Essential Politics: One year into COVID, Biden’s relief bill takes aim at pandemic damage and division

- Share via

WASHINGTON — This is the March 5, 2021, edition of the Essential Politics newsletter. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox three times a week.

On March 5, 2020, with only three dissenting votes, Congress passed the first COVID-19 relief bill, an $8.3-billion emergency measure that turned out to be the opening installment in a vast and expensive effort to deal with the costs of a deadly pandemic.

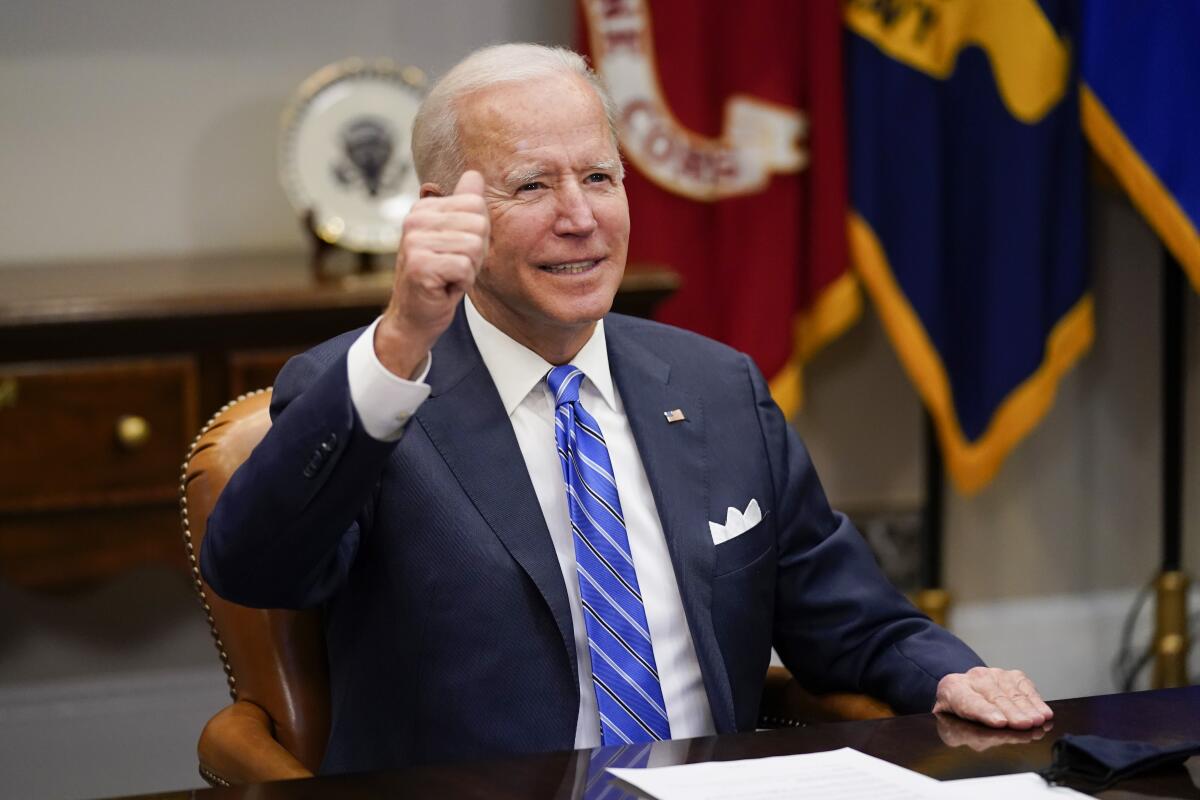

A year later, the Senate is nearing passage of a $1.9-trillion package proposed by President Biden. The political environment has changed. The bill passed the House last week on a near-party line vote of 219-212, with two Democrats and all the Republicans in opposition. It passed a key hurdle in the Senate on Thursday with Vice President Kamala Harris breaking a tie.

A year ago, when the U.S. death toll stood at less than a dozen, some believed the threat from a novel virus would cause the nation to pull together. More than half a million deaths later, we’ve learned otherwise: The pandemic deepened the nation’s divisions, mostly along partisan lines, even as it shined a harsh light on inequities of race, ethnicity and income that have played a huge role in who lived and who died, who lost a job and who did not.

