Astros’ feeble news conference is followed by seemingly sincere apologies by players

- Share via

WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. — Baseball demanded a pound of flesh from the Houston Astros, who for months showed little remorse for a sign-stealing scandal that rocked the sport and tainted their 2017 World Series win over the Dodgers.

It finally got one — or, at least, a chunk of one — on a warm, breezy Thursday morning on Florida’s East Coast, but even that took longer than it should have.

Only two players spoke at a news conference televised live by MLB Network, and third baseman Alex Bregman’s 40-second apology and second baseman Jose Altuve’s 30-second apology probably did little to appease players who are furious with the Astros’ cheating and lack of accountability.

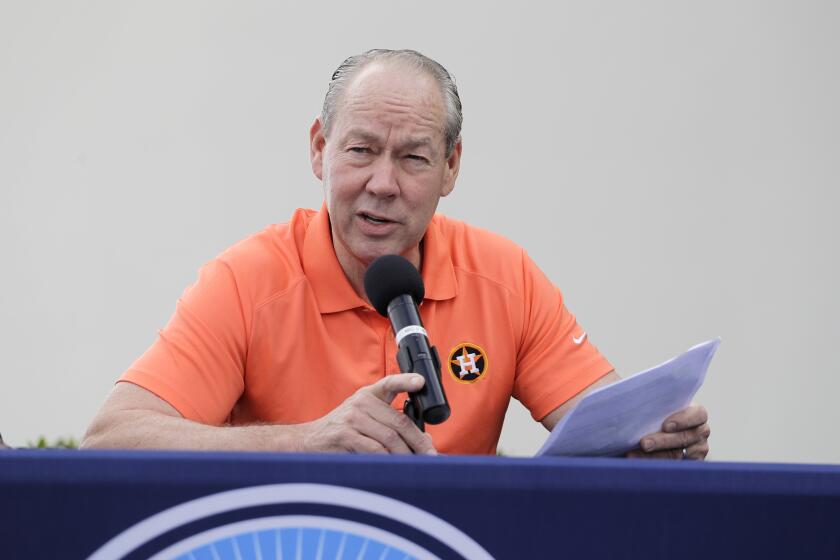

And owner Jim Crane’s contention that Houston’s theft of signs “didn’t impact the game” only inflamed the anger of fans and insulted the intelligence of players from teams the Astros vanquished in the 2017 postseason — the Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees and Dodgers.

But when the formal proceedings before about 100 media members and 15 camera crews broke up, a more authentic attempt at contrition began.

Waiting for reporters in the team’s spring training clubhouse were all six remaining position players from that 2017 team — Altuve, Bregman, shortstop Carlos Correa, first baseman Yuli Gurriel and outfielders George Springer and Josh Reddick — as well as ace pitcher Justin Verlander.

Each stood at his locker and answered questions for 30-40 minutes in what amounted to a group mea culpa the Astros hope will start the process of regaining the trust of opposing players and fans.

“I don’t want my kids, I don’t want my brother, I don’t want my family members or people who follow me to think that it was right to cheat to be successful,” Correa said. “What we did in 2017 was terrible. It was straight-up wrong. We all know it and feel really bad about it.”

Players would not discuss specific details of their high-tech scheme, which came to light publicly in November when the Athletic published a story in which former Houston pitcher Mike Fiers’ alleged that the 2017 team used electronic equipment to steal signs during games, a violation of baseball rules.

Astros owner Jim Crane came across as an out-of-touch plutocrat used to people telling him they agree with whatever nonsense comes out of his mouth.

A Major League Baseball investigation determined that throughout the 2017 season and for part of 2018, video room staffers used a center-field camera to steal signs from the catcher.

Those signs were relayed to the batter in real time by whistling, clapping, yelling and eventually banging on a trash can at the base of the dugout steps — one or two bangs for certain off-speed pitches and no bangs for a fastball.

