for the court in a major ruling on cellphone privacy. However, that was the only term-end decision that both liberals and conservatives could cheer.

This year, unlike in past terms, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, 81, did not hold down the middle position. Instead, he voted with the conservatives in every closely divided case, and then announced his retirement on the final day of the term. He cleared the way for Trump and the Republican-controlled Senate to replace him with a young and more reliable conservative.

Now Roberts has a clear path to pursue several long-standing goals of the conservative legal movement. They include ending race-based affirmative action in schools, colleges and possibly in employment.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Roberts wrote shortly after joining the court. He is likely now to have a majority to put his view into law. Two years ago, Kennedy joined the liberals to uphold a limited affirmative action plan at the University of Texas, with the chief justice in dissent.

Roberts also would move to make it far harder, and perhaps impossible, for civil rights lawyers to challenge election districts on the grounds they undercut the voting power of Latinos and African Americans. Last week, in a 5-4 decision, the court tossed out such a claim in a long-running Texas case.

On the other hand, religious liberty claims will get a new hearing. Kennedy was torn this year over the case of the Colorado baker who cited his Christian beliefs as grounds for refusing to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple (Masterpiece Cakeshop vs. Colorado). His opinion ended up skirting the broader issue and instead voicing support for both gay rights and religious freedom.

Last week, the justices sent back to Washington state judges a similar case involving a florist (Arlene’s Flowers vs. Washington). That dispute is likely to return to the high court in the year ahead. And with a fifth conservative vote, the religious liberty claim is almost sure to prevail.

The conservative legal movement grew in the 1980s under the Reagan administration, and prime target, then as now, was the right to abortion set in Roe vs. Wade. Roberts was a young lawyer in the Reagan White House and then served as deputy solicitor general under President George H.W. Bush. He was part of the legal team that sought a step-by-step overruling of the abortion right.

But that movement ended in a surprise defeat in the spring of 1992 when three Reagan-Bush appointees — Kennedy and Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and David H. Souter — joined an opinion upholding the abortion right as a matter of precedent. Conservatives, led by the late Justice Antonin Scalia and Justice Clarence Thomas, vowed that someday, that decision in Planned Parenthood vs. Casey would be overturned. As long as Kennedy stayed on the court, the fierce foes of abortion had no chance of succeeding. But in the years ahead, the chief justice likely will have with him four conservatives who can achieve their long-sought goal.

When presiding over a divided court, Roberts often has sought modest and narrow rulings. But for the most part, this has been more about tactics than principle. When Kennedy has been fully on board with the conservatives, the chief justice has moved boldly to change the law.

For example, Kennedy had broadly supported the notion that in politics, money is speech. And in the Citizens United case of 2010, Roberts assigned Kennedy an opinion that swept aside the post-World War II legal limits on independent campaign spending, including from corporations. The flow of big money has transformed races for the House and Senate, and helped Republicans hold an advantage.

Roberts has long voiced a disdain for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, though it retained near unanimous support in the House and Senate. Three years after opening the door for a surge in political spending with Citizens United, Roberts wrote a 5-4 ruling knocking out the key provision of the Voting Rights Act, freeing the Southern states from oversight.

The chief justice also has strongly opposed efforts to limit partisan gerrymandering. He has argued that drawing election maps is a political task that the Constitution left to politicians, not judges. Three years ago, he hoped to strike down the voter-approved measures in Arizona and California that put nonpartisan commissions in charge of drawing election districts, but Kennedy refused to provide the fifth vote (Arizona State Legislature vs. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission).

That option remains open for states, several of which have measures on the ballot this fall that would create nonpartisan bodies to draw the election districts.

This year, political reformers hoped the high court would take a stand against extreme partisan gerrymanders. In Wisconsin, a federal court had struck down a GOP map that assured Republicans would control 60% of the seats in the state House, even when Democrats won the most votes. But Roberts managed to scotch the case on procedural grounds (Gill vs. Whitford). Now, with Kennedy’s departure, there is little prospect that the court will stand in the way of politicians drawing skewed election districts to keep their party in power for a decade.

It made for an especially dispiriting year-end for the court’s liberals. Last week, they took turns reading impassioned dissents. “History will not look kindly on the court’s decision today,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in response to the upholding of the president’s travel ban. Justice Elena Kagan accused her colleagues of “weaponizing the 1st Amendment” to punish unions and to strike down disclosure laws like the California measure that had required faith-based pregnancy centers to notify patients whether they had licensed medical professionals.

Outside the court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, at age 85, is enjoying a late-in-life celebratory status that she finds rather astonishing. The movie, “RBG,” showing her indomitable spirit, has been a surprise box office hit. The daily scene at the court recently has been less encouraging.

Each day, after the rulings were announced and the gavel sounded, the assembled audience stands. Then there is a long, painful pause, lasting up to a minute, while Ginsburg rises from her seat and walks ever so slowly just a few steps, and disappears behind the thick red curtain.

More stories from David G. Savage »

Twitter: DavidGSavage

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.