Essential Politics: A Californian view of Democratic division

- Share via

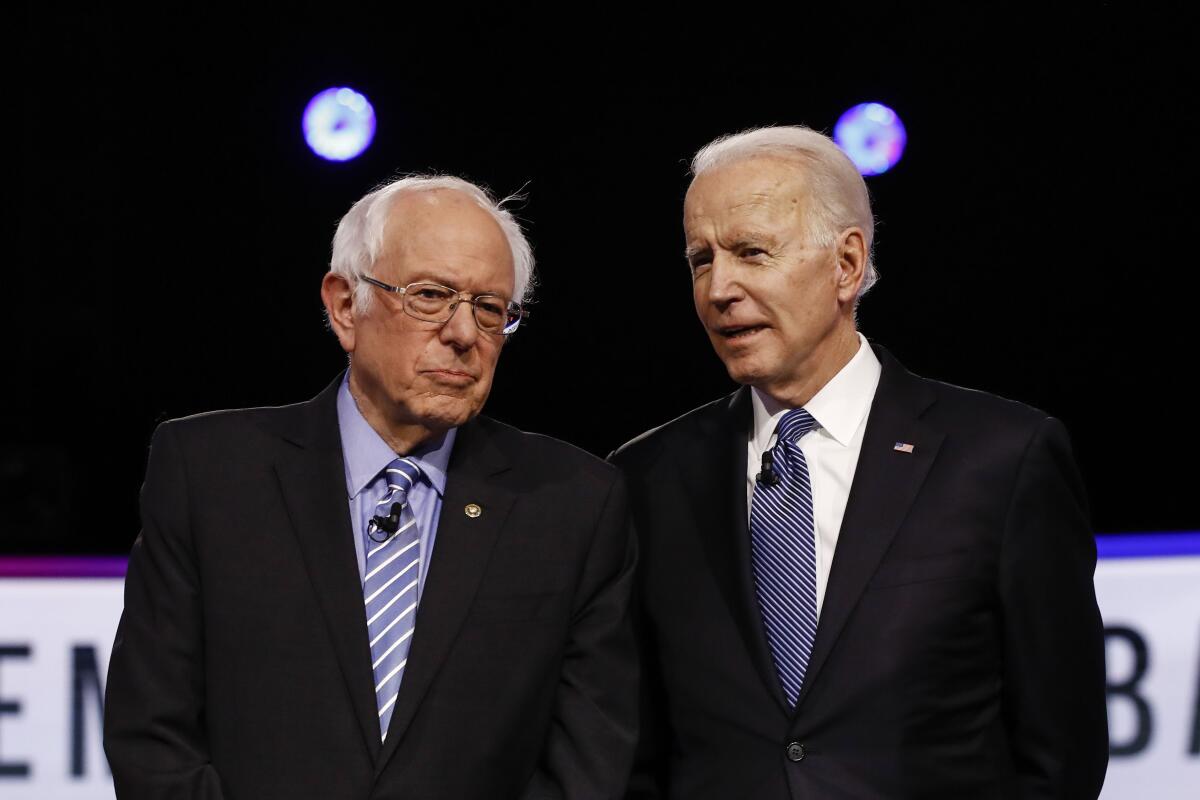

WASHINGTON — Less than a week after Sen. Bernie Sanders dropped his bid for the Democratic nomination, he endorsed Joe Biden for the presidency.

Americans needed to rally behind Biden, the liberal senator said, “to make certain we defeat someone I believe is the most dangerous president in the modern history of this country.”

That uneasy alliance of Democratic progressives and moderates helped Biden defeat President Trump despite attacks from Republicans that labeled the former vice president and his political allies as a “socialists.” But it didn’t take long for the progressive-moderate entente to crack under the pressure of deciding who gets cabinet roles and who is to blame for the party’s down-ballot defeats.

There’s no state that understands this dispute and all its complexities better than blue-to-the-bone California, where Democrats have controlled the legislature for more than two decades and the governor’s office since 2011. The state party is rife with serious disagreements and contested primaries.

“The joke in California politics is that this is a two party state — it’s just that they’re both Democratic parties,” said Dan Schnur, who teaches political communications at USC and UC Berkeley.

Sure, direct lessons are limited: state Democrats have some wiggle room because, as Schnur puts it, “there aren’t that many Republicans left to beat.” But California’s star is rising and a growing Democratic delegation that includes Kamala Harris as vice president is bringing their politics to Washington.

In the weeks since the election, I called a few experts who track California’s political landscape to discuss the ramifications of disputes within the Democratic party. Here’s how they see things.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

There are two parties, but no binary choices.

While most voters define themselves in relationship to Republicans and Democrats, the labels can obscure individuals’ policy preferences.

“Both Democrats and Republicans,” Schnur said, “end up with much bigger tents than their members would prefer.”