“No country was as politically divided over its government’s handling of the outbreak as the U.S.,” the nonpartisan Pew Research Center discovered last summer in a 14-nation survey of public opinion. In some respects, U.S. divisions have grown even starker, Pew finds in a large-scale new study released Friday.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Biden’s hope is that the rapid ramp-up of vaccinations — the U.S. hit 2 million COVID shots a day on Wednesday — combined with passage of the relief package will begin to return the country to normal, repairing both the physical and economic ravages the virus has caused.

Beyond that, he has a broader and more challenging goal: Just as COVID worsened the nation’s divisions, he believes that resolving the pandemic can begin to narrow them.

Division amid optimism

Right now, that seems a tall order. Several recent surveys have shown the public growing more optimistic that the worst of the pandemic is behind us — Gallup reported Friday that for the first time, a majority of Americans now perceive the COVID situation as getting better. But the good news has generated new arguments.

On Tuesday, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves announced they were ending mask mandates in their states, despite public health advice to the contrary.

Biden the next day called those decisions examples of “Neanderthal thinking.”

The warring words reflected how much the partisan divide continues to shape the country’s response.

From the earliest weeks of the outbreak, Republicans were far less concerned about COVID than Democrats, Pew’s data shows. That gap grew steadily through last spring, fanned by President Trump, but also driven by the deeply ingrained skepticism toward government, disdain for experts and opposition to economic restrictions that characterize American conservatism.

Those same attitudes can now be seen when surveys ask about vaccination.

The share of Americans who say they likely will get a shot continues to rise, with hesitancy rapidly melting among some groups, especially Black adults, who initially had deep skepticism. The partisan gap, however, has grown — 83% of Democrats, but only 56% of Republicans, say they either have already gotten vaccinated or intend to, Pew found. Their poll surveyed 10,121 U.S. adults from Feb. 16 to 21 and has a margin of error of 1.6 percentage points in either direction.

Biden hopes passage of his COVID plan can narrow the political divides even as it assuages the economic pain of the last year.

The economic part is clear: Although many economists question some aspects of the bill, especially the amount it would send to state and local governments, there’s no question that the $1.9-trillion package would aim a firehose of money at the lower- and middle-income families that have disproportionately been burned by the pandemic.

Pew’s numbers illustrate how unequal the damage has been.

Upper-income Americans — which Pew defines as those with incomes above around $140,000 a year — are about four times as likely to say their family finances have actually improved in the past year as to say they have gotten worse, Pew found. That’s largely because most better-off Americans have kept their jobs and, with restaurants, theaters and travel shut down, haven’t had as much to spend their money on.

The vast majority of upper-income Americans said they had saved at least as much in the last year as they typically do, with nearly a third saying they added more to their savings than usual.

By contrast, among low-income Americans — those with incomes less than around $45,000 — roughly one-third say they are worse off now than they were a year ago. Only one in five say their family incomes have improved. The rest say their situation has remained about the same.

More than four in 10 Americans say they or someone in their household lost a job or income since the pandemic hit. Among low-income households, that rises to half. Among those who took a pay cut during the pandemic, about half report they are still earning less than before.

The relief bill includes $1,400 direct checks; extended unemployment compensation; enhanced assistance to families with children; an expansion of the earned income tax credit, which supplements wages for low-income workers; aid in paying rent; and a 15% increase in food stamp benefits. In all, hundreds of billions of dollars will go to families.

Republicans say that, with the economy already improving, that’s a lot more money than is needed. Some warn the flood of new spending will generate inflation. Biden and his economic advisors discount those fears. There’s a lot of room to rev the economy without worrying about overheating, they argue.

Beyond the immediate aid, though, the president has a larger ambition, which he touched on during remarks to House Democrats at a meeting Wednesday evening.

“The confidence in the American — in the American government has been plummeting since the late ’60s to what it is now,” he told them.

Passing the relief bill, he said, will “show the American people we’re capable of coming together for what matters most to them. They’ve lost faith in government; this is a time to reestablish that faith.”

