From used-car lot to Dawg Pound: Freddie Kitchens’ grit and heart help revive Browns

- Share via

CLEVELAND — It didn’t last long, but the year before he got back into football, Cleveland Browns Coach Freddie Kitchens was a used-car salesman.

Such an odd fit for the plain-speaking Kitchens, a former Alabama quarterback, who has always been a people person but can’t get out of the way of his own candor.

“I like being straight up and honest with people,” said Kitchens, 44. “I’d tell people, ‘I wouldn’t buy this car for this much.’ But then you don’t make any money, so you’re kind of torn.”

Still, Kitchens was salesman of the month twice in his three months at Magnolia Nissan BMW in Tuscaloosa, Ala. He could move that inventory, even though he didn’t care for the job.

“I was just not happy,” he said, his thick Southern drawl softened a bit by NFL moves from Dallas to Arizona to Cleveland. “Just kind of living life.”

Twenty years later, after building a coaching career from the unglamorous ground floor and surviving a perilously close brush with death, Kitchens is trying to restore a once-classic NFL franchise. The Browns, who play host to the Rams on Sunday night, are studded with talent on both sides of the ball but still need to prove they can parlay that into victories.

They were embarrassed in their opener — a 43-13 loss at home to Tennessee — but came back in Week 2 with a 23-3 road win over the New York Jets. Now they face the 2-0 Rams, among the league’s hottest teams, in a game that pits a pair of quarterbacks selected No. 1 overall: Cleveland’s Baker Mayfield versus Jared Goff of the Rams.

With Tyler Higbee sidelined because of a bruised lung, Gerald Everett will start at tight end Sunday night against the Cleveland Browns.

This is one of four prime-time games for the Browns, who won four NFL championships yet haven’t won a playoff game since the 1994 season. The team’s hopes now hinge on an offense that includes the dynamic Mayfield and Odell Beckham Jr., perhaps the best receiver in the game, and a defense featuring vice-grip ends Myles Garrett, also a former No. 1 pick, and Olivier Vernon.