The commissioner’s Jan. 13 report stated the trash-can banging was in place throughout the postseason in 2017, when the Astros went 8-1 at home, but not in 2018 or 2019.

Players adamantly denied they wore devices or buzzers under their uniforms to electronically transmit information in 2019, a season that ended with a seven-game World Series loss to the Washington Nationals.

“It’s an unfair advantage, I’m not going to lie to you,” Correa said of the 2017 scheme. “When you know what’s coming, I think you have a slight edge. … But it stopped. It didn’t happen at all in 2018, it didn’t happen at all in 2019, and it’s not going to happen at all moving forward.”

That’s of little consolation to the Dodgers and especially Clayton Kershaw, who coughed up leads of four runs and three runs in a wild 13-12 World Series Game 5 loss in Minute Maid Park.

If the Dodgers won that game and a series the Astros went on to win in seven games, perhaps Kershaw’s legacy — that of a once-in-a-generation ace who struggles in October — would be different.

Dodgers pitchers and catchers reported to spring training, so manager Dave Roberts was too busy to worry about the Astros’ apologies for stealing signs.

Reddick was a teammate of Kershaw and the rest of the Dodgers for the final two months of 2016 but said he didn’t feel a need to reach out to him or any other Dodgers to apologize.

“That would definitely be a difficult conversation for me,” Reddick said. “It is what it is. We have to ask for forgiveness and say how bad we feel about not taking a bigger role in preventing it.”

Was Reddick remorseful because the Astros got caught or because he knew what they were doing was wrong?

“No, I think it was definitely more knowing it was wrong and not stepping in and putting an end to it,” Reddick said, “because we did break the rules.”

Correa said the sign-stealing system was more difficult to use in the 2017 playoffs.

“The regular season is when we used it the most,” Correa said. “When it comes to the playoffs, it’s loud, people were using multiple signs at the stadium because of rumors of what was going on at the time.

“When I look back at the playoffs and look back at the game, it was not as effective as the regular season. The trash can was there, yeah. But I remember them using multiple signs and it was impossible to decode all of them.”

Opposing players have heaped scorn upon the Astros. Philadelphia reliever David Robertson said, “It’s a disgrace what they’ve done.” Cincinnati pitcher Trevor Bauer, writing in the Player’s Tribune, said Houston’s sign-stealing scheme is “up there with the Black Sox scandal and will be talked about more than steroids.”

When the Houston Astros present themselves publicly, they will not do so as AL champions. They will do so as baseball’s greatest villains of this generation.

Angels pitcher Andrew Heaney torched the Astros, saying that “for nobody to stand up and say, ‘We’re cheating other players,’ that sucks. That’s a [bad] feeling for everybody. I hope they feel like [crap].”

Major leaguers are part of a fraternity. They form one of the most powerful unions in professional sports. Now, those bonds are broken.

“There is a thing in this game that we can all hold our hat on, and the respect of your peers is one of the biggest,” Springer said. “For guys who are upset, I understand. You don’t ever want to be in this situation.”

Cleveland Indians ace Mike Clevinger expects some pitchers to exact revenge on the Astros with some strategically placed fastballs this season.

“I don’t think it’s going to be a comfortable few at-bats for a lot of those boys, and it shouldn’t be,” Clevinger said last month. “They shouldn’t be comfortable.”

Verlander, a 15-year veteran and two-time Cy Young Award winner armed with a 95-mph fastball of his own, hopes it doesn’t come to that.

“Look, when we step away from the field, we have families — I have a little girl, Jose has kids — it’s different when you bring health into the equation,” Verlander said. “I think the commissioner has made it clear that a baseball thrown at a player is not an appropriate form of retribution.”

Fans will be hurling insults and booing loudly in opposing ballparks. The Astros are braced for it.

“As a team, we’re ready for anything, man,” Correa said. “We know we were wrong so have to be responsible for what we did. It’s not going to be a fun season on the road. But at the same time, we have to stay focused and try to play baseball. Moving forward, we want to show everybody that we’re talented and we can play the game.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.