“I think that people’s memories will be long,” Biden said. Proving that government was able to help when people needed help “is going to open up a lot of hearts and a lot of doors for us tomorrow to do the many more things we know we have to do.”

During the lowest points of his primary campaign last year, when Biden’s bid for the presidency seemed doomed, such sentiments from him drew mockery. It’s an audacious hope that still flies against much current wisdom about American politics. Then, again, so did his election.

The latest from California

In San Francisco, the guessing game has begun, writes Mark Z. Barabak: After Nancy Pelosi, who? The House speaker has indicated this could be her last term, and, given how rarely the occupant of that congressional seat comes open, the line of ambitious Democrats who would like the job is a long one.

In Sacramento, the Legislature gave final approval to a new plan to open the state’s schools. The $6.6-billion measure was a compromise that reflected the vastly disparate needs of different districts across the state, but left many worried they wouldn’t get enough help, John Myers and Taryn Luna wrote.

The lengthy debate over getting schools reopened is one issue that has helped fuel the effort to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom. As George Skelton wrote, a new poll in Orange County shows trouble for the recall effort.

In the nation’s two biggest Democratic states, the political story right now is governors in trouble, albeit for very different reasons. Evan Halper and Seema Mehta examined Newsom and New York’s Gov. Andrew Cuomo as they look for paths to political survival.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest from Washington

As Republican states try to pass new laws to restrict voting, the House passed a landmark election bill designed to expand it. As I wrote, the vote marked an intensifying battle over voting rights that is likely to play a big part in political debate this year.

“Infrastructure week” became a punchline in the Trump administration, which repeatedly talked about offering a bipartisan proposal to rebuild roads, bridges and highways, but never did it. For all the political attractiveness of the issue, getting a bill passed isn’t so easy. Eli Stokols looked at the question: Can Biden actually get infrastructure done?

Biden hopes to use infrastructure improvements to fight climate change. There are a lot of ideas being tossed around for innovative technologies that could reduce carbon dioxide emissions. But in some cases, there’s a lot more hope than science behind the proposals. Evan Halper examined one such idea, carbon banking, which could be a strike against global warming or maybe just a giveaway to Big Ag.

Noah Bierman examined how Harris has become a magnet for progressive pressure on the White House.

The Republican Party’s biggest problem is spelled T-R-U-M-P, writes Doyle McManus in his look at the state of the GOP’s divisions.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett issued her first ruling for the Supreme Court this week. As David Savage wrote, the 7-2 decision came in a case interpreting the Freedom of Information Act.

The head of the District of Columbia National Guard testified that he was “stunned” that he had to wait hours to dispatch troops on Jan. 6 as rioters stormed the Capitol. As Del Wilber wrote, his statement came in a hearing as Congress continues to look at the security failures that allowed rioters to take over much of the building.

Cabinet nominees (mostly) advance

Biden lost his first Cabinet nominee Tuesday as the White House bowed to the inevitable and withdrew Neera Tanden‘s bid to head the Office of Management and Budget, Jennifer Haberkorn and Eli Stokols wrote.

Since President Reagan, every new administration has lost at least one confirmation fight, and whether by design or happenstance, Tanden’s nomination has served as something of a heat shield for other Biden choices.

On Wednesday, Xavier Becerra’s nomination as Health and Human Services secretary moved forward to the Senate floor. As Sarah Wire wrote, he seems on track to win approval, although that may require Harris to break another Senate tie.

Also this week, the Senate confirmed Cecilia Rouse to head the White House Council of Economic Advisors, Gina Raimondo as secretary of Commerce and Miguel Cardona as secretary of Education.

Several nominees have cleared Senate committees and are now set for a final vote, including Merrick Garland to be attorney general. Biden’s pick for Interior secretary, Rep. Deb Haaland of New Mexico, also won committee approval, picking up the backing of Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), which put her on track for confirmation.

Stay in touch

Send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com. If you like this newsletter, tell your friends to sign up.

Until next time, keep track of all the developments in national politics and the Trump administration on our Politics page and on Twitter at @latimespolitics.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.