What’s in a sports nickname? A lot. Take the Los Angeles Lakers ...

- Share via

Let’s play a little word association.

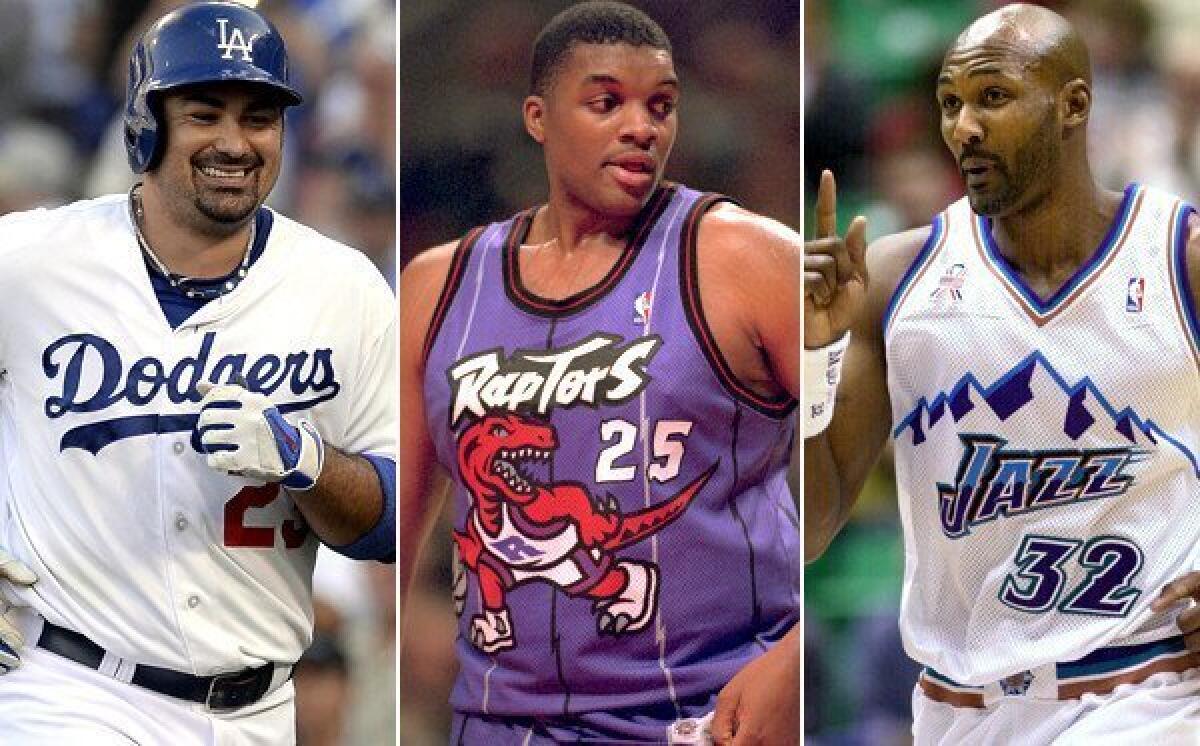

If you hear “jazz,” what’s the first thing that pops into your mind? Utah, right? Because nothing says “Dixieland” like the Beehive State.

Or how about velociraptor, the dinosaur made famous in the movie “Jurassic Park”? Makes you think of Toronto, doesn’t it?

And what conjures thoughts of a cool mountain lake better then a desert? So it makes perfect sense that the first NBA team to play in Los Angeles should be called the Lakers.

Well, not exactly.

But there are reasons why those names remain. The Jazz kept its nickname when it moved from New Orleans to Salt Lake City because the club still had plenty of leftover merchandise to sell. Toronto thought — incorrectly, as it turned out — that the locals would associate with a Raptor because part of “Jurassic Park” was filmed there. And the Lakers just didn’t bother to change the name when departing Minnesota, “The Land of 10,000 Lakes,” for arid Southern California.

So while the names Jazz, Raptors and Lakers might not fit their cities, they fit nicely on a T-shirt. And in the marketing-mad world of professional sports, that’s really all that matters.

“It’s a part of our enthusiasm. The nickname becomes part of being involved,” says John Rowady, president of the Chicago-based sports marketing firm rEvolution. “So nicknames are really important to associate with what it means to be that fan.”

Market strategist Harvey Chimoff agrees.

“It helps with the branding,” he says of nicknames. “If you think in terms of any favorite product, regardless of the product category, there’s some connection that we, as consumers, have with it. For sports teams the nickname has become sort of the shorthand connector between the fans and the team.”

In some cases the connection is so strong that the city it represents becomes insignificant.

When the Dodgers left Brooklyn for Los Angeles, team historian Mark Langill said, the nickname was considered so iconic that there was no thought of changing it.

The name was as Brooklyn as the bridge, inspired by a pejorative Manhattanites once used for residents of a borough so packed with trolley lines that people literally became “trolley dodgers.” But a new name? Fuhgeddaboudit!

“It was just always going to be Dodgers,” Langill says. “The only thing they had to do was change the initials on the cap.”

Other municipalities have argued nicknames are community property. When the Browns announced they were leaving Cleveland in 1996, the city took the team to court and forced it to relinquish the intellectual property rights and history associated with the name. As a result, the team became the Ravens when it moved to Baltimore. When the NFL returned to Cleveland three seasons later, the new ownership assumed the Browns’ name, colors and record book.

A dozen years later Seattle followed suit, taking the owners of the NBA’s SuperSonics to federal court ahead of the franchise’s 2008 move to Oklahoma City. Seattle wound up with the rights to the Sonics’ name and logo, forcing the franchise to come up with a new moniker, the Thunder.

