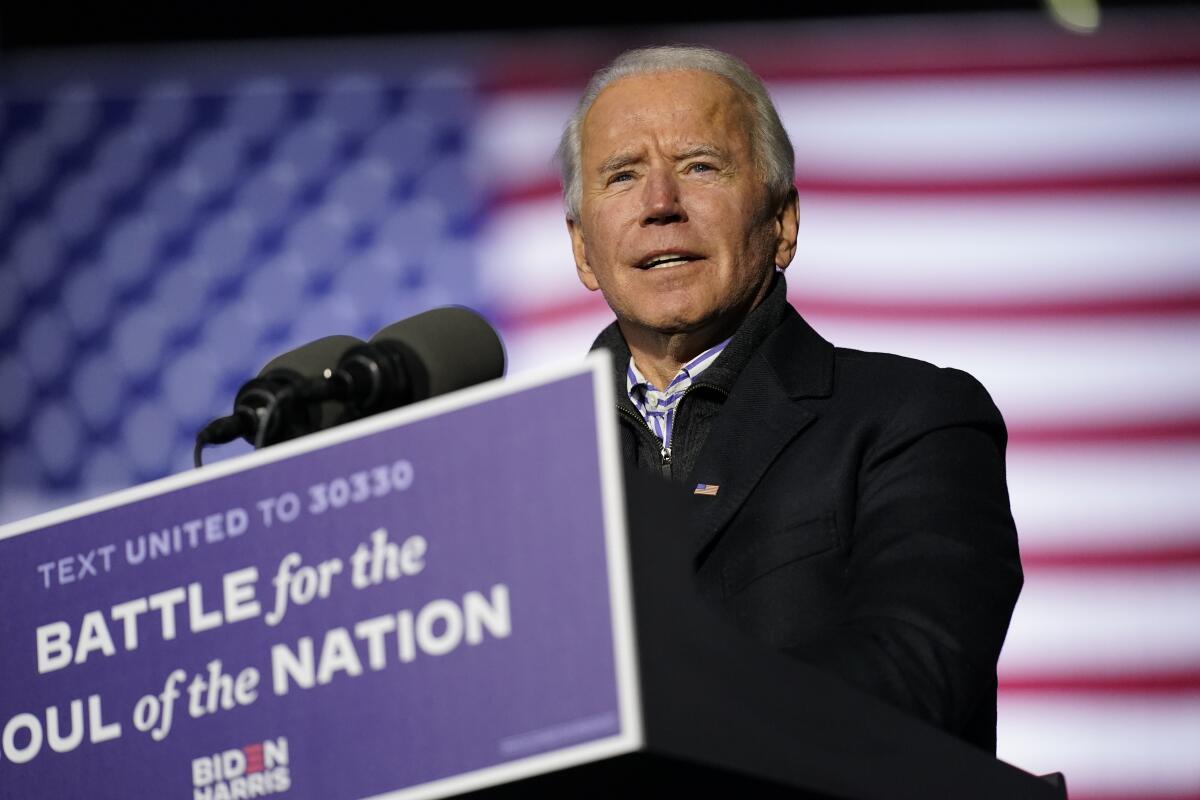

Essential Politics: Biden changes the political map

- Share via

WASHINGTON — For a decade or more, Democratic strategists have said their party stood on the verge of broadening their political map: Georgia and Arizona would eventually become competitive states, they insisted.

That belief suffered repeated setbacks. Democrats lost when Jason Carter, the grandson of the former president, failed in his race for Georgia’s governorship in 2014. They fell just short, again, when Stacey Abrams lost her bid for the governorship four years later.

Similarly, in Arizona, Democrats lost repeatedly statewide, although they scored some major victories at local levels, including the defeat of Joe Arpaio, the notoriously anti-immigrant sheriff of Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In both states, Joe Biden currently leads the presidential race by a narrow margin. If those leads stand, they’ll be significant triumphs for the party, giving Biden 306 electoral votes — the same number that President Trump won four years ago and hailed as a landslide. But Biden will be able to claim, in addition, a significant victory in the popular vote, which he is on track to win by at least four or five percentage points.

At minimum, Biden’s standing shows that the long-anticipated shift to competitive status in the Sunbelt has now arrived, brought on by demographic change, relentless organizing efforts and Trump’s polarizing impact.

Sunbelt breakthrough

With Mark Kelly‘s election, Arizona will now have two Democratic senators for the first time since Republican Barry Goldwater won in 1952. And in Georgia, both of the state’s Senate seats seem headed for runoffs on Jan. 5 — races that likely will determine which party holds the Senate majority.

That’s a big shift from Tuesday night, when Democratic losses in Florida and Texas set the tone for coverage.

That doesn’t mean Democrats got the “blue wave” they had been hoping for.

The party lost at least a half-dozen congressional seats and failed to flip state legislative chambers in Texas, North Carolina and other places where gerrymanders have bolstered Republican power. That means Republicans will still be in position to dominate the drawing of district boundaries in those states after the current census.

Moreover, even as Democrats made gains in parts of the Sunbelt, Republicans reinforced their hold on Florida, largely on the strength of their appeal to Latino voters in the Miami area.

Democrats also fell well short of their goals in Texas, where they had hoped to pick up several House seats. Some of those defeats were caused by the Democrats’ failure to engage Texas’ Latino population, which is large but prone to low turnout in elections. But the party’s candidates also lost races in the Dallas and Houston suburbs where they had hoped to build on the gains they made among white voters in the 2018 midterms.

Nevertheless, the gains that Biden did make — eroding Trump’s margins in working-class areas like northeastern Pennsylvania and Macomb County, outside Detroit; inspiring larger turnout of Black voters in Philadelphia, metro Atlanta and other major cities; and bolstering his party’s support in suburban areas from Charlotte, N.C., to Milwaukee to Phoenix — created a strong coalition that his party can now hope to build on.