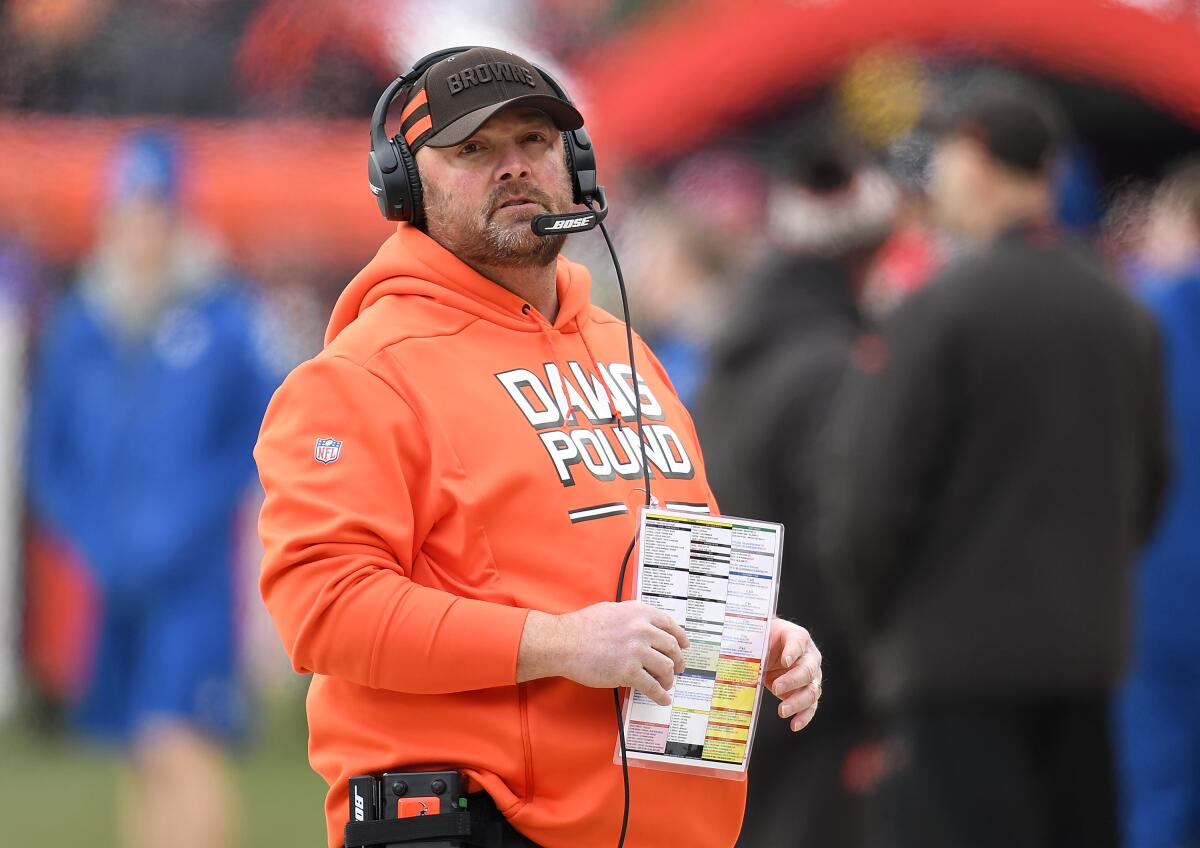

Overseeing it all is the folksy, beefy Kitchens, who’s refreshingly out of step with the buttoned-down, corporate NFL world. On the sideline, he wears an orange hoodie that reads “Dawg Pound,” making him look as if he stepped right out of the crowd and pulled on a headset.

At one point last season, after Kitchens had been promoted to interim coach, he pulled on Mayfield’s beard and teased him about it. When Kitchens walked away, the mic’d-up quarterback rolled his eyes, looked over at a teammate and said playfully, “That guy’s an idiot.”

“Freddie’s just a guy. He’s so easy to get along with whether you’re a CEO of a Fortune 500 company or a young kid at a local high school that he swings by to talk to,” said retired quarterback Carson Palmer, who had Kitchens as his position coach with the Arizona Cardinals. “He somehow finds a way to relate to everybody and anybody. He’s so easy to vent to. And then he always finds a way to hear you, listen to what you’re saying, but then kind of reel you back in.”

Unquestionably, Kitchens has perspective. Some of that came with the Cardinals in the summer of 2013, when he nearly died on the practice field. His aorta tore like an old garden hose left out in the sun too long. No one knew it at the time, and it wasn’t the kind of complete tear that would have meant sure and almost instant death. But it was a dire situation.

It was a Tuesday, and the Cardinals were staging a few spring practices before a mini-camp the following week. As soon as the horn sounded to begin the practice period, Kitchens sprinted out to his spot on the field to wait for his jogging players and hit them with his old line: “What took you so long?” This felt different.

“I did it that day, and as soon as I’m turning around I hear a pop,” he said. “And then my vision went white, like I was staring into the sun.”

He was essentially blinded, so much so that he couldn’t read Palmer’s number when the quarterback was standing 10 feet away.

“Goodness,” Kitchens gasped, “what does a heart attack feel like?”

His players immediately started giving him a hard time. They thought he might just be dehydrated on a warm but not sweltering day. They asked if he’d been out the night before, joked he might be hung over.

“I remember looking over and and telling him, ` Freddie, you’ve got some really bad rosacea,’” recalled former Arizona quarterback Drew Stanton, now the backup in Cleveland. “He’s like, `Yeah, my ro-AY-see-ah is really bad.’ He’s huffing and puffing.”

With the Chargers’ Adrian Phillips sidelined because of a broken arm, Roderic Teamer is set to make his NFL starting debut at safety against Houston.