The NFL’s Colts, on the other hand, kept their name, uniform and distinctive horseshoe logo when they sneaked out of Baltimore for Indianapolis in 1984, just as the Rams took their name with them from Cleveland to Los Angeles to St. Louis, and baseball’s Braves played under the same name and logo in Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta.

Not all nicknames are as portable. When the Houston Oilers decamped for Tennessee in 1997, the team kept the nickname for two seasons before acknowledging Nashville had nothing to do with oil. The team renamed itself the Titans.

Though nicknames have become so valuable that judges are determining their custody, there was a time when teams had no nicknames at all.

“The formal names of the clubs, as they were incorporated, tended to be very bland. And the nicknames were not added until the 20th century in many cases,” says John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian.

Those early nicknames were inspired most often by the color of a team’s uniform. The Reds, baseball’s oldest nickname, comes from the color of the socks the players wore; the team originally was known as the Cincinnati Red Stockings and, for a few years during the anti-communist “Red Scare” of the 1950s, as the Redlegs. The Chicago White Sox, the St. Louis Browns and the Boston Red Sox also were named for hosiery.

Other nicknames were coined by sports journalists, who were either looking for more colorful names or for shorter ones that would fit into headlines.

It was an editor with the Chicago Daily News who was credited with first calling Chicago’s National League team the Cubs because it had a number of young players. The frustrated editor of a New York paper, unable to fit Hilltoppers and Highlanders into headlines, reputedly began calling the city’s American League team the Yankees. The name quickly caught on with journalists, who used it so often it was eventually adopted by fans.

“Baseball was so dominant a sport in America between 1900 and 1920 that writers were coming up with endless nicknames for the clubs,” Thorn says. “You cannot overemphasize the need to contract ballclub names for headline purposes.”

Aside from making jobs easier for copy editors, in their earliest days nicknames were also meant to connote an attitude or spirit, as when Times sportswriter Owen R. Bird likened members of USC’s track team to Trojans. That was 1912 and USC has been the Trojans since.

Animal nicknames have been popular too, dating to the first collegiate competitions involving such venerable schools as Columbia, Princeton and Brown — known, respectively, as the Lions, the Tigers and Bears . . . oh my!

Soon so many animals were running amok that the herds needed to be thinned. So when Canoga Park High in the San Fernando Valley chose its nickname, a student named Robert Parks took stock of the school’s rivals — the Van Nuys Wolves, North Hollywood Huskies and San Fernando Tigers — and suggested the Hunters. Nearly nine decades later, a woodsman with a rifle and a coonskin cap remains the school’s logo.

“When a lot of nicknames were created, they were created about the battle, the fight,” Rowady says. “Those were fighting, warring types of names that brought fear as we entered into the arenas to go to battle.”

Some nicknames are chosen or retained for economic reasons. The Jazz kept the nickname and colors — green, purple and gold, the colors of Mardi Gras — after the move to Salt Lake City because the franchise was awash in unsold bumper stickers, T-shirts and jerseys with the name and logo on them. The team has changed color combinations and uniform styles many times since, but never changed the name.

When Disney joined the NHL in 1993, the name for the Anaheim expansion team — Mighty Ducks — was little more than a marketing tool for its trilogy of hockey-themed movies. Early on the movie tie-in helped the team lead the NHL in merchandise sales, but that popularity waned and a year after Disney sold the franchise the “Mighty” was dropped.

Not all nicknames have such simple, agreed-upon etymologies. Take the NFL’s Buffalo Bills, whose name is widely thought to have been inspired by Wild West showman Buffalo Bill Cody but actually comes from the name of a male bison. And contrary to numerous claims, Barron Hilton did not name his new American Football League team the Los Angeles Chargers as a cheap plug for a charge card he was marketing.

“It was after the trumpet call, followed by the roar of ‘Charge,’” Hilton, who moved the team to San Diego in 1961 after one season in L.A., often said. “It never had a thing to do with the credit card.”

Then there’s Walter Brown, the first owner of the Boston Celtics, who personally chose that now-iconic nickname over Unicorns and Whirlwinds, names his persistent public relations staff preferred for his basketball team. Brown was reportedly inspired by a barnstorming team from New York that had called itself the Celtics a generation earlier. And besides, Brown said, “Boston is full of Irishmen.”

The Heat nearly entered the NBA as the Miami Beaches, and before San Jose’s NHL expansion team became the Sharks in 1991, nicknames under consideration included Salty Dogs, Screaming Squids and Rubber Puckies.

Very punny.

But that’s not all. If saner voices hadn’t prevailed, the New York Mets would be the Skyliners and the Raiders would be the Oakland Señors. And the only thing that stopped the Dallas Cowboys from starting life as the Steers was president/general manager Tex Schramm’s worry that a castrated mascot would lead to ridicule in the testosterone-addled NFL.

Others took a higher road. When Jack Kent Cooke brought hockey to Los Angeles, he wanted to give his team an air of royalty. So he named it the Kings, put a crown on their sweaters and outfitted his players in gold and purple, the latter color one Queen Elizabeth I reserved for members of the ruling family.

It would be 44 years — and a number of uniform changes — before the team would rule the NHL. But the regal bearing Cooke had sought has become such a part of the Kings’ DNA that the team’s top minor league affiliate is the Manchester (N.H.) Monarchs.

If only every nickname was as easily understood.

“I wish somebody would complain [about] the Indiana Hoosiers name,” Rowady says of the Big Ten power. “That’s where I went to school and I still can’t tell people what a Hoosier is.”

Twitter: @kbaxter11

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.