Whether the Democrats will be able to follow through on that will depend on major blocs of voters that will be up for grabs over the next two years. The first tests will come with those Senate runoff races in Georgia, which will feature Republican Sen. David Perdue against Democrat Jon Ossoff in a regular election for a six-year term, and Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler against Rev. Raphael Warnock in a special election to fill the remaining two years of the term of retired Sen. Johnny Isaakson.

Of top concern for both parties: What happens with those suburban voters who voted for Democrats in 2018 and 2020 because of their revulsion to Trump?

Many are former Republicans or moderately conservative independents. Have Democrats converted them, or just rented them for a couple of elections? If the former proves true, the party can hope for further consolidation of its majority. But if it’s the latter, Republicans could be in position to retake the House in two years, since the party out of power typically makes gains in the first midterm election of a new presidency.

Keeping the loyalty of suburban voters while still motivating the party’s more liberal core will pose a significant challenge to Biden and Democratic congressional strategists. Already this week, the party’s ideological strains were on public display as centrist lawmakers, like Rep. Abigail Spanberger of Virginia, lashed out at progressives for having pushed issues such as “defund the police” that she said had endangered her reelection and caused the party’s losses in more conservative districts.

Republicans face their own divisions. On Thursday, Trump’s eldest son, Donald Jr., attacked the party’s 2024 presidential hopefuls for not coming to his father’s defense. More broadly, the party hasn’t yet figured out whether it can harness the fervor of Trump’s supporters without the appeals to racism and anti-immigrant sentiment that caused the suburban backlash.

The two parties face a similar conundrum with the other big voter bloc that 2020 proved was at play — Latinos.

Republicans clearly succeeded in appealing to Cuban American and other Latin American communities in Florida. That’s not just a Trump phenomenon. Support from those voters played a major role in the 2018 victories of Gov. Ron DeSantis and Sen. Rick Scott.

The most optimistic Republicans believe they can build on their successes so far and form a multiracial party that would combine socially conservative Latino voters with blue-collar whites under the banner of a center-right populism, embracing the more politically attractive parts of Trumpism without the president’s personal baggage.

Whether that’s feasible — or whether racial tensions would inevitably tear any such coalition apart — will be a major question for the next several years.

On the other side, Democrats can point to Arizona as evidence that mobilizing Latino voters can be key to victory for them in the Southwest. But their failures in Texas showed the limits of their strategy so far.

Within the party, a debate is already raging about the extent to which this year’s emphasis on racial justice issues helped mobilize key constituencies versus turning off voters

who really wanted to hear more about healthcare, the minimum wage and other pocketbook concerns.

Those tensions within each party will shape the policies and legislative battles of a Biden administration. For now, however, as he prepares to take on the title president-elect, Biden can savor the moment of a victory that was hard won, but, in the end, convincing.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest on the election

We’ve been covering all the twists and turns since the vote counting began on Tuesday. Here are some highlights:

— The election demonstrated the lasting strength of the nation’s partisan divisions, even amid massive turnout, as Janet Hook and I wrote in our next-day analysis.

— And the polls underestimated Trump again, but not by as much as you might think. I looked at the reasons why.

— The long count also jangled nerves of voters on both sides, as a team of Los Angeles Times reporters found around the country. Heightening tensions were protests in several cities, including some outside of vote-counting centers, as Tyrone Beason, Michael Finnegan and Matt Pearce wrote.

— Even on Tuesday night, Trump began launching a legal barrage to try to slow Biden’s progress, as Chris Megerian, Eli Stokols and Noah Bierman reported. The president’s claims brought condemnation and derision from legal experts, as Melissa Gomez reported.

— As Bierman and Megerian wrote, Trump and his allies sent conflicting messages: Stop the count in some states, finish in others. But his claims grew darker and more bizarre as the likelihood of loss set in, as Megerian and Stokols wrote.

— Moreover, as David Savage wrote, Trump now faces the same problem that then-Vice President Al Gore faced in 2000: It’s not easy to persuade judges to overturn an election once the votes have been counted.

— Some states may go to recounts. Matt Pearce wrote about the rules for that.

— As Maya Lau and Laura Nelson reported, one of the most important legal proceedings involved a federal judge lambasting the U.S. Postal Service for not following his orders to find and deliver mail-in ballots.

— Britny Mejia looked at the Democrats’ failures to fully engage Latino voters.

— Sarah Wire examined the Democrats’ losses in the House.

The latest from California

In Los Angeles, the local elections signaled a major progressive victory, Dakota Smith and Julia Wick wrote.

Both in L.A. and statewide, voters took big steps toward criminal justice reform. Among the biggest victories, progressive George Gascón will take control of the nation’s largest local prosecutor’s office after incumbent Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey conceded today.

But in Orange County, Republicans may be able to take back two seats in the House that they lost to Democrats in 2018.

Statewide, voters sided with Uber, Lyft and other app platforms in their hugely expensive battle with labor unions over worker protections. The president of Lyft says he’d still like to negotiate a compromise with unions, Taryn Luna reported. Voters also rejected a proposal to revive affirmative action, killed a proposal for rent control, and rejected a measure that would have allowed 17-year-olds to vote.

The results on the ballot propositions showed that an initiative process that was originally designed as a way for voters to get around the power of vested interests has now often become a tool for rich and powerful corporations, John Myers wrote.

Stay in touch

Send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com. If you like this newsletter, tell your friends to sign up.

Until next time, keep track of all the developments in national politics and the Trump administration on our Politics page and on Twitter at @latimespolitics.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.