Behind the story: Getting a look at baseball’s future while exploring its past

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — So you think you know baseball?

The Dodgers and Angels combined to sell more than 7 million tickets last year. Some fans come simply to root for the home team, to enjoy a day with the family, to wolf down one too many Dodger dogs. The casual fans might come to collect a bobblehead doll of Cody Bellinger, the best player on the Dodgers. The die-hard fans know all the players, even the obscure ones, and the even more obscure candidates to replace them.

I thought of those die-hard fans when the Society for American Baseball Research, or SABR, announced its annual convention was headed to San Diego this year, a gathering of what the organization billed as “the most passionate and knowledgeable baseball fans in the world.” The trivia contest there would be a glorious jumble of passion and obscurity, and there could be a rollicking story to tell about the contestants and their devotion to random and inconsequential facts.

Each year the Society for American Baseball Research holds a contest that’s part bar exam, part National Spelling Bee.

I hope you enjoy that story. But, as I entered the hotel ballroom for the competition, I looked around and found another story staring me in the face. The faces staring back at me were predominantly white, male and old.

This is the demographic challenge faced not only by SABR but by the game of baseball itself. From the day he became the major league commissioner in 2015, Rob Manfred has directed resources toward this challenge. He is well aware that the most reliable predictor of whether someone might become a lifetime fan is whether he or she played the sport as a child.

Manfred has established ties with youth baseball organizations, staged an annual major league game at the Little League World Series, and accelerated the growth of academies throughout the United States. He also pushed the “Fun at Bat” baseball-themed play program in the continental U.S., Puerto Rico, Mexico and the United Kingdom.

Try answering some of the questions posed in the annual trivia contest held by the Society for American Baseball Research.

But getting kids out to the ballgame might not win them over, not when the pace of play is plodding and a hand-held phone offers a blizzard of options that cater to a short attention span. I wondered whether the embrace of trivia might help a sport that struggles to market itself.

What John Thorn, the league’s official historian, calls “nerd culture” has made baseball ruthlessly efficient, but far less aesthetic.

The thrill of the stolen base has vanished; risk management has all but eliminated the stolen base. Data have driven decisions that have turned a three-hour game from an unusually long event into a depressingly routine occasion.

The home run has been cheapened. Swing for the fences, everybody, and there is no shame in swinging and missing, over and over.

“I have described this as the paradox of progress in baseball,” Thorn said. “The game is better on the field. We also know that the strategies employed to attain victory are better than they have ever been. And yet somehow it feels worse.”