They ran through some drills, and Kitchens’ condition was not improving. Pain radiated from his back down his leg to his foot, which eventually went numb.

“We’re jogging over to special teams and Freddie’s trying to jog and just looks like he’s in so much pain,” Stanton said. “By that point, the trainers are coming over. We were kind of laughing at first, but it did not look good from the onset. Then in true Freddie form, he’s trying to tough it out: `I’m good, let’s keep going.’”

Trainer Tom Reed knew something was very wrong, and it wasn’t just a case of dehydration. Kitchens didn’t want an ambulance called, so a Cardinals intern drove him to a nearby hospital. There Kitchens stayed for more than six hours before a CT scan revealed a tear within the wall of his aorta, just above the heart. Doctors say that most people who suffer that die suddenly from it.

Because there were no doctors at that hospital who could perform that surgery, and due to rush-hour traffic, Kitchens was airlifted 13 minutes by helicopter to the Abrazo Arizona Heart Hospital.

This has become part of Kitchens lore: He was so enthralled by the idea of riding in a helicopter, and so wanted his daughters to see what it was like, he spent the whole ride taking photos and videos out the window. He was filled with childlike wonder, even as medical personnel worried he might not survive the flight. When he landed at the second hospital, Kitchens could see the BMW of Coach Bruce Arians pulled into the parking lot.

As for his two daughters and wife, Ginger, they were on summer break in Virginia, and only learning of Kitchens’ health situation. Ginger immediately boarded a flight — leaving before the private jet arranged by Cardinals owner Michael Bidwill arrived — and was on her way to Arizona. She spent agonizing hours on that commercial flight not knowing whether her husband would be alive when she landed. It was a nightmare.

Dr. Andrew Goldstein performed the eight-hour surgery to repair the aorta and was struck by how calm and composed Kitchens was beforehand. As someone later pointed out to Goldstein, it was as if Kitchens were coaching him with a pep talk before the operation.

“He was kind of supernaturally relaxed and kind of matter-of-fact about it,” Goldstein recalled. “It wasn’t that he was telling me what to do, but he was like, ‘OK, man, let’s get this taken care of.’ It was unreal, especially because I heard in retrospect that [medical personnel at the first hospital] told him he was most likely not going to survive.”

Kitchens and Goldstein have become friends, and the doctor was there for the Browns’ opener this season.

“I bonded with the guy immediately because he’s such a unique individual,” Goldstein said. “I’ve never seen a guy who’s as tough and as kind, all at the same time. It’s just a remarkable blend.”

That’s something people saw when Kitchens was a quarterback at Alabama from 1993-97, where Arians was his offensive coordinator.

Chargers’ Scott Quessenberry was thrilled to discover his lineman brother, David Quessenberry, had caught a TD pass in Week 2 for the Titans.

“Tough as nails, one of the toughest kids I ever coached,” recalled Arians, now head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. “We were very average, or below average in the offensive line. He took a beating, but he never complained. He thought he was going to win every down.”

That grit resurfaced when Kitchens left used-car sales to take a ground-floor job coaching running backs and tight ends at Glenville (W.Va.) State College.

“I called the coach and he said, `I can’t pay you anything; I can give you $500 all at once, or $125 a month,” Kitchens recalled. “I said, `I’m going to need it all at once, and two days later I was up there.”

The place and the job were about as far from the spotlight as can be.

“I was washing laundry, picking up rocks on the field, pretty much everything,” he said. “That was Division II football, so we didn’t have a grounds crew.”

That led to jobs at LSU, North Texas, and Mississippi State, before he was hired to coach tight ends for the Cowboys in 2006 and his NFL career was underway.

“Freddie is one of those guys who would be successful at whatever he was trying to do — sell vacuum cleaners, a coach, a teacher,” Palmer said. “Whatever he would need to do, he would find a way to get it done. He could go into any field.”

That field is now in Cleveland and home to the win-starved Browns. New place. New challenge. Same belief.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.