Capitol Journal: Big changes are needed at UC — starting with the Kool-Aid-drinking Board of Regents

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Even the most devoted Old Blue, Bruin alumnus or Santa Cruz Banana Slug must be cringing at what the state auditor reported about University of California fiscal failures.

Veteran State Auditor Elaine Howle essentially found that UC has been poor-mouthing and demanding more tax dollars while secretly hoarding many millions, paying extravagant executive salaries and smacking students with higher tuitions.

She specifically targeted the office of UC President Janet Napolitano, the former U.S. Homeland Security chief and Arizona governor.

Some excerpts from the stinging 167-page report released Tuesday:

- Napolitano’s office “accumulated more than $175 million in restricted and discretionary reserves that it failed to disclose to the [UC Board of] Regents and created undisclosed budgets to spend those reserve funds.”

- “It received significantly more funds than it needed” over a four-year period, “and asked for increases in future funding based on its previous years’ over-estimated budgets rather than actual costs.”

- “Its budgets were inconsistent and misleading … making it difficult to compare budgets from year to year.”

- The UC president’s office “compensated its executives and administrative staff significantly more than their public sector counterparts” in state government and at the Cal State University system.

- Napolitano’s execs “intentionally interfered” with the audit by “inappropriately” forcing revision of campuses’ statements about the president’s office. The statements were initially critical, but were rewritten to make them positive.

Napolitano played it cool. Like the experienced politician she is, the UC president welcomed the “constructive input.” But she denied there was anywhere near $175 million hidden away. It was mostly all committed to various programs, she said.

The auditor, however, wrote that the UC president’s office “did not provide evidence that refuted our conclusion.”

Napolitano will get her chance next week when she’s scheduled to be grilled at a joint hearing of some legislative committees.

“I hope the University of California is not tone deaf,” says Assemblywoman Catharine Baker, a moderate Republican from Contra Costa County. She’s vice chairwoman of the Assembly Higher Education Committee.

“I’m deeply troubled by this very damning report. And I say that as an alumnus of the UC Berkeley law school. It’s very easy to pile on. We should give UC a chance to respond. And it better be good.”

Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Paramount), who sits on the UC Board of Regents, says, “We need really, really honest and straightforward answers.”

“A lot of things bother me” about the report, Rendon says, especially “charges that the UC president’s staff was obstructing the audit. That shows a tremendous need for more legislative oversight.”

UC can expect that in the future, the speaker adds, because legislators now are taking a longer view of things because of revised term limits. A 2012 ballot measure lengthened a legislator’s allowable time in the Assembly from six to 12 years, and in the Senate from eight to 12. That will result in more audits and oversight, Rendon predicts.

UC is one of California’s oldest and most revered institutions, with 10 campuses and about 252,000 students, including 199,000 undergrads. It is inarguably world-class.

But in recent years, particularly during budget brawls and UC bureaucracy bloating, it has seemed, for many, to become arrogant and a bit self-worshiping. It’s pretty insular. And governing regents seem to drink the UC Kool-Aid rather than perform as a public watchdog.

The university is autonomous, so the Legislature’s power over it is limited. Maybe that’s good. It keeps the politicians at arm’s length. But perhaps the institution is too independent.

The auditor recommended some tightening up, such as legislative approval of the UC president’s office budget. That would be fiercely fought by UC.

Tensions have grown in recent decades as tuition soared and UC turned to out-of-state students for extra funds. They pay a much higher fare than resident students, but also take up slots that Californians want.

The regents angered many again recently by approving a 2.5% hike in tuition, raising it to $11,502 annually, plus $1,128 in separate student fees.

“It is outrageous and unjust to force tuition hikes on students while UC hides secret funds,” asserted Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, a regent and leading candidate for governor in next year’s election. He urged the regents to scrub the tuition boost.

A problem for UC, however, is that state government has cut back on its share of funding for the university since the glory days of low tuition. For many generations, there was no tuition at all.

But Proposition 13, the 1978 property tax-cutting initiative, led the state to spend much more money on K-12 schools and local governments, leaving less for the universities. Also blame escalating costs for healthcare and prisons.

The state now provides $3.6 billion of UC’s total $32-billion funding.

“We do need to fund UC and CSU at a higher level,” Rendon says. “But the UC Office of the President shouldn’t be hiding money. And it doesn’t excuse the president’s staff for being obstructionist.”

It all may be coming to a head. There have been eight state audits of UC in four years, showing legislative angst.

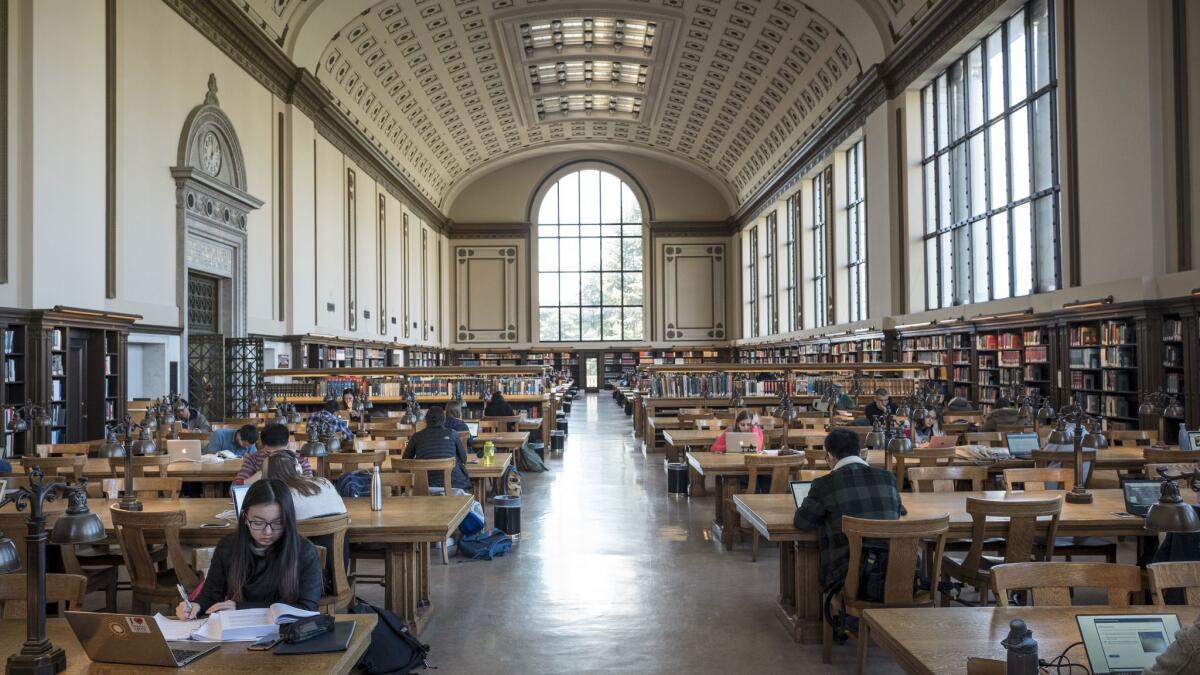

“The whole state wants to make college more accessible,” says Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento), chairman of the budget subcommittee on education finance, who requested the audit. “That’s why it drives people crazy that hundreds of millions of dollars may be hidden in an ivory tower in Oakland.”

UC needs to rethink and revamp, starting with the puppy dog regents.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

ALSO

It’s time for California to stop leaning on the rich and take up state tax reform

Was Gov. Brown wrong to make side deals to push through the gas tax hike? No, that’s democracy

Should California move up its primary to become a bigger player in deciding presidential elections?

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.