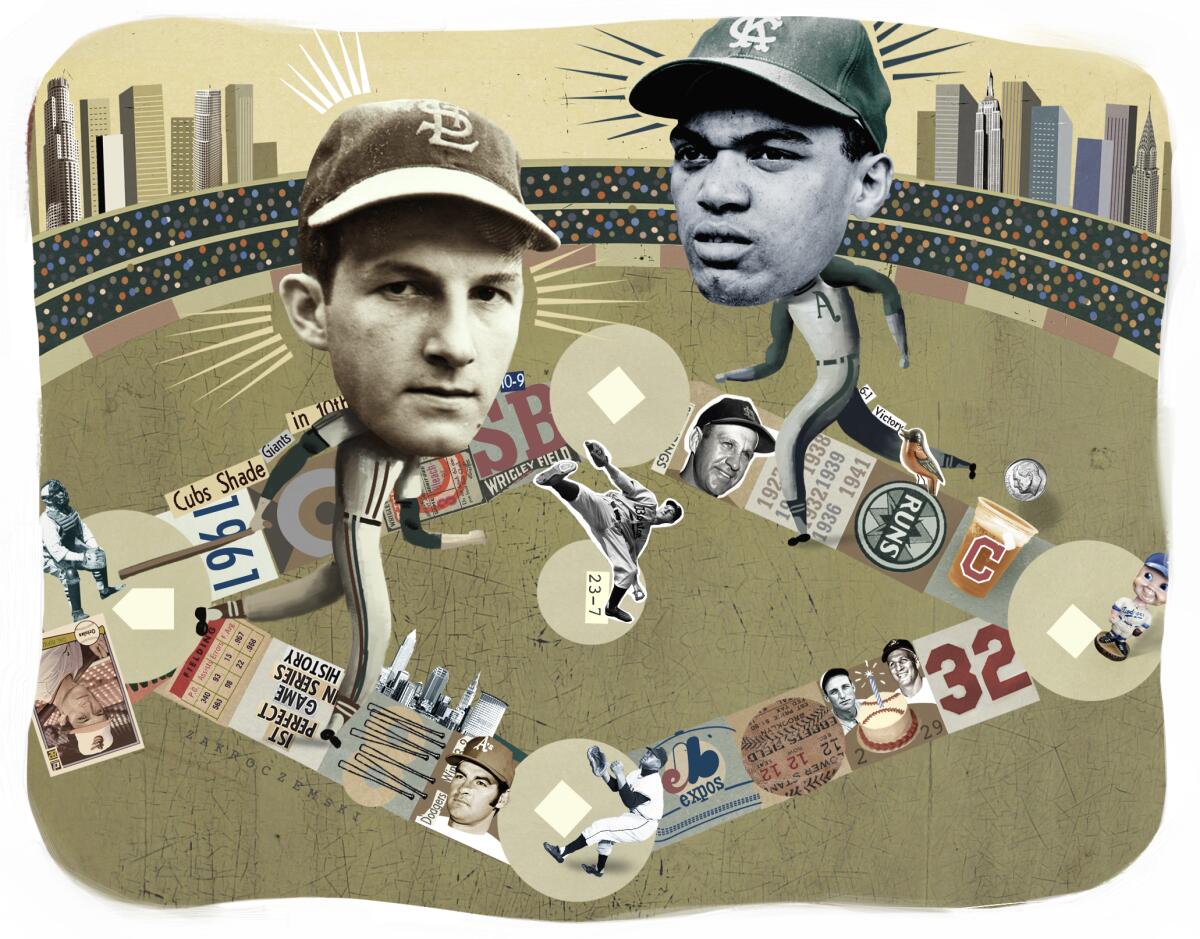

The cultural touchstones have all but disappeared. In an era when baseball was the unquestioned national pastime, even the most casual of sports fans knew the meaning of 714 (Babe Ruth’s career home run total) and .406 (Ted Williams’ batting average in 1941, as the last player to hit .400). It was easy to understand: a ball that sailed over the fence was a home run; batting average was calculated by dividing hits by at-bats.

Today, when baseball fights for attention, the statistics spawned by nerd culture can be almost incomprehensible to a potential fan. It is considered the gospel truth that the Angels’ Mike Trout is the best player in baseball; the evidence is a statistic called WAR.

The acronym stands for “wins above replacement.” The statistical sites that calculate it cannot agree on how to do so, and best of luck should you try. The method, according to the MLB website: Add four other statistics and divide by a fifth, but none of those statistics are simple.

“Stats are signposts to stories,” Thorn said. “Stories don’t vanish. We may not any longer be able to have a single signpost to a single story, but rather a series of signposts to a series of stories.”

There are signposts of history, and no sport celebrates its history better than baseball. Trivia celebrates history too, and stories. When fans invest in a player or a team, they invest in stories more than they do in statistics.

For all the initiatives Manfred considers to speed up the pace of a game, he might also find a way to popularize trivia to the masses that might care, say, less about the statistics compiled by Hall of Fame pitchers Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard, and more about their tale of spending winters performing on the vaudeville circuit. Marquard even got caught up in a scandalous love triangle.

“Trivia is not anathema to growth,” Thorn said. “It may well be a vehicle to growth, in which case I would applaud it.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.