It’s no wonder, then, that Democrats — or any party — would experience internal disagreement.

Ben Tulchin, a San Francisco-based Democratic pollster and strategist who worked for Sanders, noted that one of the defining trends of the last decade was the rise of the populist approach, and populism isn’t partisan. President Trump and Sanders both speak to some of the same types of voters, those who feel the powerful aren’t listening to them.

“It’s not left versus right or left-center versus left in the party,” he said. “It’s the noise you hear, and I think that misses the mark.”

Tulchin points to the Vermont senator’s popularity in California. The strategy in appealing to voters was not ideological. Tulchin said Sanders pushed an economic message that spoke to specific anxieties, and the campaign ended up connecting with the right coalitions of local voters.

If there was a year for tensions to come to a head, it’s 2020.

History shows the two major parties have evolved in different ways, for different reasons, over the course of decades.

“On the Republican side, the most ideological people got control of the party years ago. They marginalized the old moderate wing,” said Raphael J. Sonenshein, a local government expert who runs the Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute of Public Affairs at Cal State L.A. “On the Democratic side, the left was always a step behind.”

A combination of historical factors and recent trends have positioned Democrats for what Sonenshein calls a “transitional period” into a new era — one with new voices and calibrated for different landscape.

The last decade has seen the party grow younger and more diverse. People of color are becoming important voices through activist movements. And populist messaging from candidates like Sanders and his allies are energizing voters. It’s all fuel for a progressive coalition to grow from the ground up.

While local political ecosystems, like deep blue L.A., have had time to adapt, Sonenshein says the national Democratic party is only just beginning to reckon with these new pressures. Throw in mixed election results — Biden’s success and the loss of House seats — and it’s a tinderbox.

“This very murky outcome has left them very frustrated and their natural instinct is to blame each other,” Schnur said.

Cohesion gets things done, but it rarely looks like one “side” winning.

In the weeks since his victory, Biden has stood in the center of it all. He ran on a platform of compromise and reconciliation. In his first cabinet nominations, he’s taken a “goldilocks” approach, offering largely uncontroversial picks. And that may be where a path forward lies.

“I heard a very good description about Biden, which is that he is adept enough to place himself in the center of wherever the Democratic party is, and that’s something the party has needed for a while,” Sonenshein said. “California politicians have been doing that for years.”

Schnur points to former California Gov. Jerry Brown, who was able to calm intraparty tensions with clear leadership. “There wasn’t space for either faction to gain much at the expense of the other,” he said.

But everyone I spoke to saw change ahead. Without Brown or another strong center of gravity, Schnur said, there’s deepening tension in California politics. He sees polarization that poses new challenges, ones that affect every level.

“To some degree, the post-Trump dynamic is similar to what’s happened at the state level,” he said. “It’s a lot of pent-up emotion.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest on the transition

— Tuesday was Safe Harbor Day — the federal deadline for states to resolve election disputes and certify their results. Read Matt Pearce’s story from October on how the deadline works.

— Without comment or dissent, the Supreme Court turned away the first appeal from Trump supporters to reach the high court, a claim by several Pennsylvania Republicans who said the state’s election results should not be certified. It may be the last appeal as well, reports David G. Savage.

— Biden will nominate retired four-star Army Gen. Lloyd J. Austin to be secretary of Defense, according to four people familiar with the decision. He would be the first Black leader of the Pentagon, but his nomination also drew criticism from lawmakers in both major parties who voiced concern or outright opposition to putting a career officer in a job usually reserved for a civilian, write David S. Cloud and Eli Stokols.

— Biden also formally introduced his health team, including California’s Xavier Becerra for secretary of Health and Human Services. Del Quentin Wilber and Patrick McGreevy have five things to know about him.

The view from Washington

— Even as President Trump claims credit for the rapid development of vaccines against the coronavirus, Noam N. Levey and Chris Megerian report that it remains unclear whether he will take the vaccine and how hard he’ll work to persuade skeptical followers to get immunized. And then there’s the fact that his administration chose not to lock in a second batch of doses.

— What might a Trump Presidential Library look like? It’s a matter of speculation and joking on social media, but someone took it seriously enough to give their vision a website. Times culture columnist Carolina Miranda interviews the anonymous creator.

— The House on Tuesday easily approved a wide-ranging defense policy bill by a veto-proof margin, defying President Trump.

The view from California

— The new two-year session of the California Legislature began Monday as legislators took the oath of office under some of the most unusual circumstances in state history, John Myers writes. They quickly compiled an urgent to-do list.

— Myers also writes that Gov. Gavin Newsom’s upcoming state budget will assume California’s tax windfall is $15.5 billion. Newsom shared the information at an event held by a technology industry trade group. (In case you missed it: here is Myers’ newsletter from Nov. 23 on why there’s a windfall at all.)

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.